Tattooed on the Heart

Tattooed on the Heart

A new ultrathin and non-invasive electronic “tattoo” device can provide continuous heart monitoring in even the smallest patients.

After a pediatric patient has open heart surgery to fix a congenital heart defect, the standard of care calls for continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring for the next two weeks, even if the child has been discharged from the hospital. There’s only one problem, said Animesh Tandon, M.D., director of cardiovascular innovation at Cleveland Clinic’s Pediatric Cardiology Department. There are very few devices on the market that actually offer such monitoring and the ones that are available aren’t exactly kid-friendly.

“If you imagine the average three-year-old, you know they can’t sit still and that’s often true even after heart surgery,” he said. “So, you need to have a device that is comfortable. Something that the average three-year-old won’t peel off or throw away when you aren’t looking. It has to have a flexible shape. Many devices are designed for adults and have a fixed, flat shape. The curve of a child’s chest is physically smaller, with a greater curvature. These fixed shapes won’t conform to a child’s chest. That means that we have great difficulty monitoring what we need to.”

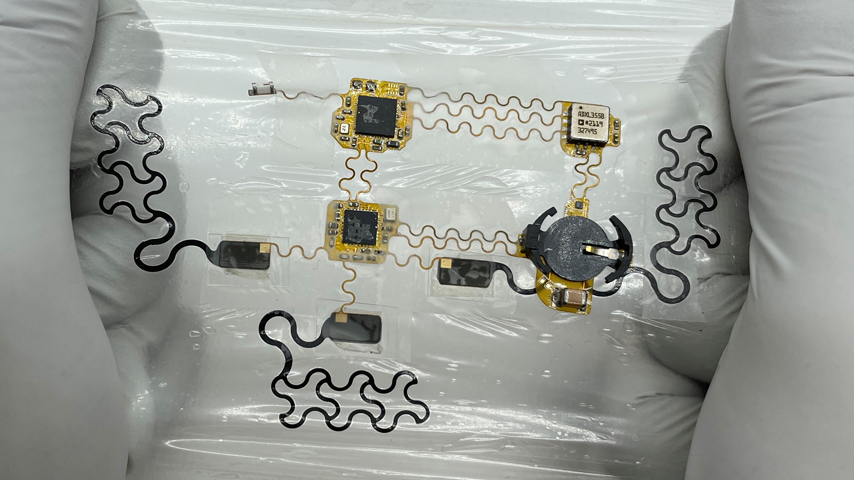

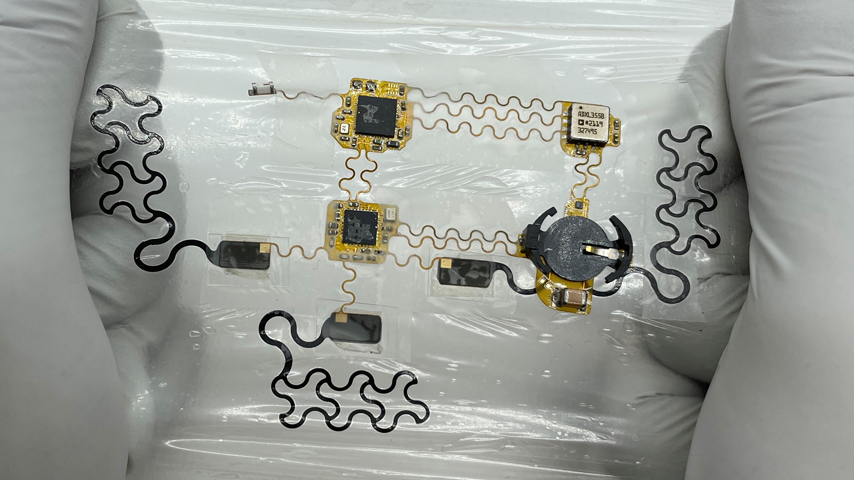

Now, a multi-disciplinary group led by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin have developed a new flexible tattoo-like monitoring device to allow continuous monitoring. The clear 2.5-gram device, called the chest e-tattoo, is an array of sensors and circuits connected by stretchable conductors, making it flexible enough to attach and record from chests of all sizes and shapes. Nanshu Lu, a professor at UT’s Department of Aerospace and Engineering Mechanics, said getting this kind of flexibility meant she and her colleagues had to be creative with the kind of hardware they used.

“If you go to the cardiologist for an ECG, they use a sort of gel patch to place a series of electrodes on your chest. Those patches are intrinsically thick and stiff and the gel itself can irritate the skin after long-term wear,” she said. “The first challenge we had to overcome in designing this device was to create a different kind of electrode to do the measurement. We ultimately came up with a dry graphite-based electrodes, which are very skin compatible, as well as thin and very conductive.”

The second challenge involved designing the electrodes to work on a device with a smaller footprint. The Holter monitor, the most common continuous ECG monitor, is a thick, rigid device slightly bigger than a deck of cards, that requires five electrodes to tentacle out from the base to get readings. Lu and colleagues broke down the rigid components necessary to get the electrical reading of the heart into four small “islands” to make it as small as possible. They also had to find ways to minimize power consumption, ultimately leveraging a penny-sized battery that offers 40+ hours of use.

