Using Microfluidics to Diagnose HIV

Using Microfluidics to Diagnose HIV

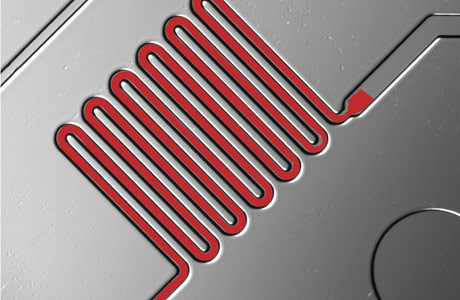

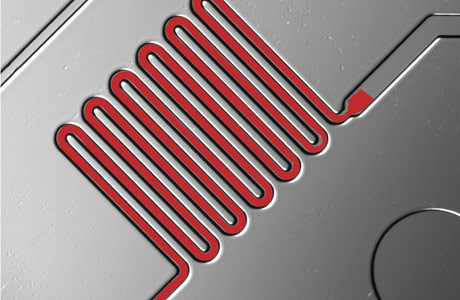

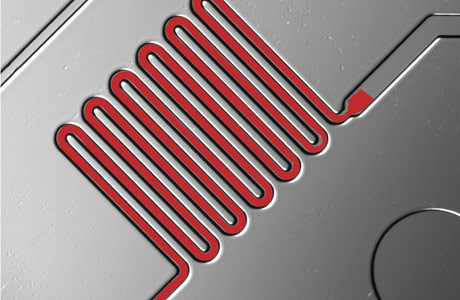

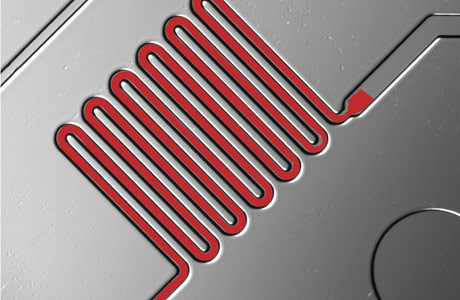

Blood is drawn through microfluidic channels where reagents identify disease molecules.

In 2010, Samuel K. Sia wrapped up five years of developing and field testing a novel microfluidic device that promises to simply and quickly diagnose HIV and other diseases in rural, isolated regions of the developing world. That may have been the easy part. Sia, an associate biomedical professor at Columbia University, New York, is now trying to garner commercial interest–and money–to get the device to market and he expects it will be a tough slog.

"For a product in the U.S. or Europe, that task is taken up by industry," says Sia. "Unfortunately [the process] is missing for things like global health. Investors don't [look for] products in the developing world. The payback is not there."

Lab on a Chip

Sia's product is called the mChip, for mobile microfluidic chip. About the size of a credit card, it is produced through injection molding and holds a series of channels fitted with chemicals and nanoparticles that work to identify diseases from just one drop of blood. And it works fast. In just 15 to 20 minutes, the health-care provider can read the results by eye or with a battery-powered diagnostic "reader" developed to interpret the results.

Sia says the mChip's impact will be felt most in isolated areas where people have limited access to any health care, such as Rwanda, where the device was tested. Standard practice calls for drawing blood in a local clinic and sending the results to a national laboratory. Turnaround time is often days or weeks and many people who sometimes live days away from a clinic are unlikely to travel back there to get results.

The mChip provides fast, accurate diagnosis, allowing the health-care provider to even begin treatment on the spot. The chip was successfully used in Rwanda to diagnose HIV and syphilis. Sia says the test is especially important for pregnant women, who risk passing disease to their unborn child. Making a diagnosis even more efficient, Sia and his team recently implanted a communications chip within the mChip, allowing transfer and access to a patient's electronic health records.

Sia first broached the idea in 2001 when living in Togo while working toward his Ph.D. "I wasn't doing microfluidics at the time," he says. But not having a bias toward any one technology helped him in devising what became the mChip.

Tools

He started with proven existing blood-testing procedures and worked to shrink them down. "The process is really scalable and really cheap," he says. "It is similar to a glucose test for a diabetic patient. Microfluidics is really just a tool in moving tiny amounts of fluid around. It certainly made sense in shrinking down blood volume and chemical reagents."

In 2004, Sia and colleagues also formed an independent venture-backed company, Claros Diagnostics Inc., Woburn, MA., to produce the chip. They've had success in producing and marketing a similar product to diagnose prostate cancer that now is approved for use in the European Union and is being reviewed in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration. The prostate detection chip paved the way for development of the HIV project and works on the same principles.

Requiring only a microliter of blood, the chip is produced with nanoscale features. Each chip has seven channels, looped in various ways, that hold reagents and markers that identify targeted molecules. Multiple channels allow different tests to be performed on the same chip. A vacuum, usually a syringe, draws the blood and reagents through the channels. Gold and silver nano particles will attach to the appropriate molecule and provide the color to interpret the tests. The entire process takes only 15-20 minutes.

Although gold and silver can be expensive, they are used in such small quantities that costs are able to be kept down. The manufacturing process has been refined to the point that plastic chips cost mere pennies. Sia says total costs for an HIV/syphilis chip, including chemical reagents, top out at three to four dollars, and the diagnostic reader is another $100.

Next Challenge

Bringing a fast, accurate, and inexpensive testing option to market "is a very solvable problem," says Sia. "It is not like trying to come up with an HIV vaccine, for instance. It is a bounded engineering problem." Sia's lab also is working on tests for hepatitis, malaria, and herpes. Although the tests were developed for use in poor, developing countries, the prostate test being marketed to developed countries may provide the boost to get the HIV test to market.

"There's more than enough 'proof of concept' [products] out there," says Sia. "This is a convenient technology, but this isn't just about the technology, but getting it all to market. There isn't a good process for this. We hope that we're not going to be talking about this for another 10 years."

Listen to a brief podcast with Samuel Sia.

Bringing a fast, accurate and inexpensive testing option to market "is a very solvable problem," says Sia. "It is not like trying to come up with an HIV vaccine, for instance. It is a bounded engineering problem.