Sparking More STEM Sparks

Sparking More STEM Sparks

Corporations are increasing their STEM education efforts to create a skilled workforce, launch careers, and make kids fall in love with science.

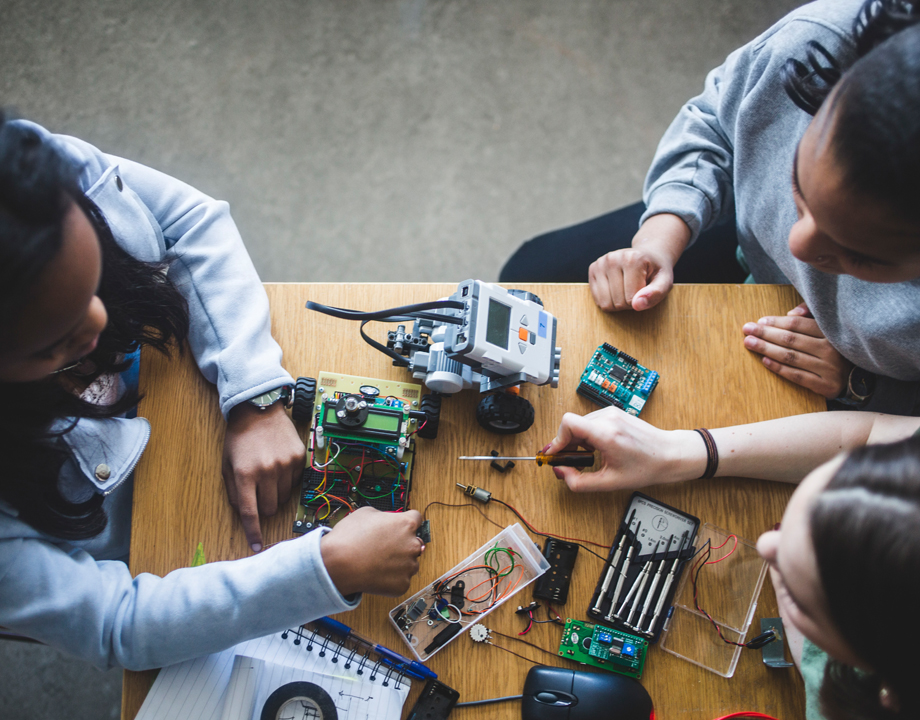

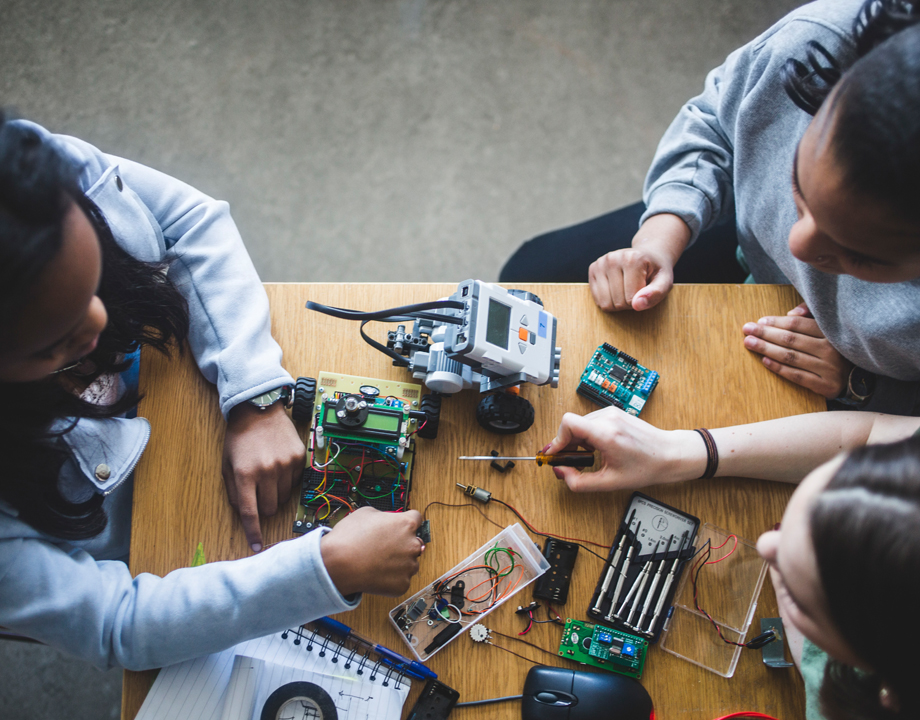

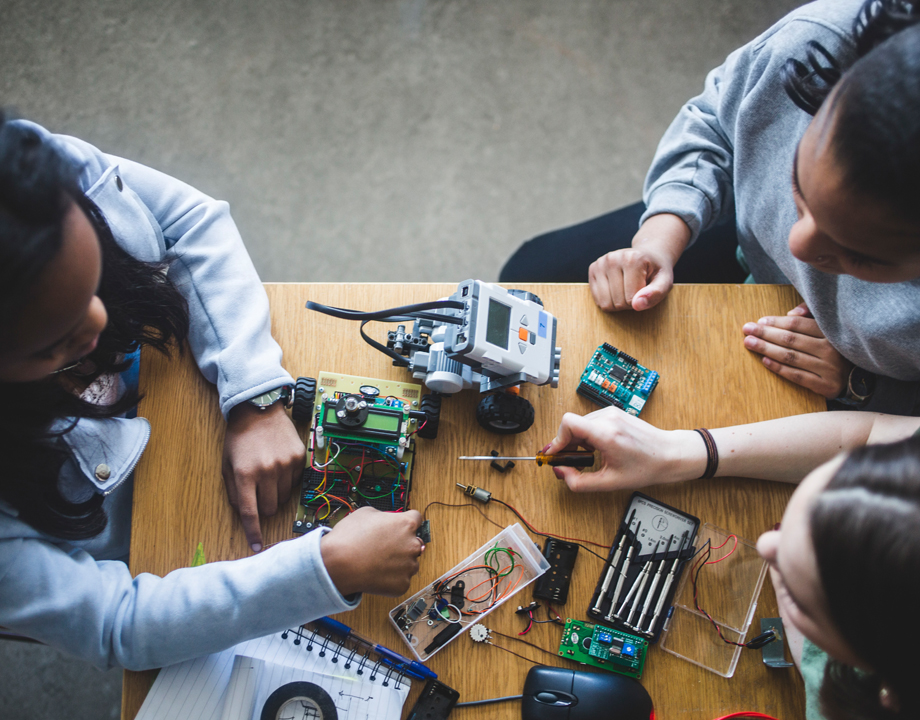

In her senior year at Brooklyn’s Pathway to Technology (P-Tech) Early College High School, ShuDon Brown was building a catapult from a bunch of wood pieces and other hodgepodge materials her robotics club members had amassed on the floor. The catapult was for New York’s annual pumpkin-throwing event, in which teams compete at flinging pumpkins as far as possible. Once the giant 10-foot machine was done, the team shuffled it to a nearby park for a test where they could throw pumpkins without breaking anything. Brown, who was also partaking in the Dress for Success day at the same time, was wearing high heels and a dress, but that didn’t stop her from testing their creation.

“It was the best project I ever worked on,” recalled Brown. “It was really fun to see it go from start to finish—build something from just a bunch of pieces scattered around the room.” P-Tech’s other projects, as well as classwork and teachers, were stimulating and engaging too. Brown graduated early with honors, received her Master’s in information technology at the age of 20, and was recently accepted into a Ph.D. program in education and leadership studies. She credits her initial “tech spark” to her high school, which was part of IBM’s science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, education initiative.

