Energy Blog: Electricity Not a Critical Import

Energy Blog: Electricity Not a Critical Import

The cross-border feuding between the U.S. and Canada raised the profile of North American energy flows.

The first two months of the second Trump Administration have not lacked for drama, especially with regard to tariffs. President Trump is particularly fond of those taxes on imported goods and has sought to levy them in response to a number of economic situations and policy disputes. Most notably, considering a free trade agreement that President Trump himself signed argues against this, the Trump Administration has announced (and then sometimes deferred) stiff tariffs on goods from Canada and Mexico.

The disparity in population and gross domestic product between the United States and the other two countries might suggest that this trade dispute would be an uneven fight, but Canada is looking for ways to inflict targeted pain. In addition to proposed counter-tariffs on Kentucky bourbon and sporting goods, energy has become a potential weapon.

On the one hand, many U.S. refineries are set up to process heavier Canadian crude oil. For instance, the BP refinery at Whiting, Ind., has been especially configured to handle heavy oil; according to reporting from the New York Times, between 65 and 75 percent of the oil it refines comes from Canada. Although the U.S. produces more oil than it consumes, the vagaries of refinery specialization see it exporting crude to South Korea and the Netherlands on the one hand while importing crude from Canada and Mexico on the other. Disruptions in the supply from Canada or Mexico may cause gasoline shortages even as the country continued to export oil.

Electricity has also been considered as a cudgel. The premier of Ontario (sort of a provincial governor) Doug Ford has threatened to impose a 25 percent surcharge on electricity exported to around 1.5 million homes in Minnesota, Michigan, and New York state. Some other Canadians have suggested shutting off electricity flow to the U.S. altogether.

While that sounds dire, the reality is more complex. Each of the Canadian provinces the border is connected to the U.S. market. In fact, aside from Quebec, the border provinces all participate in either the Western Interconnection or the Eastern Interconnection, the large networks of high-voltage AC transmission lines that help move electricity from market to market. (Quebec is connected to the New England and New York system operators via AC-to-DC-to-AC ties.)

Depending on the time of year or long-term climate variables, the flow of electricity might go in either direction. That’s due in large part to the large penetration of hydroelectricity in the Canadian grid; when there’s a drought, as there was in British Columbia and Quebec in 2024, those hydro plants can’t produce enough power for local customers, while in wetter years, the excess power is sent south. The swings can be wide. In the summer of 2022, Canada on net exported more than 4,000 GWh per month to the U.S. In the summer of 2024, the U.S. exported around 1,000 GWh per month to Canada.

To put those numbers into perspective, a 1 GW nuclear power plant running 24/7 would produce 720 GWh per month. So the net flow is about the same as adding a few large plants. While losing access to that electricity that might produce higher prices in some locations, especially in the short term, it wouldn’t have the effect of leaving Americans shivering in the dark.

To put those numbers into perspective, a 1 GW nuclear power plant running 24/7 would produce 720 GWh per month. So the net flow is about the same as adding a few large plants. While losing access to that electricity that might produce higher prices in some locations, especially in the short term, it wouldn’t have the effect of leaving Americans shivering in the dark.

That’s likely the bottom line for the trade war in its entirety. While the North American economies are so tightly bound that industrial supply chains often rely on multiple border crossings of components, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico are all large and diverse enough that losing access to a trade partner won’t cripple them. It will leave their consumers all a bit poorer, however.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

The disparity in population and gross domestic product between the United States and the other two countries might suggest that this trade dispute would be an uneven fight, but Canada is looking for ways to inflict targeted pain. In addition to proposed counter-tariffs on Kentucky bourbon and sporting goods, energy has become a potential weapon.

On the one hand, many U.S. refineries are set up to process heavier Canadian crude oil. For instance, the BP refinery at Whiting, Ind., has been especially configured to handle heavy oil; according to reporting from the New York Times, between 65 and 75 percent of the oil it refines comes from Canada. Although the U.S. produces more oil than it consumes, the vagaries of refinery specialization see it exporting crude to South Korea and the Netherlands on the one hand while importing crude from Canada and Mexico on the other. Disruptions in the supply from Canada or Mexico may cause gasoline shortages even as the country continued to export oil.

Electricity has also been considered as a cudgel. The premier of Ontario (sort of a provincial governor) Doug Ford has threatened to impose a 25 percent surcharge on electricity exported to around 1.5 million homes in Minnesota, Michigan, and New York state. Some other Canadians have suggested shutting off electricity flow to the U.S. altogether.

