Simple, Sophisticated Sensing Systems Collect Critical Information

Simple, Sophisticated Sensing Systems Collect Critical Information

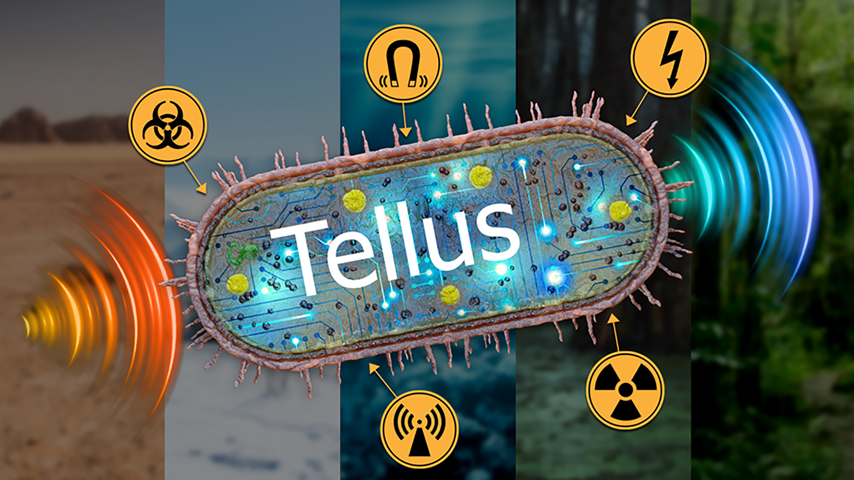

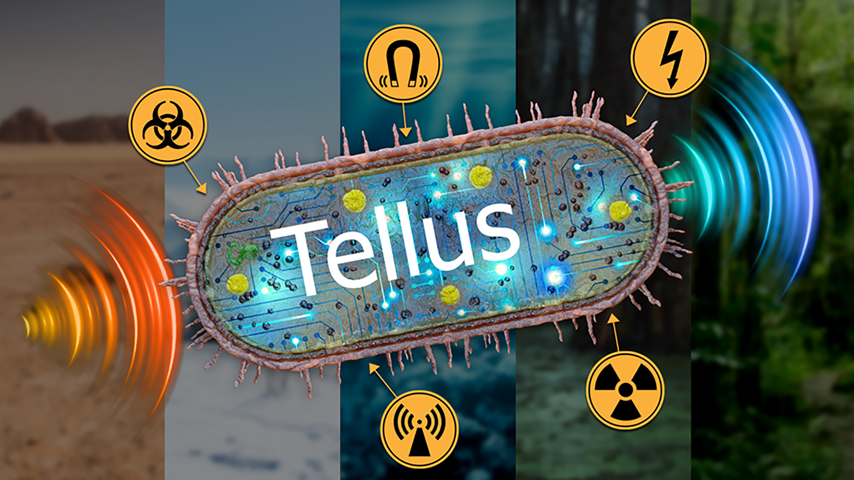

With the roll-out of the new Tellus program, DARPA is looking to test the boundaries of microbe-based sensing technologies.

They surround us—living in the water, soil, air, and even within our own bodies.

Microbes, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa, algae, and viruses, are too small to be seen with the naked eye. But despite their small statures, they contain sophisticated sensory systems, releasing specific proteins in response to the different stimuli they encounter. As microbes are remarkably resilient—and don’t require batteries—they have the potential to be developed as biological sensors that can collect vital information about the environments they inhabit, complementing monitoring data taken in by electrical or man-made systems.

“It’s incredibly fascinating to see what microbes can do naturally in the environment,” said Linda Chrisey, program manager of the Biological Technologies Office at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). “They’re found everywhere on the planet. They can survive in pretty much any environment they’re in. And they’ve really evolved so they can sense what’s happening around them in the environment and then respond in a way that typically benefits them.

“It makes them an interesting target—and offers the potential for us to take one of these microorganisms and ask them to detect chemical X or produce signal Y so we can explore useful things they might do for us.”

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

Over the past decade, scientists have proved that microbes, with a little synthetic biology and engineering, are capable of much, much more. Research studies have shown that, under the right conditions, they can produce an electric current that has enough force to actuate a tiny gear. They can change colors when they encounter specific toxins. They can even sense and respond to physical stimuli such as light or magnetic fields.

“People have been able to prove a lot of interesting applications for these kinds of sensors in the laboratory under ideal conditions,” Chrisey said. “But what happens when conditions aren’t ideal? What happens if you are trying to sense something, maybe a specific chemical or smoke in the air, but there are other things also happening in that environment? How well can these microbes do?”

To that end, DARPA recently announced the Tellus program, a new 2.5-year initiative to “advance remote environmental sense-and-respond platforms” using microbes. The aim of the program is to better define the range of different microbes’ sensing capabilities, through a combination of changing environmental conditions.

“The genesis of Tellus is really about understanding, in detail, what microbes can do. This program will be done in the lab—but we are asking the scientists who submit proposals with unique combinations of environmental parameters to see how well the microbes work in different situations,” Chrisey said.

More for You: Glowing Worms Detect Foul Air

“For example, in the terrestrial environment, there may be dusty, smokey, or hyperbaric conditions. We want laboratories to show us they have the capability to set up that terrestrial environment, but maybe have smoke present, and then assess the ability of the microbe sensors to detect the stimuli they’ve designed the organism for and produce the output signal that they’ve programmed their organism to generate in that scenario.”

