Magnetic Bearings Support Space Station Scrubber

Magnetic Bearings Support Space Station Scrubber

The system that removes carbon dioxide from the air aboard the International Space Station received an efficiency upgrade.

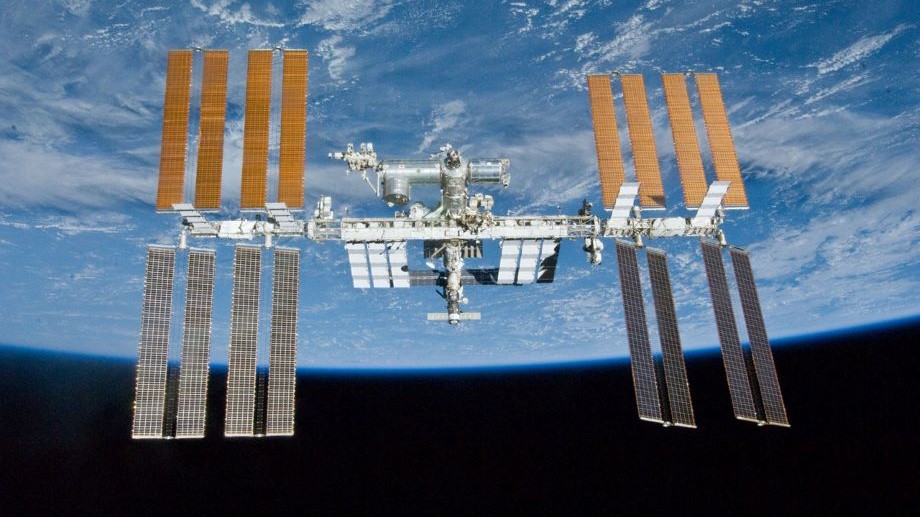

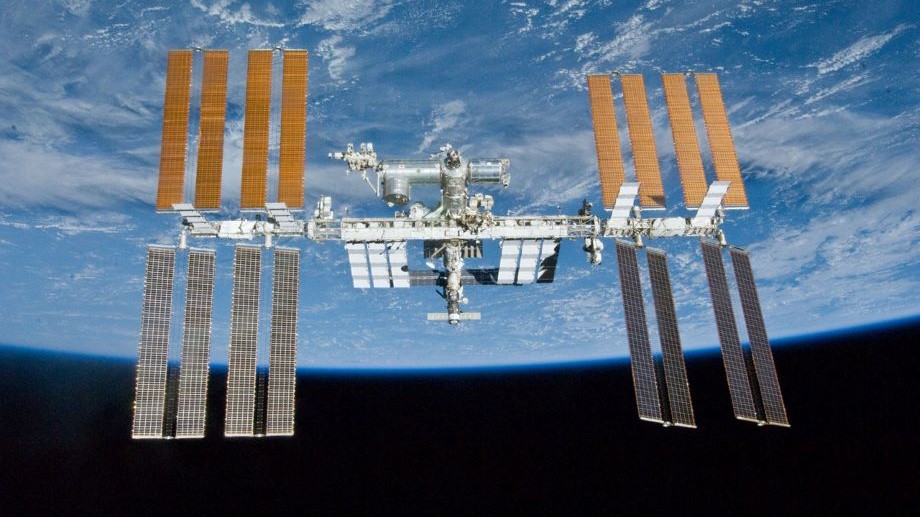

The International Space Station is a self-contained orbiting habitat, which means that maintaining a healthy environment is crucially important. One critical system is the unit that removes carbon dioxide from the air. If too much CO2 builds up, it could be harmful or even deadly to crew members.

Recently, a new scrubber was installed aboard the ISS and it features some advanced air flow technology. The blower, which can move up to 40 cubic feet per minute over beds of carbon dioxide-absorbing material, uses magnetic bearings rather than the air bearings used in the station’s original scrubbing system. That should improve the reliability of the systems, said Matthew Farides, an engineer who is the director of business development at Calnetix Technologies, the company that built the new blower for NASA.

“Air bearings can be prone to wear with many starts and stops, or with improperly filtered air,” Farides said. “While there is a weight and size penalty compared to air bearings, magnetic bearings do not have any components that wear out as long as they are powered. Magnetic bearings will also tolerate pressure fluctuations more readily, and will work reliably at lower pressures, enabling the possibility for near-vacuum operation if configured for such.”

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., built the Four-Bed Carbon Dioxide Scrubber, which uses commercial adsorbent materials to filter carbon dioxide from the ISS’s air. Compared to the previous system, the new scrubber promises reduced power consumption, improved thermal stability, and a longer lifespan for the adsorbent materials. The design also has replaceable air filters, which is important in an environment where food particles and even flaking skin can stay suspended in the air indefinitely.

