The Disneyland Monorail's Mark on Transit

The Disneyland Monorail's Mark on Transit

Named an ASME Landmark in 1986, the Disneyland Monorail was the first of its kind to launch in the United States.

Since opening in 1959, the Disneyland Monorail has been carrying passengers around the theme park daily. It was based on a German monorail developed by Axel Wenner-Gren of the Alweg Company, but came together in a far more unusual way, when compared to other transit projects.

ASME recognizes engineering landmarks based on their innovation and impact, honoring the Disneyland Monorail in 1986 as a historically important work, for its contribution to the evolution of mechanical engineering and its influence on society.

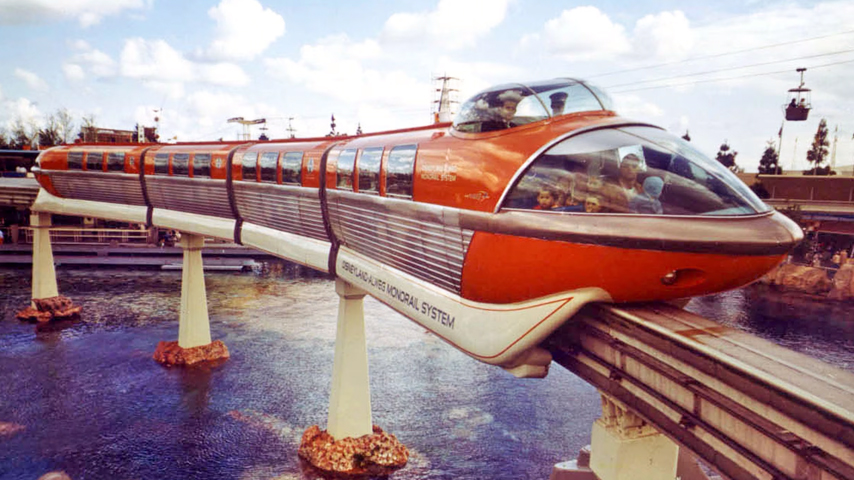

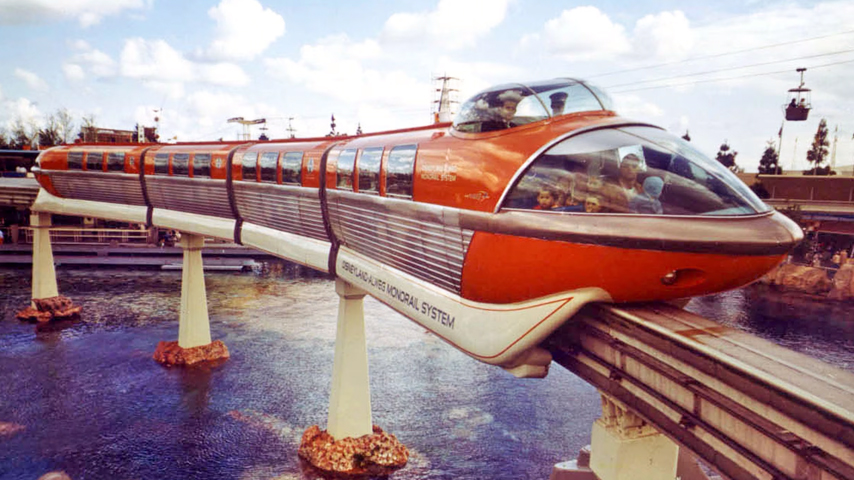

“One of the things that sets the Disneyland Monorail apart from the other ones is the vehicle design. There have been a number of iterations, but they’ve all kind of had this retro future feel,” said Todd James Pierce, an author, professor at Cal Poly University, and host of the DHI podcast that discusses the history of animation and theme park development. “I think that’s one of the touchstones of the experiences at the parks is that there are things that you understand and that you relate to and they’re familiar, but they’re also unique to being there.”

In fact, Disney Legend and Imagineer Robert Gurr, who designed the Disneyland Monorail, said, “If you look at that train close, that’s a 1938 Buck Rogers comic strip.”

But the reason Disneyland even has a monorail is that in 1952, Walt Disney wrote it down as one of the elements he would like to have if he were to ever build a theme park, Gurr recalled. Fast forward to the summer of 1958, when Disney and his wife were driving near Cologne, Germany, and a monorail happened to zip across the street in front of them.

