5 Undersea Engineering Marvels

5 Undersea Engineering Marvels

The ocean is a hostile environment. These five technologies were able to survive beneath the waves to set enduring records.

Humanity has spent millennia working on and exploring the surface of the oceans. But the surface makes up only a tiny fraction of the ocean, and most of it is hostile to human habitation. The pressure is crushing, the temperatures are cold, and the gloom is all-encompassing. To explore those depths requires extraordinarily good engineering.

It’s a challenge, and one that engineers have risen to meet. Below are five examples of engineering marvels that have helped workers not only explore but also exploit the subsurface world for the benefit of humanity.

U.S. Navy officials hit upon an update of Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage in the 1500s. They sent the USS Triton, at the time the largest and most expensive nuclear submarine in the world, on an underwater circumnavigation of the Earth. In addition to being a technological triumph—the submarine would remain underwater for more than 60 straight days—it was a logistical feat, as the boat carried 120 days of provisions, including more than seven tons of frozen food, three tons of canned meat, and 1,285 pounds of potatoes.

The Triton averaged 18 knots over 60 days and 21 hours underwater. Not only does it still hold the record for fastest underwater circumnavigation, but it’s also faster than the record for motorized surface vessel.

Project Nekton was conceived as a counterpoint to Edmund Hillary’s climb of Mount Everest, the Earth’s highest point. In addition, the Navy hoped to learn about how sound waves traveled through the deepest layers of the ocean. After several dives of increasing depth, the Trieste reached the Challenger Deep, the deepest point in the ocean, on January 23, 1960.

The Trieste completed several other deep dives for the Navy before being decommissioned in 1966.

For offshore work, records are determined by depth of water. The depths reached by roughnecks at sea are impressive, and with as many as 40 wells per year being drilled at depths of greater than 5,000 feet (or nearly a mile), records are constantly being set. For instance, since 2021, four offshore wells have been drilled in waters 10,200 feet or deeper, a heretofore unheard of depth. That includes the current record holder, Ondjaba-1 off the coast of Angola, which went 11,900 feet.

Last year, the Colombian national oil company Ecopetrol began drilling what was expected to be the new record holder, a 12,900-foot well called Komodo-1 in the Caribbean Sea. However, a change in government policy put the project on hold, keeping Ondjaba-1’s record intact for now.

With solar power becoming increasingly cheap, some experts are looking to undersea power cables as a way to link large expanses of sunny desert to urban areas with large power demands. For instance, one ongoing project aims to link Australia and Singapore with a 2,700-mile undersea electric cable capable of carrying up to 20 GW. Several proposals have aimed to connect North Africa and Europe. And in 2023, investment bankers from France, Ireland, and Great Britain proposed a power line that would cross the Atlantic from Europe to Canada.

The current record for continuous stay underwater with depressurization is Joseph Dituri, who in 2023 spent 100 days at the bottom of a 30-foot-deep lagoon in Key Largo, Fla. Dituri lived in the former La Chalupa underwater habitat, which had been an undersea research platform off the coast of Puerto Rico. It was later towed to Florida and rechristened Jules’ Undersea Lodge.

Unlike submarines and bathyscaphes that deal with the crushing pressure of deep ocean water through use of a thick pressure vessel, Sealab and Jules’s Undersea Lodge prepared their residents to handle the depths through saturation diving techniques, including replacing the breathing air with a mixture of oxygen and helium. (Nitrogen in the blood can cause the painful and sometimes fatal bends.)

There are no plans at present for establishing permanent research stations on the ocean floor.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

It’s a challenge, and one that engineers have risen to meet. Below are five examples of engineering marvels that have helped workers not only explore but also exploit the subsurface world for the benefit of humanity.

Operation Sandblast

French novelist Jules Verne imagined both an advanced submarine as well as a trip around the world, but Operation Sandblast in 1960 combined both. It was a time of technological rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union, and after the surprise launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik in 1957, the Americans were eager for a showcase for their own advances.U.S. Navy officials hit upon an update of Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage in the 1500s. They sent the USS Triton, at the time the largest and most expensive nuclear submarine in the world, on an underwater circumnavigation of the Earth. In addition to being a technological triumph—the submarine would remain underwater for more than 60 straight days—it was a logistical feat, as the boat carried 120 days of provisions, including more than seven tons of frozen food, three tons of canned meat, and 1,285 pounds of potatoes.

