Laser Process Purifies Silica

Laser Process Purifies Silica

Research team has developed a one-step method that uses a femtosecond laser to purify raw silica sand to over 99.99 percent purity.

A wide range of electronics components, from integrated circuits and smartphone sensors to photovoltaic cells, need purified silica sand as a key input. However, the standard process of purification involves leaching away impurities through chemical applications, which can involve multiple time-consuming or energy-intensive steps.

To make this an easier and faster process, a team of materials science and engineering researchers from the University of California-Davis and materials company Homerun Resources has developed a one-step laser-pulse process that purifies raw silica sand to over 99.99 percent purity. The method is the first phase in developing a carbon-neutral, environmentally friendly process that creates purified silicon from silica sand.

The goal of the team, consisting of Subhash Risbud, professor of materials science and engineering at UC-Davis, doctoral student Arish Naim, and Brian Leeners, CEO of Vancouver, B.C.-based materials company Homerun Resources, was to find the best treatment method for developing a green, economical, and industrially scalable process for silica purification.

The first step was homogenizing the raw silica sand so the application of heat will be uniform throughout the sample. The team then decided to attempt purification with several heating techniques, such as furnace treatments, but did not achieve the desired purity level.

The team then tried a femtosecond laser.

The sand was sealed in a vacuum and treated with lasers—pulsed every femtosecond for different time periods between two and 24 hours.

“This laser process did not require any pre- or post-chemical treatments,” Risbud said. “We aimed to minimize the electrical energy required in the overall process by carefully designing the mechanical treatments prior to the laser treatment.”

Drawn by the clean energy aspect of the project, Naim took the lead on conducting the experiments. After a few adjustments to the experimental parameters, she was surprised and excited to learn the X-ray fluorescence analysis revealed a purity level of over 99.99 percent.

“The extent of the purification of the quartz sand surprised us, as the elimination of impurities was only seen after a very specific time duration and not observed at other higher or lower laser treatment time durations,” Risbud said. “This is, however, compliant with the thermal diffusivity properties of SiO2.”

Another interesting aspect of the laser treatment was the phase transition from quartz to the cristobalite phase. The change in the topological properties and the reduction in size observed in the scanning electron microscope analysis revealed interesting features on the sand particles.

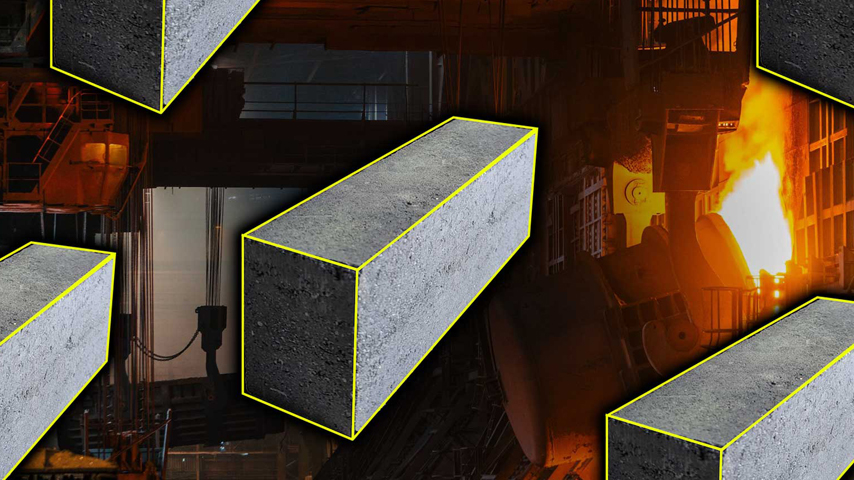

“The quartz particles showed coalescing during the laser treatment,” Risbud said. “The impact on mechanical behavior of sintered solids made from these high-purity quartz lumps will be of great interest to mechanical engineers.”

The research team hopes it can translate this lab-scale setup to an industrial-scale setup for commercial production. Further experiments are planned, including testing graphite and silica dioxide to produce carbides and composites with high strength and electronic properties for a variety of industries.

The research team hopes it can translate this lab-scale setup to an industrial-scale setup for commercial production. Further experiments are planned, including testing graphite and silica dioxide to produce carbides and composites with high strength and electronic properties for a variety of industries.