While that sounds dire, the reality is more complex. Each of the Canadian provinces the border is connected to the U.S. market. In fact, aside from Quebec, the border provinces all participate in either the Western Interconnection or the Eastern Interconnection, the large networks of high-voltage AC transmission lines that help move electricity from market to market. (Quebec is connected to the New England and New York system operators via AC-to-DC-to-AC ties.)

Depending on the time of year or long-term climate variables, the flow of electricity might go in either direction. That’s due in large part to the large penetration of hydroelectricity in the Canadian grid; when there’s a drought, as there was in British Columbia and Quebec in 2024, those hydro plants can’t produce enough power for local customers, while in wetter years, the excess power is sent south. The swings can be wide. In the summer of 2022, Canada on net exported more than 4,000 GWh per month to the U.S. In the summer of 2024, the U.S. exported around 1,000 GWh per month to Canada.

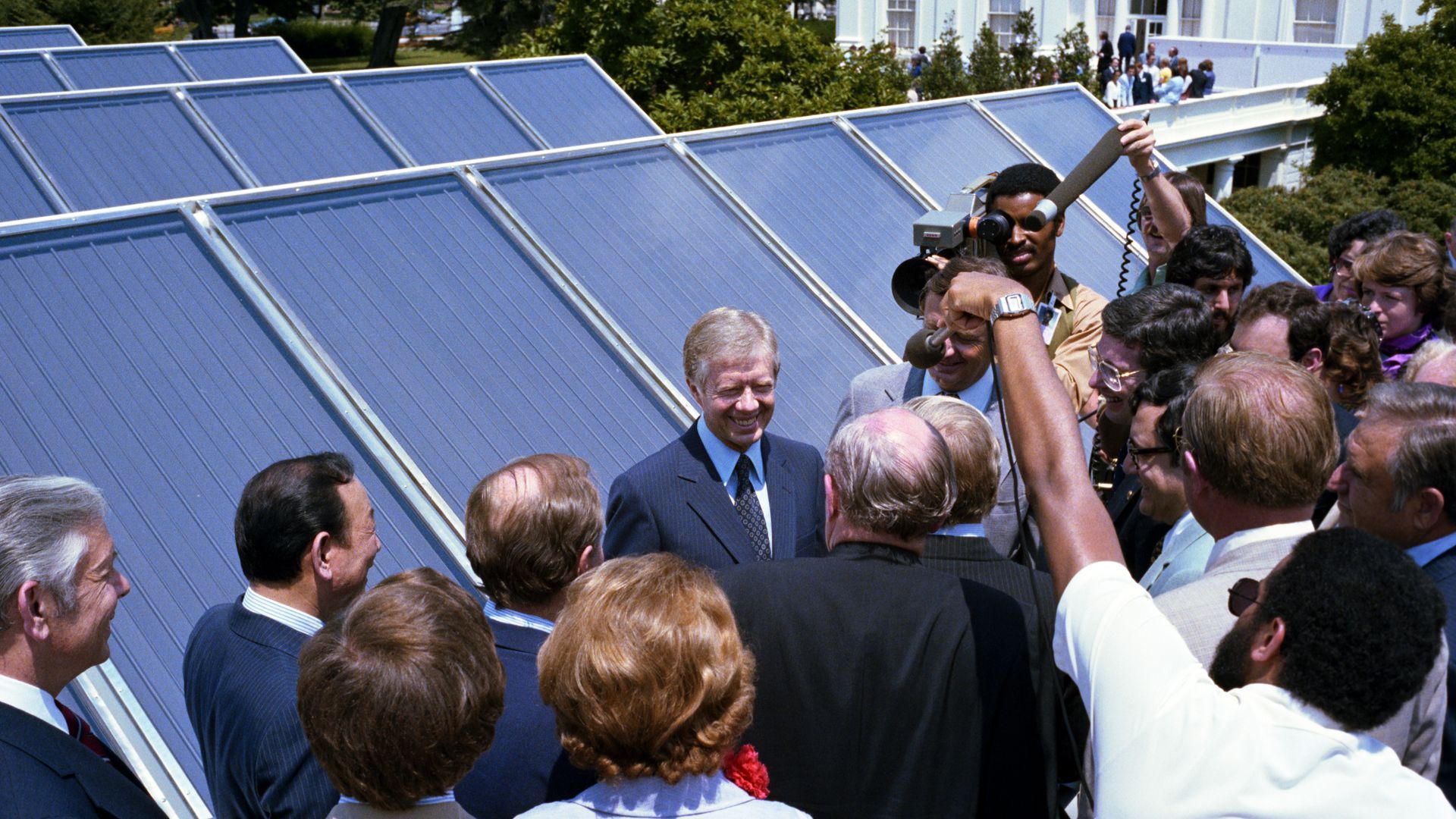

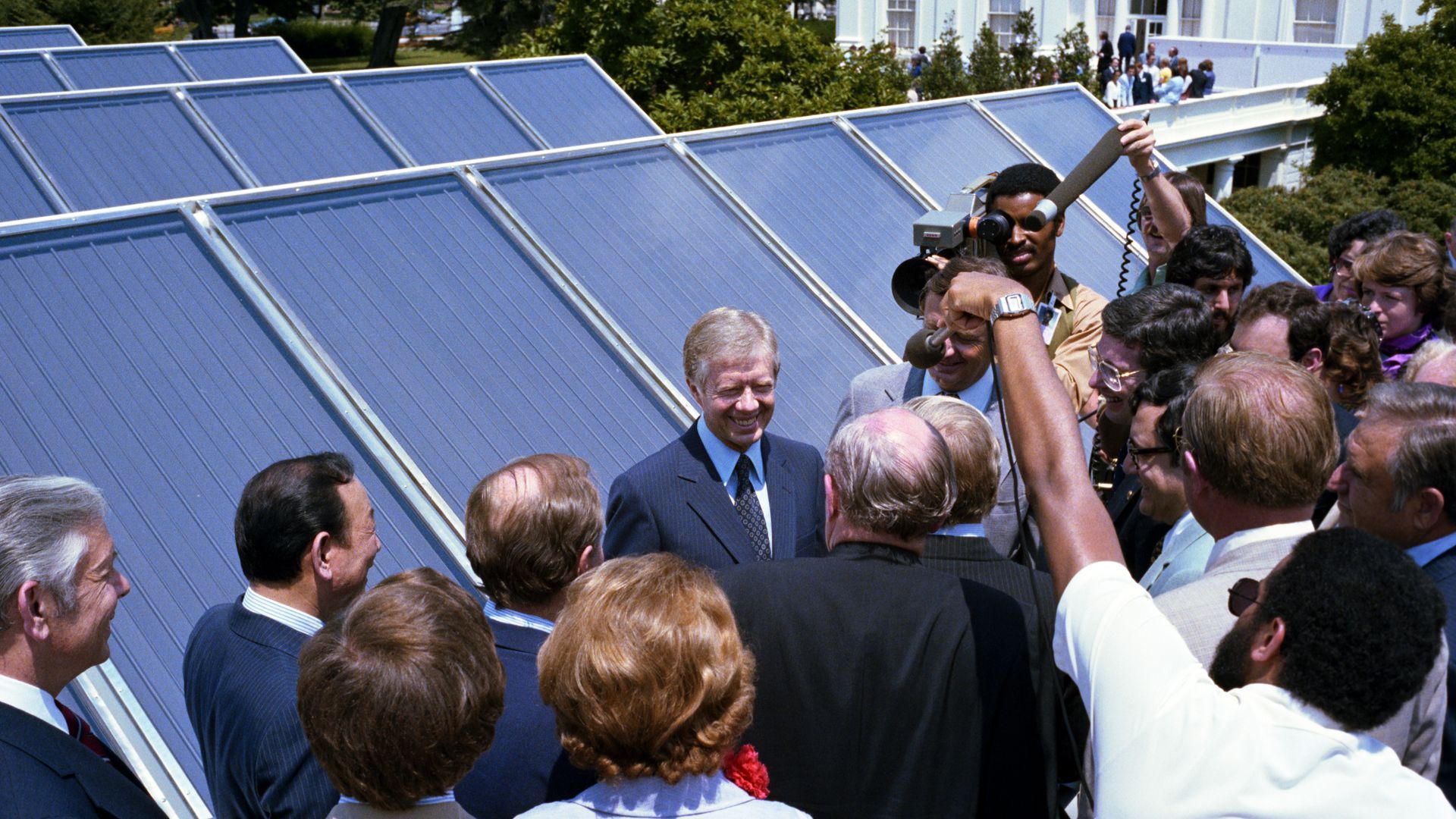

Jimmy Carter’s Solar Panels Remembered

An engineer who worked on the White House rooftop array recalls his brush with energy history.

That’s likely the bottom line for the trade war in its entirety. While the North American economies are so tightly bound that industrial supply chains often rely on multiple border crossings of components, the U.S., Canada, and Mexico are all large and diverse enough that losing access to a trade partner won’t cripple them. It will leave their consumers all a bit poorer, however.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.