The Triton averaged 18 knots over 60 days and 21 hours underwater. Not only does it still hold the record for fastest underwater circumnavigation, but it’s also faster than the record for motorized surface vessel.

Project Nekton

USS Triton wasn’t the only Navy ship setting records in that era. The Trieste was an Italian-designed, French-owned bathyscaphe, or free-diving submersible, that had been exploring the Mediterranean when the U.S. Navy purchased it in 1958. At first glance, the Trieste seemed large, extending 60 feet from bow to aft. But the crew of two was confined to an eight-foot-diameter sphere built from 3.5-inch steel to withstand the intense pressure of the bottom of the ocean. The rest of the ship was a series of gasoline-filled tanks for buoyancy and hoppers filled with iron pellets to make it sink.Project Nekton was conceived as a counterpoint to Edmund Hillary’s climb of Mount Everest, the Earth’s highest point. In addition, the Navy hoped to learn about how sound waves traveled through the deepest layers of the ocean. After several dives of increasing depth, the Trieste reached the Challenger Deep, the deepest point in the ocean, on January 23, 1960.

The Trieste completed several other deep dives for the Navy before being decommissioned in 1966.

Offshore drilling

Petroleum companies are going to great lengths to reach new oil deposits. The deepest onshore oil well on Sakhalin Island in Russia extends down more than 40,000 feet. Operating on an offshore platform, which requires lowering the drill string through the water before reaching the seafloor, is much more difficult.For offshore work, records are determined by depth of water. The depths reached by roughnecks at sea are impressive, and with as many as 40 wells per year being drilled at depths of greater than 5,000 feet (or nearly a mile), records are constantly being set. For instance, since 2021, four offshore wells have been drilled in waters 10,200 feet or deeper, a heretofore unheard of depth. That includes the current record holder, Ondjaba-1 off the coast of Angola, which went 11,900 feet.

Last year, the Colombian national oil company Ecopetrol began drilling what was expected to be the new record holder, a 12,900-foot well called Komodo-1 in the Caribbean Sea. However, a change in government policy put the project on hold, keeping Ondjaba-1’s record intact for now.

Undersea electric cables

Transoceanic communications cables have linked nations since the first sub-Atlantic telegraph line began operating in 1858. Underwater power cables are somewhat trickier to build, as the cables need to be sturdier and the losses due to resistance could rob the cable of much of its electricity. For now, the record-holder for longest undersea powerline is the 1.4 GW Viking Link interconnector, which extends 475 miles to link Denmark and England. Five other power lines link the United Kingdom to mainland Europe.With solar power becoming increasingly cheap, some experts are looking to undersea power cables as a way to link large expanses of sunny desert to urban areas with large power demands. For instance, one ongoing project aims to link Australia and Singapore with a 2,700-mile undersea electric cable capable of carrying up to 20 GW. Several proposals have aimed to connect North Africa and Europe. And in 2023, investment bankers from France, Ireland, and Great Britain proposed a power line that would cross the Atlantic from Europe to Canada.

