Better Sensors Allow Engineers to Study Foot Clearance

Better Sensors Allow Engineers to Study Foot Clearance

When feet drag the ground, the risk of tripping rises. Now there’s a way to measure a patient’s foot clearance while walking, to reduce that risk.

How high off the ground are our feet when we swing them forward while walking? It’s an essential question, not just to add to our academic understanding of human mobility, but to keep anyone with an impaired gait from tripping.

The answer is that the minimum foot clearance—the space between the ground and the lowest point of the foot’s sweep as it steps forward—is different for everyone. And for anyone that needs a prosthetic leg or some other form of ambulatory intervention, measuring that distance with precision is crucial.

“In the context of movement and gait and health, we always want to know how regular, and how high quality, a person’s movement is,” said Peter Adamczyk, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin, where he directs the Biomechatronics, Assistive Devices, Gait Engineering and Rehabilitation Laboratory. “Falling is dangerous, and we want to use any way we can to prevent it.”

Adamczyk and his colleagues have set out to find a way to measure minimum foot clearance on any individual.

“We’re trying to evaluate what difference X or Y thing makes to a person’s likelihood of catching their toes, for example, or scuffing against the ground,” he said. “There has been no way to really measure that anywhere except in a laboratory.” And the laboratory is not the best place to examine a person strolling at their most natural.

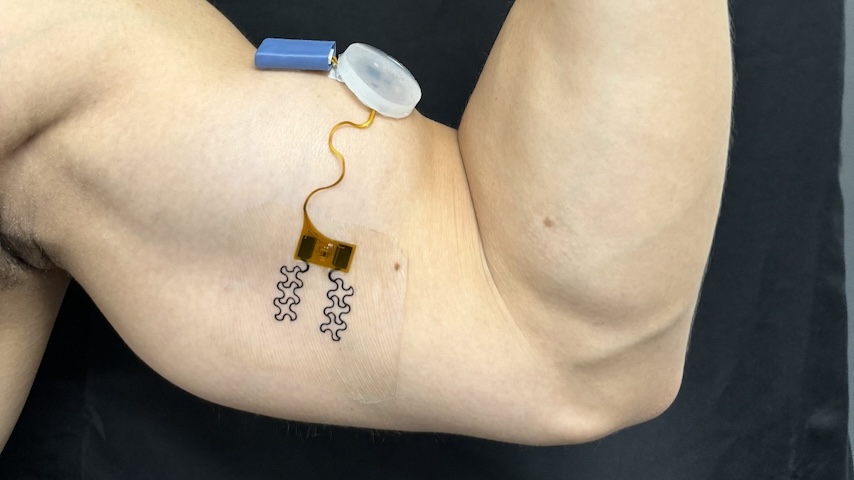

To measure foot clearance in a more real-world setting, Adamczyk attached inertial measurement units, or IMUs, to the shoe’s laces. Measuring acceleration and velocity in three axes, the IMU’s data was used to reconstruct where a foot moved in relation to where it started, including how high it was at the lowest point in its swing.

“The shortcoming, at that point, was that we had reconstructed only a single point—the sensor—which could tell us about changes in foot height overall, but not about ground clearance,” he said.

Needless to say, the location of the sensor, on the shoe and in space, is not the location where the shoe hits that ground. Any measure of ground clearance has to be able to locate the riskiest point on a foot mid-stride.

Needless to say, the location of the sensor, on the shoe and in space, is not the location where the shoe hits that ground. Any measure of ground clearance has to be able to locate the riskiest point on a foot mid-stride.

“That got us thinking about how we could take this accurate vertical information and actually cobble on a foot shaped model that lets us do real ground clearance,” Adamczyk said.

By adding a calibration device to the pouch that held the IMU, they were able to know where the flat surfaces of a scanned shoe would be in relation to the IMU. The scan/IMU combo allowed them to see the foot’s orientation with every stride, including roll, pitch, and yaw.