Immediately, Disney sought out the local firm behind that monorail, Alweg Company, and even though he ran into a language barrier, was able to secure documents and photographs of the system. Disney then immediately sent one of his vice presidents to Alweg to discuss a business structure, which followed shortly thereafter with a plan to build a monorail at Disneyland in summer 1959—in less than a year’s time.

"Walt had all this information that he brought to me one day at a meeting between him, my immediate boss, who was head of the Disney machine shop at the Disney studio, and explained that we’re going to get started on a monorail,” Gurr said. That was mid-October 1958.

Alweg sent two of their engineers over from Germany to work with Disney’s structural engineers to design the beamway, a concrete structure made of precast steel-framed I-section girders.

“Walt also supplied me with the basic dimensions of this beamway with respect to a vehicle that would go on it, the plan view, and the minimum turn radius,” Gurr added. “In this case it was 118 feet, which is pretty doggone tight.”

The original beamway would stretch eight-tenths of a mile around Tomorrowland and featured 7 percent grades. It was just 20 inches wide and 34.5 inches high. In the years that followed, the monorail eventually expanded to travel about 2.5 miles around the park.

Another ASME Landmark: Evinrude Outboard Motors Changed Summer Forever

"So, with that information in hand, Walt looks at me and says, ‘Bobby, I want you to get started on our design right away.’ And he walks out of the room. There is no team at that moment,” Gurr recalled with a laugh.

Within several days, Gurr figured out the train’s dimensions, then its appearance, having drawn everything out at his kitchen table at home, and that was the design they ran with—no other shape was even considered.

“In other words, we had no committee, we had no input, we had no competition of designers, no production notes from the corporation, nothing. I had a white piece of paper and I had a pencil, and that’s all that was necessary,” he said. "I never gave it a thought at that time, but in hindsight it was, holy moly, that is not the way industry works—but that’s the way Walt worked. And to me it was logical at the time because he’d always said, ‘Bobby, I’d like to get you started on something.’ And he gave me a 100 percent freedom. And I’d probably done maybe 20 projects or so by that time in that manner.”

By the end of his nearly 40-year career at Disney, Gurr would design more than 100 attractions across the company’s various theme parks.

Other monorail systems existed at the time, such as the German Wuppertal train and the French SAFEGE system, both of which hung below their beams. Disney rode those and realized that they weren’t the way to go for Disneyland.

Alweg’s test monorail had been operating on a one-mile stretch in Cologne since 1952. Its design, formally known as the German saddlebag, looked “sort of like a loaf of bread with a slot on the bottom, sitting on a stick,” Gurr described.

That test system was developed by Alweg founder Axel Wenner-Gren, a Swedish engineer who was unable to take the money he had in Germany out of the country after World War II. So instead, he put that money toward developing a monorail.

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

His German saddlebag configuration ended up being the best choice for monorails—not just for the Disneyland iteration, but ever since. “Nobody seems to come up with a better one,” Gurr said.

Disneyland’s iteration ended up being about an 80 percent scaled version of the original German line, Pierce said. The monorail that was eventually built at Disneyworld in Florida in 1971 was a full-sized version.

While construction of the beamway’s structure progressed, work on the trains required a bit of help from the studio’s machine shop, both from the mechanical group and the electrical group.

Gurr, who was around 27 at that point, was inspired by the hot rod society in which he grew up. So instead of trying to build every piece of the monorail trains from scratch, it became a matter of combining elements from various places.

First was the electrical propulsion system, which actually came from a PCC (Presidents’ Conference Committee) streetcar, a system that has been around since the 1930s and is still in use today in places like San Francisco.

That meant a lot of used electrical systems would probably be lying around in junkyards, which is exactly where the electrical team ended up purchasing electrical sets from old PCC cars to use on the monorail. Meanwhile, four 600 Volt D.C. 100 horsepower electric motors power each train for a max running speed of 35 miles per hour. Those are supplied by a 600-volt direct current that moves through two copper and steel busbars that are mounted onto the beam’s right side.

For the tires that would run along the top of the beamway, Gurr was inspired by drag racers who take large differentials and cut them down to short stub axles. He realized that he could do the same thing but keep an axle on just one side. “Now I have a 90-degree gearbox. Now I have a drive shaft that will connect to the motor. So, you see how you can engineer without engineering anything,” he said.

Each of the monorail’s trains features 10 vertical pneumatic tires that carry the vehicle load on the elevated beamway. Another 40 pneumatic tires, smaller ones for this purpose, run horizontally along the I-shaped beam for stability, along with four guiding wheels.