Over the past few years big corporations have been increasing their STEM efforts, supporting tech-savvy programs at schools, creating internship opportunities, and steering kids toward higher education. Companies have diverse reasons for implementing these programs, but there are common themes. Nearly all target the underrepresented youth, who don’t have the family resources to chart their path to a college degree. Many aim to create the future workforce to stay competitive in the 21st century. Some companies strive to get youngsters excited about STEM to recruit them as workers later. Others do it for the greater good—to create the next cohort of smart, talented people to solve society’s future problems.

IBM’s P-Tech schools aim to kill two birds with one stone—equip the undeserved youth with valuable job skills while also building qualified workforce the corporation or other companies may hire later. “Employers don't always find the right talent for their jobs so private enterprise works with educators to nurture the talent in competitive job roles,” said Grace Suh, IBM’s vice president of education. So it makes sense to start as early as high school.

“Students at P-Tech schools have up to six years to complete their high school diploma and their associate college degree at the same time,” Suh said, adding that the focus isn’t just on degrees, but practical skills. Students take college courses at their own pace, get mentors from the industry, and visit IBM sites. When they turn 16, they can attain paid internships with some of the program’s 600 partners, including GlobalFoundries, American Airlines, and Dow Chemicals, which can lead to full-time positions. IBM hires P-Tech graduates too.

Learn More with Our Infographic: Increasing Diversity in STEM

Unlike the traditional white or blue color positions, IBM calls them “new color jobs.” They include working on IBM’s Watson computer or doing front-end coding. IBM launched its first P-Tech school in Brooklyn in 2011, and now has 220 of them in 24 countries.

SAP, global software development company also believes that getting students interested in technology early is key. It follows the so-called three pillars—getting underrepresented youth excited about developing digital prowess; helping entrepreneurial minds build the necessary social and business skills; and connecting them with employers. To reach students, the company’s volunteers visit schools and community events.

“We have a really robust network of volunteers, so it’s not just us writing a check to run a program,” said Kate Morgan, SAP’s head of Corporate Social Responsibility in North America. “When volunteers work and engage with the students, they really get to know them and they go to bat for them.”

In North America, SAP operates early college programs in four schools—in Boston, New York, Oakland, and Vancouver. Schools partner with community colleges in the area, so that their curriculums are mapped to an associate degree the colleges offer. “That way students get community college credit while they are in high school,” said Morgan. “Academic work shows that when underrepresented youth get college credits while still in high schools, they have a lot more confidence and interest about going to college and finishing a degree.”

SAP also operates a Tech Summer program that offers paid internships for students partaking in the early college program. Those who are selected work in SAP’s local offices for eight weeks in summer, spending about 70 percent of their time on projects and the rest on their professional development. They get fully integrated into the teams, paired up with mentors, and build their networks within the company. Sometimes employees find interns so helpful they want to work with them again.

SAP assesses these programs’ achievements both in numbers, but also in more altruistic measures. Numbers are easy to cite—over 1,000 students are enrolled and approximately 200 SAP employees volunteer for the program. However, for the 200 students receiving college credits for free, the benefits are harder to calculate, but they are long-term. Without that high school-college link, they may not have been on the college track. “That’s changing the path of a family,” Morgan said. “We are really changing the way our teachers and students connect high school education and careers.”

Another piece of the puzzle is getting young kids interested in technical disciplines, said Peter Balyta, president of Texas Instruments’ Education Technology business. Balyta, who grew up in an immigrant family in Northern Canada, knows this firsthand. In school he preferred sports to technology—until an injury sparked his interest in physics. He became a motivated math and science teacher. “I was on a quest that no kid in my class ever thought that math was boring,” he said. Later he went to work for TI with a similar mission. He wanted to give every teacher the “cool tools” to inspire their students’ love of technical disciplines.

Math can be too abstract and repetitive to be exciting, Balyta said. Many students don’t see the point of graphing functions or repeating similar calculations 20 times. But if you present students with practical problems and cool tools to solve them, it can be a game changer. “The calculus and algebra can be too daunting, so kids switch their minds and curiosity elsewhere,” Balyta said. “If we can harness that curiosity and keep it in the classroom we can do better—but they need to see some practical applications for formulas, graphs, and charts.”

