The Best of Both Worlds for Robotic Swarms

The Best of Both Worlds for Robotic Swarms

Using the central nervous system as inspiration, researchers from Université Libre de Bruxelles have developed a hybrid approach to programming self-organizing groups of robots.

As the old saying goes, there’s safety in numbers.

Different animal species, from bees to birds, instinctually come together as groups, or swarms, to create one large entity that better protects individuals from predators. But this collective behavior does more than act as a security system for certain insects and animals. Swarms also facilitate more complex behaviors like distributed sensing and detecting new food sources.

Over the past decade, roboticists have looked at finding ways to program robot swarms to monitor pollution in the Earth’s waterways or even detect survivors in an earthquake or other emergency scenario. To date, researchers have programmed such swarms to self-organize using simple, local interactions between individual robots and their nearest neighbors. Mary Katherine Heinrich, a postdoctoral researcher at the IRIDIA artificial intelligence laboratory at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) in Belgium, said that approach was undertaken to leverage the “practical advantages with self-organization,” like scalability, flexibility, fault tolerance, and the ability to avoid a single point of failure.

“In the past decades, swarm robotics research has demonstrated a wide range of powerful collective behaviors that do not require any central coordinating entity or process,” she explained. “However, despite some progress, robot swarms have still struggled to transition from laboratory experiments to real-world applications.”

This, Heinrich said, is because of the main disadvantage inherent to self-organization designs—each robot is programmed individually to produce the desired behavior at the group level.

“This makes swarm behaviors difficult or impossible to design analytically,” said Marco Dorigo, director of the IRIDIA lab. “Developing new swarm behaviors is a time-consuming trial-and-error process and once new swarm behaviors have been developed, they cannot be easily modified or combined.”

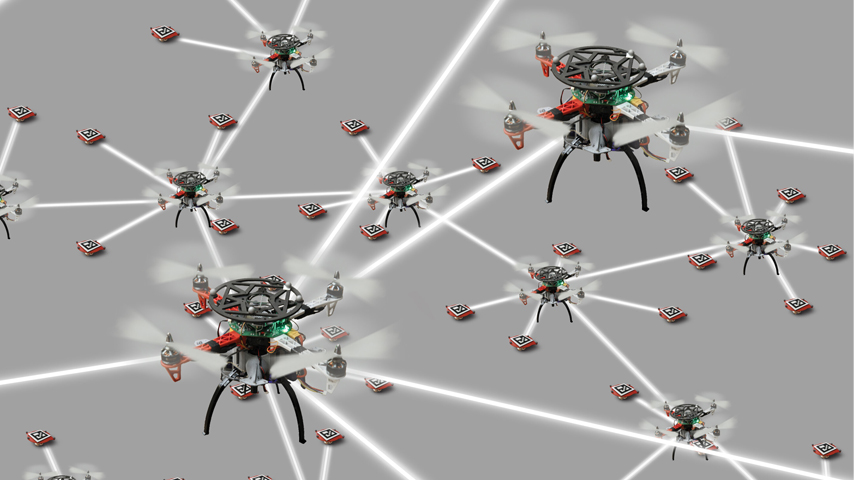

To address this issue, Heinrich, Dorigo, and colleagues decided to combine some aspects of centralized control with more conventional robotic swarm designs with the goal of harnessing the benefits of both in one unified system. The inspiration for their design was the human nervous system, a system they refer to as a self-organizing nervous system (SoNS).

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

“SoNS provides a general framework for constructing and reconstructing a self-organizing hierarchy [with the robots],” Heinrich said. “Robots can self-organize a dynamic, ad hoc control network in which they temporarily and interchangeably occupy certain positions in a leadership hierarchy, including the highest hierarchy position, a ‘brain’ position.”

Like other types of swarm programming, each robot communicates only with its direct neighbors. This avoids potential bottlenecks in communication that might be found in a system that has a fully centralized control design. Instead, depending on the task at hand, each robot can pass sensor information, merging the data with that from other neighbors, as it is passed up to the “brain,” and control information can be unmerged as it is passed down to the collective. This, Dorigo said, allows for a balance of individual versus collective behaviors that can be better managed.

“SoNS works as a kind of middleware for robots to self-organize temporary, dynamic hierarchies with their peers, providing robot swarms with some useful functionalities,” he said. “Using SoNS, robots can coordinate their collective sensing, actuation, and decision-making activities in a locally centralized way, without sacrificing scalability, flexibility, and fault tolerance. In other words, SoNS effectively allows a robot warm to be programmed as if it were a single robot, which we believe can greatly improve the transferability of robot swarms from laboratory environments to real-world applications.”

The research team tested their system design with a heterogenous group of aerial and ground robots—both in simulated and real-world scenarios. They used several different mission types, including basic, binary decision making and a more complex search and rescue paradigm. The results showed that SoNS could allow the robots to successfully complete all experimental test missions. Dorigo and colleagues then took their tests a step further, testing the limits of SoNS’ scalability using up to 250 robots in simulation.

More for You: Simple Instructions Make a Robot Swarm

“The scalability results showed that SoNS, in its current version, is fully reliable up to 125 robots, somewhat stable up to 220 robots, but performance degrades substantially in systems larger than 220 robots,” he said. “Future work could explore scalability beyond these system sizes by combining SoNS with more advanced formation control approaches, instead of simple reactive control.”

In addition, the group plans to develop more advanced SoNS’ “brains,” as well as more advanced hierarchical computation, which could allow future swarms to perform online learning or autonomous mission planning in the future. In the meantime, however, Heinrich said the SoNS approach demonstrates the power of going beyond simple self-organization or central control programs for robotic swarms.

“For multi-robot systems, the SoNS approach aims to combine the most useful aspects of self-organized control with the most useful aspects of centralized control,” she said. “This can be pertinent to engineers seeking to harness the benefits of both in one unified system.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston.