When to Teach a Robot

When to Teach a Robot

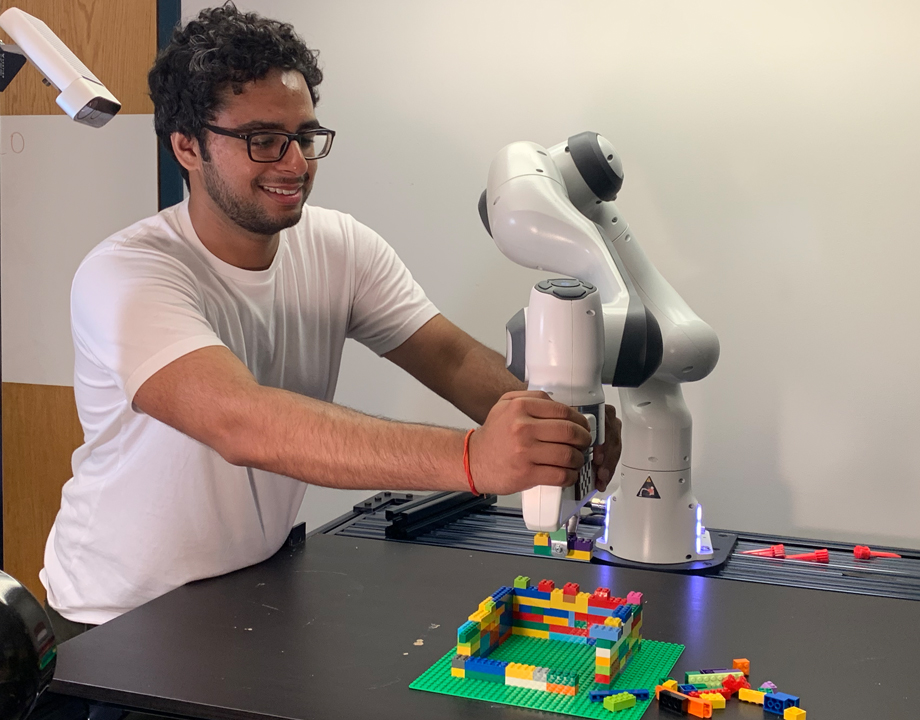

CMU grad student Shivam Vats displays robot task determined by algorithm. Photo: Carnegie Mellon University.

The employment rate is up for robots. More and more humans in the manufacturing arena are working side by side with colleagues that lack DNA. While it’s undoubtedly a boon to get a little help from tireless automatons, one important question must be solved to use both humans and robots as efficiently as possible: Who’s going to do what?

Now researchers out of Carnegie Melon have created an algorithm to help answer that. question

When robots are programmed to do a single a task and repeat it for months, or years, on end, that question isn’t so hard to answer. The robots simply do the repetitive job they were designed for—there’s nothing to figure out when a machine’s capabilities are fixed. But now robots can be taught to do new jobs on the fly and their flesh-and-blood coworkers are expected to be able to teach them.

More for You: Ease of Use Helps Robot Popularity

“The bottom line is that robots are not static anymore—they can be taught, and they can be improved,” said Shivam Vats, a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University's Robotics Institute and lead researcher of the paper Synergistic Scheduling of Learning and Allocation of Tasks in Human-Robot Team presented at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation in May. “But teaching a robot is expensive and laborious. How should the humans be spending their time? Should they be teaching the robot or doing the work?”

The conundrum is known to any parent of young children: Should you try to teach them to tie their shoes when they’re in pre-k, or just do it for them so you can get out the door?

For any job where a teachable robot is involved, there are three options that Vats considered: A robot does it, a human does it, or a human teaches the robot to do it. A future where robots teach humans was not considered. To determine which option is best, the algorithm essentially looks at descriptions of tasks and determines how hard it would be to teach a robot a new one.

Take Our Quiz: Historical Milestones for Industrial Robots

“The cost of a robot doing a task is low, but if it fails while doing it, it incurs a very high penalty,” said Vats. “So we only want to ask the robot to do it if it is confident of doing it correctly.”

That confidence—and the cost of teaching—are determined by comparing the descriptions of two tasks. A function tells whether the descriptions are similar or wildly different. If a job is too new for a machine, it’s better that a human does it. As of now, Vats’ method does not look at what kind of jobs are best suited to humans.

To put the algorithm to the test, Vats ran two experiments where a robot might have to learn a new task. In one, the task was to put a peg in a hole in a board. In another, there were Lego blocks that needed to be stacked according to shape and size. The algorithm proved effective in figuring out which new jobs to give the bots.

The project was a proof of concept, albeit one that could find use immediately in manufacturing. But there’s plenty more work that could be done.

Reader’s Choice: Robot Performs Laparoscopic Surgery

“A key assumption in my paper is that when you are teaching a robot, it learns a skill, but only on one task,” said Vats. “But if it trained on multiple tasks, the skills would be better put to use.”

With such an algorithm at hand, humans may never again waste their time trying to teach a robot something it can’t do properly. And maybe someday it will tell us when it’s best to teach kids to tie their shoes.

Michael Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.

Now researchers out of Carnegie Melon have created an algorithm to help answer that. question

When robots are programmed to do a single a task and repeat it for months, or years, on end, that question isn’t so hard to answer. The robots simply do the repetitive job they were designed for—there’s nothing to figure out when a machine’s capabilities are fixed. But now robots can be taught to do new jobs on the fly and their flesh-and-blood coworkers are expected to be able to teach them.

More for You: Ease of Use Helps Robot Popularity

“The bottom line is that robots are not static anymore—they can be taught, and they can be improved,” said Shivam Vats, a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University's Robotics Institute and lead researcher of the paper Synergistic Scheduling of Learning and Allocation of Tasks in Human-Robot Team presented at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation in May. “But teaching a robot is expensive and laborious. How should the humans be spending their time? Should they be teaching the robot or doing the work?”

The conundrum is known to any parent of young children: Should you try to teach them to tie their shoes when they’re in pre-k, or just do it for them so you can get out the door?

For any job where a teachable robot is involved, there are three options that Vats considered: A robot does it, a human does it, or a human teaches the robot to do it. A future where robots teach humans was not considered. To determine which option is best, the algorithm essentially looks at descriptions of tasks and determines how hard it would be to teach a robot a new one.

Take Our Quiz: Historical Milestones for Industrial Robots

“The cost of a robot doing a task is low, but if it fails while doing it, it incurs a very high penalty,” said Vats. “So we only want to ask the robot to do it if it is confident of doing it correctly.”

That confidence—and the cost of teaching—are determined by comparing the descriptions of two tasks. A function tells whether the descriptions are similar or wildly different. If a job is too new for a machine, it’s better that a human does it. As of now, Vats’ method does not look at what kind of jobs are best suited to humans.

To put the algorithm to the test, Vats ran two experiments where a robot might have to learn a new task. In one, the task was to put a peg in a hole in a board. In another, there were Lego blocks that needed to be stacked according to shape and size. The algorithm proved effective in figuring out which new jobs to give the bots.

The project was a proof of concept, albeit one that could find use immediately in manufacturing. But there’s plenty more work that could be done.

Reader’s Choice: Robot Performs Laparoscopic Surgery

“A key assumption in my paper is that when you are teaching a robot, it learns a skill, but only on one task,” said Vats. “But if it trained on multiple tasks, the skills would be better put to use.”

With such an algorithm at hand, humans may never again waste their time trying to teach a robot something it can’t do properly. And maybe someday it will tell us when it’s best to teach kids to tie their shoes.

Michael Abrams is a science and technology writer in Westfield, N.J.