To spark kids’ curiosity in technology, TI STEM Squads have been travelling around the country teaching school students of various ages simple coding techniques. Using their TI calculators, students programmed TI-Innovator Rovers to do choreographed dances or navigated a robotic car around a 3D-printed city of the future. “At TI, we like to joke that we trick students into falling in love with math and science,” Balyta said. And the earlier you do it, the better.

Recommended for You: Does STEM Diversity Promote Workforce Diversity?

TI has a small summer high school internship program at its Dallas headquarters, which brings about 10 students from underserved areas of Texas to work with engineers to understand what they do. TI also works with college professors to integrate the company’s technology into the curriculum.

That feeds back to what the company expects as a return on investment. Every year TI hires 500 to 600 interns, 70 percent of who are eligible for an offer to join the company as college graduates (the rest still have to back to finish college.) Eighty percent of them accept the offer, Balyta said. The ROI from STEM squad teams is harder to put into numbers—and perhaps not even necessary because words make more sense. “STEM skills are surviving skills,” Balyta said. “Kids sitting in classrooms today will become tomorrow problem-solvers and leaders, who will have to implement solutions to our biggest challenges.”

Lisa Freed, STEM Program Manager at iRobot seconds the idea of attracting children to technology early. And the company has excellent robotic tools for the job. iRobot teams bring their models—Roomba, Root Robot, and Braava—to the classrooms, teaching children how to program them, in three different levels of difficulty. iRobot’s coding platform allows programming a simulated robot on a screen with a full virtual experience—and then transfer the features onto the physical robot. “When you show the students Roomba and they see how it can move and vacuum, it really brings it all to life,” said Freed.

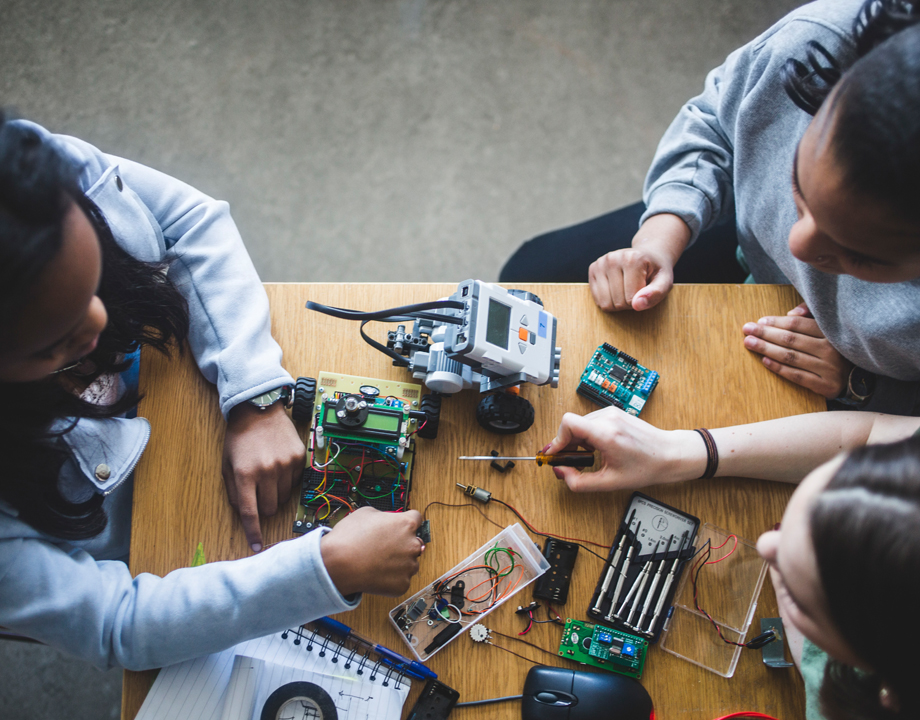

Many kids don't realize that just because they like to take things apart or build with Legos, they are budding mechanical engineers. Learning to program robots helps them realize these interests and picture themselves as future technologists. “Having to go from digital to physical with code is something really special,” said Zee Dubrovsky, iRobot’s education general manager and a mechanical engineer. “The appreciation of how your code interacts with the world around you makes you realize what you can do. And robots are one of the best things to take you on this journey.”