The train’s structure was the next consideration: The chassis was configured like a railroad car with a frame, then at either end was a bogie upon which the train car sat.

"And then I thought because of this very tight radius, I would make it like the Spanish Talgo train—you have a bogie on one end and a pivot ball joint on the other end, so it's like a bunch of elephants walking together, each grabs the tail of the other one. It's a very simple system,” Gurr said.

To manufacture the trains, Gurr's supervisor at the machine shop, Roger Broggie, made a contract with a local garbage truck company. But as it turned out, their project management skills on high-speed jobs were lacking.

When it became obvious that the trains wouldn’t be done in time, Broggie had everything moved to sound stage three, “with all the tooling and partially constructed trains. And my boss Roger says, ‘Robert, you now are in charge of the manufacture, but don’t stop designing it,’” Gurr said.

So, Disney crews continued assembly, from the major chassis to the power components and sheet metal comprising the exterior. Compound curved steel sheet forms for the front end came from California Metal Shaping, which built and restored classic cars. For the windshield, the team created a wooden form covered with table felt, dropped by Planet Plastics and had a windshield vacuum formed.

Over the Rails: 5 Countries Where Trains Are Fastest

The Disneyland Monorail initially had two trains, one red (which was delivered first) and one blue.

“We’re ready to go two weeks before the opening day, but the electrical department hooked up the motors backwards,” Gurr recalled. “The train moved an eighth of an inch when I first applied the power and then broke the drive shafts.”

He worked nonstop for the next two weeks to fix the failures, and after much troubleshooting, the monorail was finally able to travel around the beamway for an entire lap without breaking down.

With the significant time crunch between the breakdown and the monorail’s launch on June 14, 1959, there wasn’t time to train either the monorail supervisor or any ride operators. The Disney costume department made Gurr a monorail cast member uniform overnight so that he could run the monorail on launch.

“By opening day, we’re ready to go. Here comes Richard Nixon, vice president of the United States, Secret Service, Walt, couple of friends, the family, and they want to see the monorail in the morning hours before we're going to dedicate it," Gurr recalled. “Walt wants me to give Nixon a ride, which we do. I didn't know what the train was going to do because it only worked one time the night before. But I drove the train—I drove the train until nine that night and I finally got somebody trained so I could go home.”

In the months that followed, Walt Disney invited leadership from various cities to view the monorail to try and spread interest about the system. No one was interested.

Although Alweg set up a location in Los Angeles to try and sell the monorail system, it never took off either. But the monorail did gain more of a footing elsewhere in the world. Today, Japan is home to nearly a dozen monorail systems, the most in the world. Other Asian countries have embraced monorail as well, with another dozen or so scattered across the region.

“It’s a little bit like Jules Vern. Jules Vern’s idea of the future from the 1800s is not really how the future turned out, but it's a very imaginative concept of what the future might have been. And that I think inspired future dreamers and future engineers to invent new things that were based on these prototypes or these visions for what the future might have been, even if it didn't turn out that way,” Pierce said. “And so monorails now, in my mind, are mostly associated with fairs and amusement parks, but that wasn't their original purpose. It's kind of like a museum piece to what the future might have been in some ways.”

In the more than 60 years since the Disneyland Monorail opened, it’s been rebuilt, repaired, and replaced, but the basic structural configuration remains the same as that original version—albeit rearranged slightly, Gurr said.

As for the success of the monorail at Disney parks—not just in North America but also at various international locations—Gurr credits the system’s “spectacular futuristic look.”

“It inspired the public, but it did not inspire American cities. But the monorail remains a good-looking dream,” he said. “Whenever I’m on the monorail platform at Disney, I do point out the ASME plaque that we’ve got there. I remember that evening—I thought when I went down there that night, wow, I've designed a train that is now recognized as an engineering landmark. But it never went anywhere. It’s just the way history worked.”

Louise Poirier is senior editor.

ASME recognizes engineering landmarks based on their innovation and impact, honoring the Disneyland Monorail in 1986 as a historically important work, for its contribution to the evolution of mechanical engineering and its influence on society.

“One of the things that sets the Disneyland Monorail apart from the other ones is the vehicle design. There have been a number of iterations, but they’ve all kind of had this retro future feel,” said Todd James Pierce, an author, professor at Cal Poly University, and host of the DHI podcast that discusses the history of animation and theme park development. “I think that’s one of the touchstones of the experiences at the parks is that there are things that you understand and that you relate to and they’re familiar, but they’re also unique to being there.”