More on This Topic: Advanced Prosthetics Transform Veterans' Lives

“Now, when you lift up your toes, we know not only that the IMU was lifted up by that action, but that the heel actually went down a little bit and got closer to the ground,” Adamczyk said.

Prior to making the foot scan, the actual location of the ground had not been part of the equation—all changes in foot height were relative. With the foot scan as part of the model, the researchers were able to locate the ground and include it in the model.

Right now, Adamczyk and his team are looking to find better ways to calculate stairs, ramps, and turns. They’re also using the technology with prosthetics, so that an artificial foot can use the data in real time to position itself one way during the swing phase but reorient to prepare for the following stance phase.

But already the system can help people who use orthotics, or who struggle with Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis. Adamczyk’s team is running experiments where users wear the sensor for a week or more to help determine the best method to keep their minimum foot clearance at safe heights.

“The long-standing goals of this whole branch of the field are to use it as part of an assessment tool,” Adamczyk said. “Or in our case, use it to help people choose the right intervention.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer in Westfield, N.J.

The answer is that the minimum foot clearance—the space between the ground and the lowest point of the foot’s sweep as it steps forward—is different for everyone. And for anyone that needs a prosthetic leg or some other form of ambulatory intervention, measuring that distance with precision is crucial.

“In the context of movement and gait and health, we always want to know how regular, and how high quality, a person’s movement is,” said Peter Adamczyk, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin, where he directs the Biomechatronics, Assistive Devices, Gait Engineering and Rehabilitation Laboratory. “Falling is dangerous, and we want to use any way we can to prevent it.”

Adamczyk and his colleagues have set out to find a way to measure minimum foot clearance on any individual.

“We’re trying to evaluate what difference X or Y thing makes to a person’s likelihood of catching their toes, for example, or scuffing against the ground,” he said. “There has been no way to really measure that anywhere except in a laboratory.” And the laboratory is not the best place to examine a person strolling at their most natural.

To measure foot clearance in a more real-world setting, Adamczyk attached inertial measurement units, or IMUs, to the shoe’s laces. Measuring acceleration and velocity in three axes, the IMU’s data was used to reconstruct where a foot moved in relation to where it started, including how high it was at the lowest point in its swing.

“The shortcoming, at that point, was that we had reconstructed only a single point—the sensor—which could tell us about changes in foot height overall, but not about ground clearance,” he said.

High-Impact Engineering

Mechanical Engineering magazine is available for ASME members. Read the magazine wherever you go!

“That got us thinking about how we could take this accurate vertical information and actually cobble on a foot shaped model that lets us do real ground clearance,” Adamczyk said.

By adding a calibration device to the pouch that held the IMU, they were able to know where the flat surfaces of a scanned shoe would be in relation to the IMU. The scan/IMU combo allowed them to see the foot’s orientation with every stride, including roll, pitch, and yaw.

More on This Topic: Advanced Prosthetics Transform Veterans' Lives

“Now, when you lift up your toes, we know not only that the IMU was lifted up by that action, but that the heel actually went down a little bit and got closer to the ground,” Adamczyk said.

Prior to making the foot scan, the actual location of the ground had not been part of the equation—all changes in foot height were relative. With the foot scan as part of the model, the researchers were able to locate the ground and include it in the model.

Right now, Adamczyk and his team are looking to find better ways to calculate stairs, ramps, and turns. They’re also using the technology with prosthetics, so that an artificial foot can use the data in real time to position itself one way during the swing phase but reorient to prepare for the following stance phase.

But already the system can help people who use orthotics, or who struggle with Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis. Adamczyk’s team is running experiments where users wear the sensor for a week or more to help determine the best method to keep their minimum foot clearance at safe heights.

“The long-standing goals of this whole branch of the field are to use it as part of an assessment tool,” Adamczyk said. “Or in our case, use it to help people choose the right intervention.”

Michael Abrams is a technology writer in Westfield, N.J.