“Hopefully, we can create purified silicon carbide that is high enough grade to use in anodes for lithium-ion batteries,” Risbud said.

“Purifying the silica was the first step,” Naim said. “The end goal of this project is developing a value chain at the intersection of the battery and the mining industry to help the clean energy transition in the U.S. This will be an advantage to the silicon industry, to the battery industry and to silicon metallurgy. It’s a holistic project.”

Leeners believes the team can develop a fully green purification process for silica sand that will not require chemical treatments.

“Theoretically, you could have a solar energy generation facility creating the electricity that goes into the thermal processing done by lasers, which would then create silica that is recycled into creating more solar energy through silicon-based photovoltaics,” he said. “Our process has the potential to be an elegant industrial cycle.”

Mark Crawford is a technology writer in Corrales, N.M.

To make this an easier and faster process, a team of materials science and engineering researchers from the University of California-Davis and materials company Homerun Resources has developed a one-step laser-pulse process that purifies raw silica sand to over 99.99 percent purity. The method is the first phase in developing a carbon-neutral, environmentally friendly process that creates purified silicon from silica sand.

The goal of the team, consisting of Subhash Risbud, professor of materials science and engineering at UC-Davis, doctoral student Arish Naim, and Brian Leeners, CEO of Vancouver, B.C.-based materials company Homerun Resources, was to find the best treatment method for developing a green, economical, and industrially scalable process for silica purification.

The first step was homogenizing the raw silica sand so the application of heat will be uniform throughout the sample. The team then decided to attempt purification with several heating techniques, such as furnace treatments, but did not achieve the desired purity level.

The team then tried a femtosecond laser.

The sand was sealed in a vacuum and treated with lasers—pulsed every femtosecond for different time periods between two and 24 hours.

“This laser process did not require any pre- or post-chemical treatments,” Risbud said. “We aimed to minimize the electrical energy required in the overall process by carefully designing the mechanical treatments prior to the laser treatment.”

Drawn by the clean energy aspect of the project, Naim took the lead on conducting the experiments. After a few adjustments to the experimental parameters, she was surprised and excited to learn the X-ray fluorescence analysis revealed a purity level of over 99.99 percent.

“The extent of the purification of the quartz sand surprised us, as the elimination of impurities was only seen after a very specific time duration and not observed at other higher or lower laser treatment time durations,” Risbud said. “This is, however, compliant with the thermal diffusivity properties of SiO2.”

Another interesting aspect of the laser treatment was the phase transition from quartz to the cristobalite phase. The change in the topological properties and the reduction in size observed in the scanning electron microscope analysis revealed interesting features on the sand particles.

“The quartz particles showed coalescing during the laser treatment,” Risbud said. “The impact on mechanical behavior of sintered solids made from these high-purity quartz lumps will be of great interest to mechanical engineers.”

Aiming for industrial scale

Risbud is working to expand this project with additional funding from Homerun Resources to make graphite and carbide products. Purified silica can also be converted to silicon carbide, which is becoming increasingly sought-after in the semiconductor industry to replace silicon chips. The compound has the ability to operate under extreme conditions, which makes it practical for electric vehicles, medical sensors, space exploration, and renewable energy systems.

ME is Fully Digital

ASME members can access Mechanical Engineering magazine in its new, enhanced digital format. Everything you love about ME, now everywhere you go.

“Hopefully, we can create purified silicon carbide that is high enough grade to use in anodes for lithium-ion batteries,” Risbud said.

“Purifying the silica was the first step,” Naim said. “The end goal of this project is developing a value chain at the intersection of the battery and the mining industry to help the clean energy transition in the U.S. This will be an advantage to the silicon industry, to the battery industry and to silicon metallurgy. It’s a holistic project.”

Leeners believes the team can develop a fully green purification process for silica sand that will not require chemical treatments.

“Theoretically, you could have a solar energy generation facility creating the electricity that goes into the thermal processing done by lasers, which would then create silica that is recycled into creating more solar energy through silicon-based photovoltaics,” he said. “Our process has the potential to be an elegant industrial cycle.”

Mark Crawford is a technology writer in Corrales, N.M.