In fact, Disney Legend and Imagineer Robert Gurr, who designed the Disneyland Monorail, said, “If you look at that train close, that’s a 1938 Buck Rogers comic strip.”

But the reason Disneyland even has a monorail is that in 1952, Walt Disney wrote it down as one of the elements he would like to have if he were to ever build a theme park, Gurr recalled. Fast forward to the summer of 1958, when Disney and his wife were driving near Cologne, Germany, and a monorail happened to zip across the street in front of them.

Immediately, Disney sought out the local firm behind that monorail, Alweg Company, and even though he ran into a language barrier, was able to secure documents and photographs of the system. Disney then immediately sent one of his vice presidents to Alweg to discuss a business structure, which followed shortly thereafter with a plan to build a monorail at Disneyland in summer 1959—in less than a year’s time.

"Walt had all this information that he brought to me one day at a meeting between him, my immediate boss, who was head of the Disney machine shop at the Disney studio, and explained that we’re going to get started on a monorail,” Gurr said. That was mid-October 1958.

Solo start

Alweg sent two of their engineers over from Germany to work with Disney’s structural engineers to design the beamway, a concrete structure made of precast steel-framed I-section girders.

“Walt also supplied me with the basic dimensions of this beamway with respect to a vehicle that would go on it, the plan view, and the minimum turn radius,” Gurr added. “In this case it was 118 feet, which is pretty doggone tight.”

The original beamway would stretch eight-tenths of a mile around Tomorrowland and featured 7 percent grades. It was just 20 inches wide and 34.5 inches high. In the years that followed, the monorail eventually expanded to travel about 2.5 miles around the park.

Another ASME Landmark: Evinrude Outboard Motors Changed Summer Forever

"So, with that information in hand, Walt looks at me and says, ‘Bobby, I want you to get started on our design right away.’ And he walks out of the room. There is no team at that moment,” Gurr recalled with a laugh.

Within several days, Gurr figured out the train’s dimensions, then its appearance, having drawn everything out at his kitchen table at home, and that was the design they ran with—no other shape was even considered.

“In other words, we had no committee, we had no input, we had no competition of designers, no production notes from the corporation, nothing. I had a white piece of paper and I had a pencil, and that’s all that was necessary,” he said. "I never gave it a thought at that time, but in hindsight it was, holy moly, that is not the way industry works—but that’s the way Walt worked. And to me it was logical at the time because he’d always said, ‘Bobby, I’d like to get you started on something.’ And he gave me a 100 percent freedom. And I’d probably done maybe 20 projects or so by that time in that manner.”

By the end of his nearly 40-year career at Disney, Gurr would design more than 100 attractions across the company’s various theme parks.

Drawing inspiration

Other monorail systems existed at the time, such as the German Wuppertal train and the French SAFEGE system, both of which hung below their beams. Disney rode those and realized that they weren’t the way to go for Disneyland.

Alweg’s test monorail had been operating on a one-mile stretch in Cologne since 1952. Its design, formally known as the German saddlebag, looked “sort of like a loaf of bread with a slot on the bottom, sitting on a stick,” Gurr described.

That test system was developed by Alweg founder Axel Wenner-Gren, a Swedish engineer who was unable to take the money he had in Germany out of the country after World War II. So instead, he put that money toward developing a monorail.

Become a Member: How to Join ASME

His German saddlebag configuration ended up being the best choice for monorails—not just for the Disneyland iteration, but ever since. “Nobody seems to come up with a better one,” Gurr said.

Disneyland’s iteration ended up being about an 80 percent scaled version of the original German line, Pierce said. The monorail that was eventually built at Disneyworld in Florida in 1971 was a full-sized version.

A mish-mash

While construction of the beamway’s structure progressed, work on the trains required a bit of help from the studio’s machine shop, both from the mechanical group and the electrical group.

Gurr, who was around 27 at that point, was inspired by the hot rod society in which he grew up. So instead of trying to build every piece of the monorail trains from scratch, it became a matter of combining elements from various places.

First was the electrical propulsion system, which actually came from a PCC (Presidents’ Conference Committee) streetcar, a system that has been around since the 1930s and is still in use today in places like San Francisco.

That meant a lot of used electrical systems would probably be lying around in junkyards, which is exactly where the electrical team ended up purchasing electrical sets from old PCC cars to use on the monorail. Meanwhile, four 600 Volt D.C. 100 horsepower electric motors power each train for a max running speed of 35 miles per hour. Those are supplied by a 600-volt direct current that moves through two copper and steel busbars that are mounted onto the beam’s right side.