The scrubber is being demonstrated now, but after a one-year trial it will be permanently integrated into the station’s life support system.

According to Farides, Calnetix has been making magnetic bearings for 25 years, but NASA’s design brief for the blower was challenging. “Calnetix was required to combine and integrate many technologies into a turn-key solution,” Farides said, “including magnetic bearings, surface-mount permanent-magnet motor, compressor wheel and volute, motor and blower housings (and related cooling design).” The magnetic bearing controller and variable speed motor drive electronics also needed to be integrated within a common electronics controller.

“Resizing, packaging, and integration work required a significant engineering effort spanning several years,” Farides said.

Also, unlike the terrestrial applications the company has worked with up to now, designing for space means having to solve issues involving the vibration and shock of launch and electromagnetic interference and electrical power-quality fluctuations.

Weightlessness—also a major difference from Earth—was less of a problem, Farides said. While Earth-based magnetic bearings factor in the constant pull of gravity, that compensation wasn’t needed for orbit, so in a sense the space mission was easier.

Farides noted that the blower needs to operate at very high speeds—up to 60,000 rpm—which made reliability all the more crucial. “This is quite ‘fast’ for a rotational speed.” Farides said. “60,000 rpm is about 10-times faster than the redline of a standard gasoline engine in a high-performance vehicle.”

While reliability is important for low Earth orbit, it is imperative on longer-duration missions. NASA has a goal of launching Artemis II, a crewed mission to the moon, by late 2024, and an expedition to Mars is part of the agency’s longer-term plans. If the CO2 scrubber fails during one of those missions, the crew would have to abandon the mission and head back to Earth as quickly as possible, as was the case with Apollo 13.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

Recently, a new scrubber was installed aboard the ISS and it features some advanced air flow technology. The blower, which can move up to 40 cubic feet per minute over beds of carbon dioxide-absorbing material, uses magnetic bearings rather than the air bearings used in the station’s original scrubbing system. That should improve the reliability of the systems, said Matthew Farides, an engineer who is the director of business development at Calnetix Technologies, the company that built the new blower for NASA.

“Air bearings can be prone to wear with many starts and stops, or with improperly filtered air,” Farides said. “While there is a weight and size penalty compared to air bearings, magnetic bearings do not have any components that wear out as long as they are powered. Magnetic bearings will also tolerate pressure fluctuations more readily, and will work reliably at lower pressures, enabling the possibility for near-vacuum operation if configured for such.”

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., built the Four-Bed Carbon Dioxide Scrubber, which uses commercial adsorbent materials to filter carbon dioxide from the ISS’s air. Compared to the previous system, the new scrubber promises reduced power consumption, improved thermal stability, and a longer lifespan for the adsorbent materials. The design also has replaceable air filters, which is important in an environment where food particles and even flaking skin can stay suspended in the air indefinitely.

The scrubber is being demonstrated now, but after a one-year trial it will be permanently integrated into the station’s life support system.

According to Farides, Calnetix has been making magnetic bearings for 25 years, but NASA’s design brief for the blower was challenging. “Calnetix was required to combine and integrate many technologies into a turn-key solution,” Farides said, “including magnetic bearings, surface-mount permanent-magnet motor, compressor wheel and volute, motor and blower housings (and related cooling design).” The magnetic bearing controller and variable speed motor drive electronics also needed to be integrated within a common electronics controller.

“Resizing, packaging, and integration work required a significant engineering effort spanning several years,” Farides said.

Also, unlike the terrestrial applications the company has worked with up to now, designing for space means having to solve issues involving the vibration and shock of launch and electromagnetic interference and electrical power-quality fluctuations.

Weightlessness—also a major difference from Earth—was less of a problem, Farides said. While Earth-based magnetic bearings factor in the constant pull of gravity, that compensation wasn’t needed for orbit, so in a sense the space mission was easier.

Farides noted that the blower needs to operate at very high speeds—up to 60,000 rpm—which made reliability all the more crucial. “This is quite ‘fast’ for a rotational speed.” Farides said. “60,000 rpm is about 10-times faster than the redline of a standard gasoline engine in a high-performance vehicle.”

While reliability is important for low Earth orbit, it is imperative on longer-duration missions. NASA has a goal of launching Artemis II, a crewed mission to the moon, by late 2024, and an expedition to Mars is part of the agency’s longer-term plans. If the CO2 scrubber fails during one of those missions, the crew would have to abandon the mission and head back to Earth as quickly as possible, as was the case with Apollo 13.

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.