“We designed our electronic circuits, including the all the read-out circuits, the Bluetooth chip, the battery, a vibration sensor, in such a way that we could organize them into these four islands,” she said. “We then interconnected them by using stretchable conductors for flexibility.”

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

The end result is a stretchable, two-layer circuit that conforms to the natural curvature of the chest without constraining movement.

“It’s a ‘wear it and forget it’ kind of system,” said Lu. “Because both layers are very thin and intrinsically stretchable, you’ll forget it is there within a few minutes of putting it on.”

Not only does the monitor record electrical activity, but it also boasts a vibration sensor that can record a seismocardiogram, the acoustic-mechanical signal that comes from the heart valves, which allows cardiologists to monitor cardiac time intervals. Abnormal cardiac time intervals can signal a variety of heart issues, ranging from cardiomyopathy to artery blockage.

“Knowing, over time, if there are changes in cardiac output could help us see there’s a problem before something catastrophic happens,” said Tandon. “We’ve never had the ability to do that because the technology didn’t exist before and you can only do an ultrasound on patients so often. Having this kind of measurement is going to be very useful for patients with congenital heart disease, regardless of age, so we can really understand what’s going on in a patient’s heart.”

More for You: A Miniature Skin Patch Can Tattoo

The team has already successfully tested the e-tattoo on five healthy adult patients and found it offered comparable measurements to other monitoring options. They will soon start testing it on some of Tandon’s pediatric patients after surgery to further validate it, while still working to shrink the size of the tattoo further. Tandon said it’s a “real breakthrough” in terms of form factor, especially for younger patients.

“This device allows us to get longer-term cardiac monitoring in a more comfortable way,” he said. “I’m excited about it because it’s something that can help us better help our patients.”

Kate Sukyl is a science and technology writer in Houston.

“If you imagine the average three-year-old, you know they can’t sit still and that’s often true even after heart surgery,” he said. “So, you need to have a device that is comfortable. Something that the average three-year-old won’t peel off or throw away when you aren’t looking. It has to have a flexible shape. Many devices are designed for adults and have a fixed, flat shape. The curve of a child’s chest is physically smaller, with a greater curvature. These fixed shapes won’t conform to a child’s chest. That means that we have great difficulty monitoring what we need to.”

Now, a multi-disciplinary group led by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin have developed a new flexible tattoo-like monitoring device to allow continuous monitoring. The clear 2.5-gram device, called the chest e-tattoo, is an array of sensors and circuits connected by stretchable conductors, making it flexible enough to attach and record from chests of all sizes and shapes. Nanshu Lu, a professor at UT’s Department of Aerospace and Engineering Mechanics, said getting this kind of flexibility meant she and her colleagues had to be creative with the kind of hardware they used.

“If you go to the cardiologist for an ECG, they use a sort of gel patch to place a series of electrodes on your chest. Those patches are intrinsically thick and stiff and the gel itself can irritate the skin after long-term wear,” she said. “The first challenge we had to overcome in designing this device was to create a different kind of electrode to do the measurement. We ultimately came up with a dry graphite-based electrodes, which are very skin compatible, as well as thin and very conductive.”

The second challenge involved designing the electrodes to work on a device with a smaller footprint. The Holter monitor, the most common continuous ECG monitor, is a thick, rigid device slightly bigger than a deck of cards, that requires five electrodes to tentacle out from the base to get readings. Lu and colleagues broke down the rigid components necessary to get the electrical reading of the heart into four small “islands” to make it as small as possible. They also had to find ways to minimize power consumption, ultimately leveraging a penny-sized battery that offers 40+ hours of use.

“We designed our electronic circuits, including the all the read-out circuits, the Bluetooth chip, the battery, a vibration sensor, in such a way that we could organize them into these four islands,” she said. “We then interconnected them by using stretchable conductors for flexibility.”

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

The end result is a stretchable, two-layer circuit that conforms to the natural curvature of the chest without constraining movement.

“It’s a ‘wear it and forget it’ kind of system,” said Lu. “Because both layers are very thin and intrinsically stretchable, you’ll forget it is there within a few minutes of putting it on.”

Not only does the monitor record electrical activity, but it also boasts a vibration sensor that can record a seismocardiogram, the acoustic-mechanical signal that comes from the heart valves, which allows cardiologists to monitor cardiac time intervals. Abnormal cardiac time intervals can signal a variety of heart issues, ranging from cardiomyopathy to artery blockage.

“Knowing, over time, if there are changes in cardiac output could help us see there’s a problem before something catastrophic happens,” said Tandon. “We’ve never had the ability to do that because the technology didn’t exist before and you can only do an ultrasound on patients so often. Having this kind of measurement is going to be very useful for patients with congenital heart disease, regardless of age, so we can really understand what’s going on in a patient’s heart.”

More for You: A Miniature Skin Patch Can Tattoo

The team has already successfully tested the e-tattoo on five healthy adult patients and found it offered comparable measurements to other monitoring options. They will soon start testing it on some of Tandon’s pediatric patients after surgery to further validate it, while still working to shrink the size of the tattoo further. Tandon said it’s a “real breakthrough” in terms of form factor, especially for younger patients.

“This device allows us to get longer-term cardiac monitoring in a more comfortable way,” he said. “I’m excited about it because it’s something that can help us better help our patients.”

Kate Sukyl is a science and technology writer in Houston.