About 30 to 50 iRobot employees volunteer at schools. But aside of these numbers, iRobot doesn’t use other metrics to measure the outcomes. “We want to spark the interest in kids—and it’s hard to measure the sparks,” Zee said. Instead, the company relies on schools’ responses. So far, the schools had asked the team to come back with their robots every year—and that’s a telling sign.

Boeing can’t take its planes to a classroom, so instead the company brings school students of various ages on site visits. One of Boeing’s biggest programs, Dream Learners, brings over half a million kids to the company’s South Carolina facility to see how the planes are assembled. “We opened Dream Learners in 2010 to reach all five graders in the state,” said director of global engagement, Sam Whiting. “We now have 560 thousand students who come on site and learn from the team how to develop and create airplanes.” Similar programs operate at Boeing’s sites in Puget Sound, St. Lewis, and other locations. While they are primarily for middle and high school students, some also include upper elementary grades.

There are internship programs too. In 2016, Boeing hired 2,600 summer college interns in three different technical programs that ran 10 to 12 weeks. In the past few years, the company also ran several smaller high school internship programs, typically 10 to 50 students at a site. “They worked at our tanker program in Puget Sound or on the manufacturing floor in St Lewis,” Whiting said.

BMW is another company that invests in creating its own skilled workers. The company operates three different Service Technician Education Programs or STEP. One recruits technical school graduates with excellent credentials. The second, STEP apprenticeship, accepts employees already working at BMW dealerships. The third, M-STEP offers training for those discharged from the military and seeking career opportunities. The training runs for 16 weeks and is free, except for room and board if necessary.

Listen to ASME TechCast: Inspiring Young STEM Minds

The return on investment is huge for BMW, said Gary Uyematsu, the company’s national technical training manager. “Automotive technicians are very sought after and we need to fill almost 1000 positions a year in North America,” he said, adding that this demand will continue to grow. “As we sell more and more cars, we will need more and more technicians to maintain them.”

The access to the skilled workforce seems to be the universal challenge all companies have. And if this workforce isn’t created, future society will face serious issues—a shortage of people who will fix self-driving cars, fly supersonic planes, program the next generation of robots, and code the next-level AI. So to assure tech specialists’ existence tomorrow, companies are building their foundation today, starting early in the classroom. Or as Dubrovsky of iRobot, puts it, “We are trying to spark more sparks.” The society’s progress depends on it.

Lina Zeldovich is a writer based in Woodside, N.Y.

“It was the best project I ever worked on,” recalled Brown. “It was really fun to see it go from start to finish—build something from just a bunch of pieces scattered around the room.” P-Tech’s other projects, as well as classwork and teachers, were stimulating and engaging too. Brown graduated early with honors, received her Master’s in information technology at the age of 20, and was recently accepted into a Ph.D. program in education and leadership studies. She credits her initial “tech spark” to her high school, which was part of IBM’s science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, education initiative.

Over the past few years big corporations have been increasing their STEM efforts, supporting tech-savvy programs at schools, creating internship opportunities, and steering kids toward higher education. Companies have diverse reasons for implementing these programs, but there are common themes. Nearly all target the underrepresented youth, who don’t have the family resources to chart their path to a college degree. Many aim to create the future workforce to stay competitive in the 21st century. Some companies strive to get youngsters excited about STEM to recruit them as workers later. Others do it for the greater good—to create the next cohort of smart, talented people to solve society’s future problems.

Nurturing Talent

IBM’s P-Tech schools aim to kill two birds with one stone—equip the undeserved youth with valuable job skills while also building qualified workforce the corporation or other companies may hire later. “Employers don't always find the right talent for their jobs so private enterprise works with educators to nurture the talent in competitive job roles,” said Grace Suh, IBM’s vice president of education. So it makes sense to start as early as high school.