Chrisey said the goal of the Tellus program is to cover as many environmental condition combinations as possible—and understand how they might affect sensing and response performance. She and her team are also interested in capabilities to do stand-off or remote detection. Understanding the full capabilities of different microbes, she said, is necessary to develop agile, reliable, and durable monitoring systems for a variety of different future applications.

“We expect there will probably be some environments or some stimuli or some signals to be transduced that are going to be very difficult for microbes to do. But we don’t know which ones yet,” she said. “That’s part of the learning process and, as we work through these different combinations, we can inform future efforts. There may be certain environments or certain problems that we shouldn’t be asking microbes to solve.”

Chrisey and colleagues are currently reviewing proposals—and she said she is excited to see what different laboratories can offer. She said, based on what they learn over the next few years, she expects to see even more innovative applications to emerge.

“Microbes have superpowers—they can do a lot of really cool things,” she said. “The Tellus program will pressure test those capabilities, using different combinations of environmental parameters. We’re going to learn a lot as we go, not only about what microbes can do, but also about the robustness of synthetic biology and the tools we’ve been developing that have allowed us to get to the point where we can embark on this kind of program.

“How reliable are microbes as sensors? How robust can they be when they start stepping out of the comfort zone of a controlled laboratory setting and start layering on new levels of complexity? Those are the kinds of questions we need to answer before we can take these kind of systems any further.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston, Tex.

Microbes, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa, algae, and viruses, are too small to be seen with the naked eye. But despite their small statures, they contain sophisticated sensory systems, releasing specific proteins in response to the different stimuli they encounter. As microbes are remarkably resilient—and don’t require batteries—they have the potential to be developed as biological sensors that can collect vital information about the environments they inhabit, complementing monitoring data taken in by electrical or man-made systems.

Managing microbes

“It’s incredibly fascinating to see what microbes can do naturally in the environment,” said Linda Chrisey, program manager of the Biological Technologies Office at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). “They’re found everywhere on the planet. They can survive in pretty much any environment they’re in. And they’ve really evolved so they can sense what’s happening around them in the environment and then respond in a way that typically benefits them.

“It makes them an interesting target—and offers the potential for us to take one of these microorganisms and ask them to detect chemical X or produce signal Y so we can explore useful things they might do for us.”

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

Over the past decade, scientists have proved that microbes, with a little synthetic biology and engineering, are capable of much, much more. Research studies have shown that, under the right conditions, they can produce an electric current that has enough force to actuate a tiny gear. They can change colors when they encounter specific toxins. They can even sense and respond to physical stimuli such as light or magnetic fields.

“People have been able to prove a lot of interesting applications for these kinds of sensors in the laboratory under ideal conditions,” Chrisey said. “But what happens when conditions aren’t ideal? What happens if you are trying to sense something, maybe a specific chemical or smoke in the air, but there are other things also happening in that environment? How well can these microbes do?”

Tellus is here

To that end, DARPA recently announced the Tellus program, a new 2.5-year initiative to “advance remote environmental sense-and-respond platforms” using microbes. The aim of the program is to better define the range of different microbes’ sensing capabilities, through a combination of changing environmental conditions.

“The genesis of Tellus is really about understanding, in detail, what microbes can do. This program will be done in the lab—but we are asking the scientists who submit proposals with unique combinations of environmental parameters to see how well the microbes work in different situations,” Chrisey said.

More for You: Glowing Worms Detect Foul Air

“For example, in the terrestrial environment, there may be dusty, smokey, or hyperbaric conditions. We want laboratories to show us they have the capability to set up that terrestrial environment, but maybe have smoke present, and then assess the ability of the microbe sensors to detect the stimuli they’ve designed the organism for and produce the output signal that they’ve programmed their organism to generate in that scenario.”

Chrisey said the goal of the Tellus program is to cover as many environmental condition combinations as possible—and understand how they might affect sensing and response performance. She and her team are also interested in capabilities to do stand-off or remote detection. Understanding the full capabilities of different microbes, she said, is necessary to develop agile, reliable, and durable monitoring systems for a variety of different future applications.

Expect the unexpected

“We expect there will probably be some environments or some stimuli or some signals to be transduced that are going to be very difficult for microbes to do. But we don’t know which ones yet,” she said. “That’s part of the learning process and, as we work through these different combinations, we can inform future efforts. There may be certain environments or certain problems that we shouldn’t be asking microbes to solve.”

Chrisey and colleagues are currently reviewing proposals—and she said she is excited to see what different laboratories can offer. She said, based on what they learn over the next few years, she expects to see even more innovative applications to emerge.

“Microbes have superpowers—they can do a lot of really cool things,” she said. “The Tellus program will pressure test those capabilities, using different combinations of environmental parameters. We’re going to learn a lot as we go, not only about what microbes can do, but also about the robustness of synthetic biology and the tools we’ve been developing that have allowed us to get to the point where we can embark on this kind of program.

“How reliable are microbes as sensors? How robust can they be when they start stepping out of the comfort zone of a controlled laboratory setting and start layering on new levels of complexity? Those are the kinds of questions we need to answer before we can take these kind of systems any further.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston, Tex.