Alexander Lyman Holley

Alexander Lyman Holley

If Britain's Sir Henry Bessemer was the father of the steel industry, then Alexander Lyman Holley was the chief architect and engineer of its rise in the U.S. During his brief but remarkably productive career, Holley brought Bessemer's revolutionary steel manufacturing process to the states, improved upon it, and played a critical role in building a dozen of the nation's most important Bessemer steel works.

Holley was born in 1832 to a prominent Connecticut family with a long history in the iron business. His father, a former Connecticut governor, owned a cutlery factory where Holley gained his first exposure to industrial-scale manufacturing machinery. Although the family's wealth and connections (and his own robust intellect) positioned him for a distinguished career in law or politics, Holley was obsessed with machinery and the never-ending challenge of making things work better.

While studying science and engineering at Brown University in Providence, RI, Holley picked up practical experience in locomotive engineering and design at several local companies. While still in college he published and patented his first invention, a steam-engine cut-off valve.

His interest in railroad technology led to a close friendship with Zerah Colburn, a prominent rail engineer and author. Holley and Colburn traveled Europe by train, documenting the more advanced state of that continent's rail systems on behalf of top U.S. railroad executives. Their treatises on the subject helped inspire investment in infrastructure upgrades back home. Holley's own literary interests took shape at this point, as he began a prolific side career as a journalist, technical illustrator, and publisher of journals on railway technologies. He wrote numerous reference works, technical books, and articles for a wide range of specialty and general interest publications, including the New York Times, where he served for 30 years as a technical correspondent.

On his travels, Holley learned of Bessemer's new steel-making process, in which compressed air was blown over molten raw iron to remove impurities, creating high-quality steel far less expensively than traditional methods. Technical issues and a lack of scientific understanding of the underlying metallurgical processes impeded the technique's wide acceptance in Britain, but Holley's knife-factory background and Ivy League training enabled him to perceive the exciting potential of the Bessemer process.

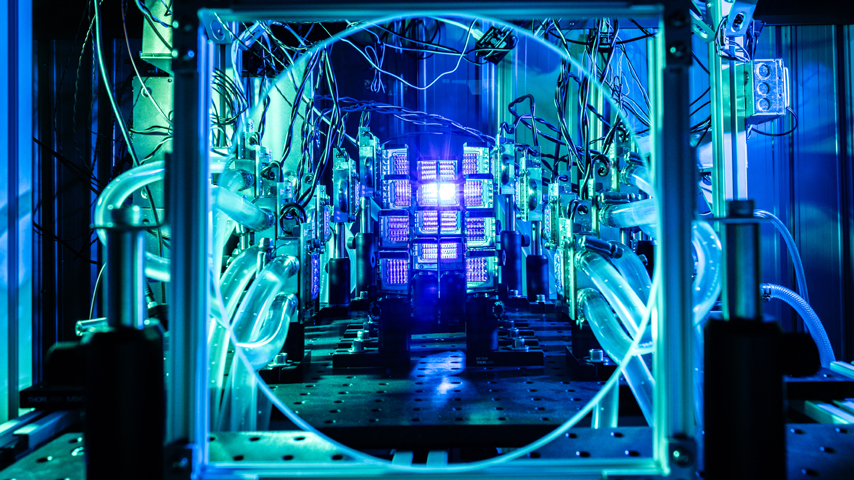

In 1863, Holley purchased the rights to bring the Bessemer process to the U.S. Ten of his 15 lifetime patents were for improvements in the process that adapted it for conditions in the U.S. Soon, enormous Bessemer steel works took shape in cities like Troy, NY, and Harrisburg, PA. These and a dozen other steel towns across the industrial east fed the nation's growing hunger for cheap, high-quality Bessemer steel. Holley's mills churned out steel for the bridges, railways, skyscrapers, and battleships that would make the U.S. the strongest economic power in the world.

As with his journalism, Holley's professional endeavors were geared toward bringing people of different backgrounds together around key topics in science and engineering. His passion for research-driven progress in the practice of engineering led him to play a seminal role in the founding of the nation's most important professional organizations aimed at education, standardization, and disciplinary excellence.

He was considered a leading spirit in the founding of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), and he chaired the first meeting of its founding members in 1880. His efforts helped to frame the intellectual parameters of the mechanical engineering profession and of the ASME organization itself. He played similar roles in the creation of the Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers (AIME), and the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

The break-neck pace of Holley's work eventually took its toll on his health. He died from peritonitis in 1882 at age 49. Less than a decade after his death, the three organizations with which he was most closely linked – ASME, ASCE, and AIME – joined forces to commission the 12 ½ foot tall bronze and limestone Holley memorial, which still serves as a popular meeting spot in Manhattan's Washington Square Park. Today, just as he did in life, Holley continues to bring people together.

Michael MacRae is an independent writer.

Holley's mills churned out steel for the bridges, railways, skyscrapers, and battleships that would make the U.S. the strongest economic power in the world.