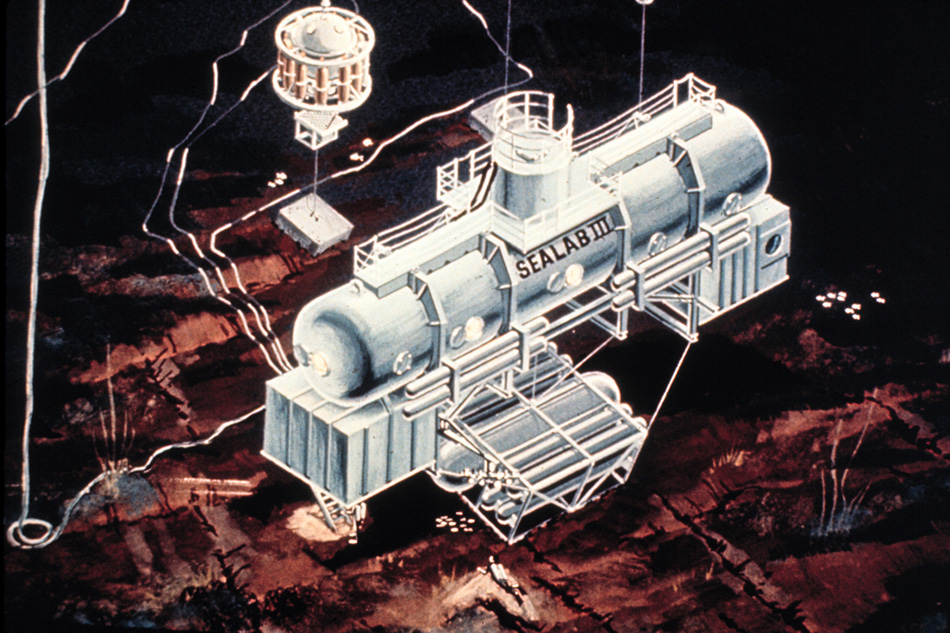

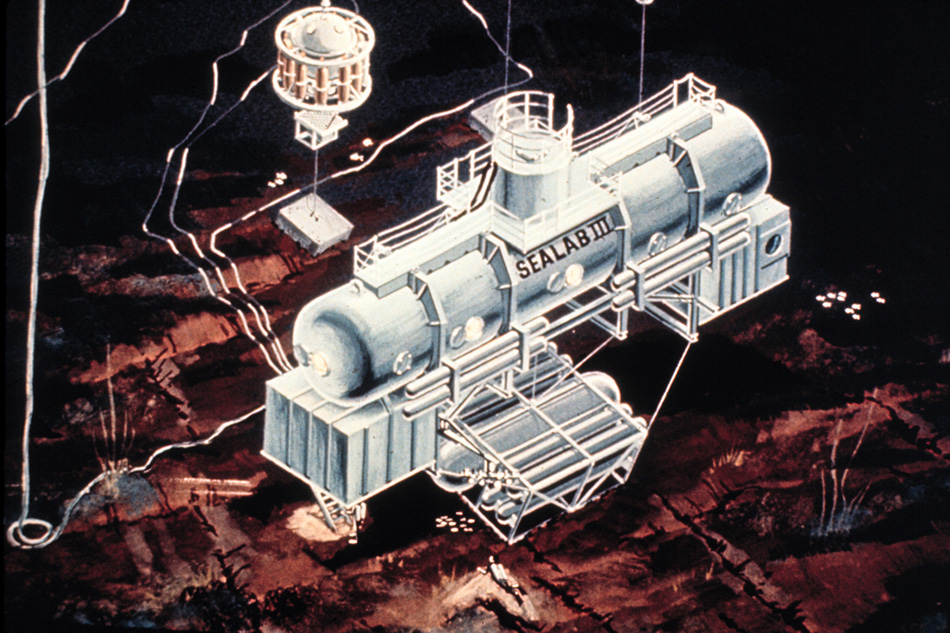

Undersea Habitats

As difficult as it is to visit the bottom of the ocean, few people have tried to live there. In the 1960s, the U.S. Navy tried to set up permanent underwater bases with its Sealab program, but the progression of increasingly larger bases was abandoned after one of the so-called aquanauts died.The current record for continuous stay underwater with depressurization is Joseph Dituri, who in 2023 spent 100 days at the bottom of a 30-foot-deep lagoon in Key Largo, Fla. Dituri lived in the former La Chalupa underwater habitat, which had been an undersea research platform off the coast of Puerto Rico. It was later towed to Florida and rechristened Jules’ Undersea Lodge.

Unlike submarines and bathyscaphes that deal with the crushing pressure of deep ocean water through use of a thick pressure vessel, Sealab and Jules’s Undersea Lodge prepared their residents to handle the depths through saturation diving techniques, including replacing the breathing air with a mixture of oxygen and helium. (Nitrogen in the blood can cause the painful and sometimes fatal bends.)

There are no plans at present for establishing permanent research stations on the ocean floor.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.