For the tires that would run along the top of the beamway, Gurr was inspired by drag racers who take large differentials and cut them down to short stub axles. He realized that he could do the same thing but keep an axle on just one side. “Now I have a 90-degree gearbox. Now I have a drive shaft that will connect to the motor. So, you see how you can engineer without engineering anything,” he said.

Each of the monorail’s trains features 10 vertical pneumatic tires that carry the vehicle load on the elevated beamway. Another 40 pneumatic tires, smaller ones for this purpose, run horizontally along the I-shaped beam for stability, along with four guiding wheels.

The train’s structure was the next consideration: The chassis was configured like a railroad car with a frame, then at either end was a bogie upon which the train car sat.

"And then I thought because of this very tight radius, I would make it like the Spanish Talgo train—you have a bogie on one end and a pivot ball joint on the other end, so it's like a bunch of elephants walking together, each grabs the tail of the other one. It's a very simple system,” Gurr said.

Assembly required

To manufacture the trains, Gurr's supervisor at the machine shop, Roger Broggie, made a contract with a local garbage truck company. But as it turned out, their project management skills on high-speed jobs were lacking.

When it became obvious that the trains wouldn’t be done in time, Broggie had everything moved to sound stage three, “with all the tooling and partially constructed trains. And my boss Roger says, ‘Robert, you now are in charge of the manufacture, but don’t stop designing it,’” Gurr said.

So, Disney crews continued assembly, from the major chassis to the power components and sheet metal comprising the exterior. Compound curved steel sheet forms for the front end came from California Metal Shaping, which built and restored classic cars. For the windshield, the team created a wooden form covered with table felt, dropped by Planet Plastics and had a windshield vacuum formed.

Over the Rails: 5 Countries Where Trains Are Fastest

The Disneyland Monorail initially had two trains, one red (which was delivered first) and one blue.

“We’re ready to go two weeks before the opening day, but the electrical department hooked up the motors backwards,” Gurr recalled. “The train moved an eighth of an inch when I first applied the power and then broke the drive shafts.”

He worked nonstop for the next two weeks to fix the failures, and after much troubleshooting, the monorail was finally able to travel around the beamway for an entire lap without breaking down.

Launching a landmark

With the significant time crunch between the breakdown and the monorail’s launch on June 14, 1959, there wasn’t time to train either the monorail supervisor or any ride operators. The Disney costume department made Gurr a monorail cast member uniform overnight so that he could run the monorail on launch.

“By opening day, we’re ready to go. Here comes Richard Nixon, vice president of the United States, Secret Service, Walt, couple of friends, the family, and they want to see the monorail in the morning hours before we're going to dedicate it," Gurr recalled. “Walt wants me to give Nixon a ride, which we do. I didn't know what the train was going to do because it only worked one time the night before. But I drove the train—I drove the train until nine that night and I finally got somebody trained so I could go home.”

In the months that followed, Walt Disney invited leadership from various cities to view the monorail to try and spread interest about the system. No one was interested.

Although Alweg set up a location in Los Angeles to try and sell the monorail system, it never took off either. But the monorail did gain more of a footing elsewhere in the world. Today, Japan is home to nearly a dozen monorail systems, the most in the world. Other Asian countries have embraced monorail as well, with another dozen or so scattered across the region.

“It’s a little bit like Jules Vern. Jules Vern’s idea of the future from the 1800s is not really how the future turned out, but it's a very imaginative concept of what the future might have been. And that I think inspired future dreamers and future engineers to invent new things that were based on these prototypes or these visions for what the future might have been, even if it didn't turn out that way,” Pierce said. “And so monorails now, in my mind, are mostly associated with fairs and amusement parks, but that wasn't their original purpose. It's kind of like a museum piece to what the future might have been in some ways.”

In the more than 60 years since the Disneyland Monorail opened, it’s been rebuilt, repaired, and replaced, but the basic structural configuration remains the same as that original version—albeit rearranged slightly, Gurr said.

As for the success of the monorail at Disney parks—not just in North America but also at various international locations—Gurr credits the system’s “spectacular futuristic look.”

“It inspired the public, but it did not inspire American cities. But the monorail remains a good-looking dream,” he said. “Whenever I’m on the monorail platform at Disney, I do point out the ASME plaque that we’ve got there. I remember that evening—I thought when I went down there that night, wow, I've designed a train that is now recognized as an engineering landmark. But it never went anywhere. It’s just the way history worked.”

Louise Poirier is senior editor.