In-Wheel Electric Motors Gain Traction Again

In-Wheel Electric Motors Gain Traction Again

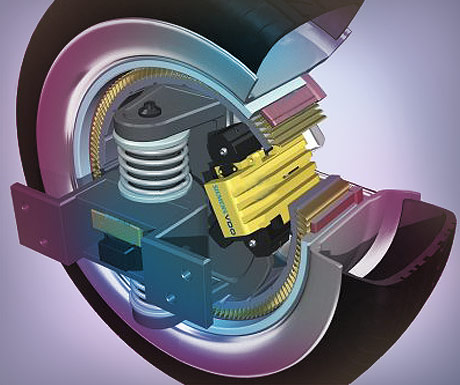

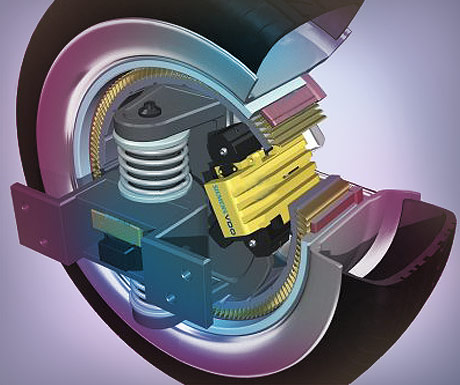

Seimen’s in-wheel electric system. Image courtesy of Seimens.

The growing popularity of hybrid and electric cars has revived interest in replacing a single internal combustion engine with in-wheel electric motors, a technology that many think of as a recent idea but one that has been around for more than a century.

Patents have been recorded as far back as the 1880s, and Ferdinand Porsche, known for many breakthroughs in the automotive field, even raced such a vehicle around the turn of the century–the 20th century.

"They did them then, and we do them now because it gets the motor outside the car and closer to the wheel," says Wayne Weaver, assistant professor, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI. "That makes a lot of sense in many cases."

Reduced Environmental Impact

Efficiency, resulting in reduced environmental impact, is a key reason the technology is getting a new look. Plus, eliminating the whole drive train–the driveshaft, differentials and drive axle–should mean fewer problems. Such a car would have motors on at least two wheels and possibly all four. This would decrease the power needed by any one motor and allow each motor to be smaller and lighter.

"If you have a motor right on the wheel, there is little space in between for things to go wrong," says Dr. Weaver, who conducts research in power electronics and energy systems.

However, the technology isn't without challenges, and auto and tire manufacturers as well as auto electronics suppliers have been working to overcome obstacles. "Someone will finally figure out a good way to get around the problems, or at least alleviate fears of [perceived] problems," Dr. Weaver says.

Among major multinationals whose names have been mentioned publicly as taking a look are General Motors, Honda, Michelin, Mitsubishi, and Siemens. Some, either independently or working in partnership with other companies, have gone as far as producing concept autos that have been shown at major shows in recent years.

"I'm sure all the car companies are looking at it," Dr. Weaver says.

The Unsprung Mass Challenge

A key obstacle is handling, or control, related to the unsprung mass. "When you put more mass [or weight] on the wheel itself, that takes away weight from the car so the suspensions get messed up," he explains.

If the wheel hits a bump or a pothole and the wheel is a lot heavier, there is no suspension to absorb the vibrations. Then, the wheels may bounce up off the surface, which not only affects ride comfort but the vehicle may lose traction. "Those handling problems may be tough to overcome," he adds.

Research is being done for making the motor lighter and putting some sort of suspension system inside the hub. Another issue is whether there should be concern about running high-voltage electrical lines through the wheel well, where they will be exposed to road debris, dust, and dirt being kicked up into the motor. "That's a much different environment than if the motor is inside a vehicle," Dr. Weaver says.

According to Dr. Weaver, "Everybody's trying to think of all the different technologies or angles to get competitively ahead on electric vehicles." The interest is high because the upside is big: greater fuel efficiency, better performance, and more design freedom.

Nancy S. Giges is an independent writer.

If you have a motor right on the wheel, there is little space in between for things to go wrong.Wayne Weaver, assistant professor, Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering at Michigan Technological University

.png?width=854&height=480&ext=.png)