“Students at P-Tech schools have up to six years to complete their high school diploma and their associate college degree at the same time,” Suh said, adding that the focus isn’t just on degrees, but practical skills. Students take college courses at their own pace, get mentors from the industry, and visit IBM sites. When they turn 16, they can attain paid internships with some of the program’s 600 partners, including GlobalFoundries, American Airlines, and Dow Chemicals, which can lead to full-time positions. IBM hires P-Tech graduates too.

Learn More with Our Infographic: Increasing Diversity in STEM

Unlike the traditional white or blue color positions, IBM calls them “new color jobs.” They include working on IBM’s Watson computer or doing front-end coding. IBM launched its first P-Tech school in Brooklyn in 2011, and now has 220 of them in 24 countries.

SAP, global software development company also believes that getting students interested in technology early is key. It follows the so-called three pillars—getting underrepresented youth excited about developing digital prowess; helping entrepreneurial minds build the necessary social and business skills; and connecting them with employers. To reach students, the company’s volunteers visit schools and community events.

“We have a really robust network of volunteers, so it’s not just us writing a check to run a program,” said Kate Morgan, SAP’s head of Corporate Social Responsibility in North America. “When volunteers work and engage with the students, they really get to know them and they go to bat for them.”

In North America, SAP operates early college programs in four schools—in Boston, New York, Oakland, and Vancouver. Schools partner with community colleges in the area, so that their curriculums are mapped to an associate degree the colleges offer. “That way students get community college credit while they are in high school,” said Morgan. “Academic work shows that when underrepresented youth get college credits while still in high schools, they have a lot more confidence and interest about going to college and finishing a degree.”

SAP also operates a Tech Summer program that offers paid internships for students partaking in the early college program. Those who are selected work in SAP’s local offices for eight weeks in summer, spending about 70 percent of their time on projects and the rest on their professional development. They get fully integrated into the teams, paired up with mentors, and build their networks within the company. Sometimes employees find interns so helpful they want to work with them again.

SAP assesses these programs’ achievements both in numbers, but also in more altruistic measures. Numbers are easy to cite—over 1,000 students are enrolled and approximately 200 SAP employees volunteer for the program. However, for the 200 students receiving college credits for free, the benefits are harder to calculate, but they are long-term. Without that high school-college link, they may not have been on the college track. “That’s changing the path of a family,” Morgan said. “We are really changing the way our teachers and students connect high school education and careers.”

Sparking Curiosity

Another piece of the puzzle is getting young kids interested in technical disciplines, said Peter Balyta, president of Texas Instruments’ Education Technology business. Balyta, who grew up in an immigrant family in Northern Canada, knows this firsthand. In school he preferred sports to technology—until an injury sparked his interest in physics. He became a motivated math and science teacher. “I was on a quest that no kid in my class ever thought that math was boring,” he said. Later he went to work for TI with a similar mission. He wanted to give every teacher the “cool tools” to inspire their students’ love of technical disciplines.

Math can be too abstract and repetitive to be exciting, Balyta said. Many students don’t see the point of graphing functions or repeating similar calculations 20 times. But if you present students with practical problems and cool tools to solve them, it can be a game changer. “The calculus and algebra can be too daunting, so kids switch their minds and curiosity elsewhere,” Balyta said. “If we can harness that curiosity and keep it in the classroom we can do better—but they need to see some practical applications for formulas, graphs, and charts.”

To spark kids’ curiosity in technology, TI STEM Squads have been travelling around the country teaching school students of various ages simple coding techniques. Using their TI calculators, students programmed TI-Innovator Rovers to do choreographed dances or navigated a robotic car around a 3D-printed city of the future. “At TI, we like to joke that we trick students into falling in love with math and science,” Balyta said. And the earlier you do it, the better.

Recommended for You: Does STEM Diversity Promote Workforce Diversity?

TI has a small summer high school internship program at its Dallas headquarters, which brings about 10 students from underserved areas of Texas to work with engineers to understand what they do. TI also works with college professors to integrate the company’s technology into the curriculum.

That feeds back to what the company expects as a return on investment. Every year TI hires 500 to 600 interns, 70 percent of who are eligible for an offer to join the company as college graduates (the rest still have to back to finish college.) Eighty percent of them accept the offer, Balyta said. The ROI from STEM squad teams is harder to put into numbers—and perhaps not even necessary because words make more sense. “STEM skills are surviving skills,” Balyta said. “Kids sitting in classrooms today will become tomorrow problem-solvers and leaders, who will have to implement solutions to our biggest challenges.”

Lisa Freed, STEM Program Manager at iRobot seconds the idea of attracting children to technology early. And the company has excellent robotic tools for the job. iRobot teams bring their models—Roomba, Root Robot, and Braava—to the classrooms, teaching children how to program them, in three different levels of difficulty. iRobot’s coding platform allows programming a simulated robot on a screen with a full virtual experience—and then transfer the features onto the physical robot. “When you show the students Roomba and they see how it can move and vacuum, it really brings it all to life,” said Freed.

Many kids don't realize that just because they like to take things apart or build with Legos, they are budding mechanical engineers. Learning to program robots helps them realize these interests and picture themselves as future technologists. “Having to go from digital to physical with code is something really special,” said Zee Dubrovsky, iRobot’s education general manager and a mechanical engineer. “The appreciation of how your code interacts with the world around you makes you realize what you can do. And robots are one of the best things to take you on this journey.”

About 30 to 50 iRobot employees volunteer at schools. But aside of these numbers, iRobot doesn’t use other metrics to measure the outcomes. “We want to spark the interest in kids—and it’s hard to measure the sparks,” Zee said. Instead, the company relies on schools’ responses. So far, the schools had asked the team to come back with their robots every year—and that’s a telling sign.

Future Workforce

Boeing can’t take its planes to a classroom, so instead the company brings school students of various ages on site visits. One of Boeing’s biggest programs, Dream Learners, brings over half a million kids to the company’s South Carolina facility to see how the planes are assembled. “We opened Dream Learners in 2010 to reach all five graders in the state,” said director of global engagement, Sam Whiting. “We now have 560 thousand students who come on site and learn from the team how to develop and create airplanes.” Similar programs operate at Boeing’s sites in Puget Sound, St. Lewis, and other locations. While they are primarily for middle and high school students, some also include upper elementary grades.

There are internship programs too. In 2016, Boeing hired 2,600 summer college interns in three different technical programs that ran 10 to 12 weeks. In the past few years, the company also ran several smaller high school internship programs, typically 10 to 50 students at a site. “They worked at our tanker program in Puget Sound or on the manufacturing floor in St Lewis,” Whiting said.

BMW is another company that invests in creating its own skilled workers. The company operates three different Service Technician Education Programs or STEP. One recruits technical school graduates with excellent credentials. The second, STEP apprenticeship, accepts employees already working at BMW dealerships. The third, M-STEP offers training for those discharged from the military and seeking career opportunities. The training runs for 16 weeks and is free, except for room and board if necessary.

Listen to ASME TechCast: Inspiring Young STEM Minds

The return on investment is huge for BMW, said Gary Uyematsu, the company’s national technical training manager. “Automotive technicians are very sought after and we need to fill almost 1000 positions a year in North America,” he said, adding that this demand will continue to grow. “As we sell more and more cars, we will need more and more technicians to maintain them.”

The access to the skilled workforce seems to be the universal challenge all companies have. And if this workforce isn’t created, future society will face serious issues—a shortage of people who will fix self-driving cars, fly supersonic planes, program the next generation of robots, and code the next-level AI. So to assure tech specialists’ existence tomorrow, companies are building their foundation today, starting early in the classroom. Or as Dubrovsky of iRobot, puts it, “We are trying to spark more sparks.” The society’s progress depends on it.

Lina Zeldovich is a writer based in Woodside, N.Y.