A Deep Dive into the Future of Sargassum Innovation

A Deep Dive into the Future of Sargassum Innovation

Using a complex biorefinery process that breaks down Sargassum seaweed into its constituent parts, a team of researchers led by Princeton University hopes to provide valuable resources.

A team of researchers led by Princeton University with funding from Schmidt Sciences has embarked on an ambitious project to transform Sargassum seaweed into valuable resources. By developing a biorefinery process, scientists aim to convert the algae into a range of products, from biofuels to biodegradable plastics.

The Sargassum seaweed, native to the region and once a vital part of the marine ecosystem, has proliferated due to factors like pollution, deforestation, rising temperatures, and even dust from the Sahara reaching the atmosphere. Worse yet, due to climate change, the Sargassum growing season keeps expanding.

“These factors have created the perfect storm in which these endemic species of macroalgae have grown out of control,” explained José Avalos, associate professor in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Princeton University and the principal investigator on the project.

As Avalos explained, these massive blooms, which are found in the ocean from Florida to Puerto Rico, to the Caribbean and across the Atlantic to Northwest Africa, are endangering ecosystems and have wreaked havoc on coastal communities, damaging tourism industries, and overwhelming local infrastructure.

“You expect beautiful white sand and turquoise water,” he said about the beaches affected. “Instead, you get this brown, rotting biomass that stinks of rotten eggs. So it’s really affecting tourism and overwhelming landfills. And many of these countries don’t necessarily have the ability to deal with this ongoing crisis.”

Loretta Roberson, associate scientist at The University of Chicago’s Marine Biological Laboratory and a key researcher on the project, is focused on efficient methods for harvesting and processing Sargassum. She was recently a part of a project with the Department of Energy that was similar, in which they processed tropical seaweeds in Puerto Rico using a specialized vessel called the Damisela. The vessel will be modified for the Sargassum, and they are looking at how best to capture it.

“The Sargassum floats at the surface, like seaweed with little air bladders,” Roberson explained. “They’re not attached to anything and it’s convenient for collecting. So we are envisioning what is essentially a butterfly net that could scoop it up.”

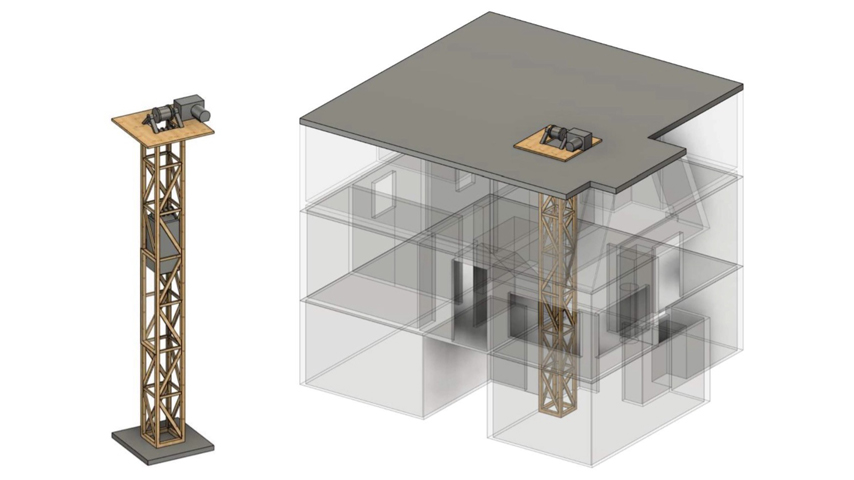

Once they’ve collected enough to work with, they begin the biorefinery process, a complex technological feat, involving breaking down the Sargassum into its constituent parts and then convert them into various products. “It’s like an oil refinery that produces several different products, but instead of crude oil, we’re using Sargassum,” Avalos said.

One key aspect of the project is the development of microorganisms that can efficiently break down the complex sugars in Sargassum. “This may involve engineering microorganisms or discovering them right from the Sargassum itself, that can naturally eat these sugars, metabolize them, and then convert them into valuable products like biofuels, chemicals, and even biodegradable plastics,” Avalos said.

Depending on the results, they may even be able to produce more valuable natural products like pigments, vitamins, and drugs. But right now, it’s all about identifying the best products to go after, and they have cast a wide net to do so.

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

Another area of opportunity is understanding the metal content of the Sargassum. It’s been found in some locations to have high concentrations of heavy metals including arsenic, which can make it toxic to people, but also valuable metals, such as rare-earth metals, used in computers, electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels.

So they will also be characterizing the biomass to understand what types of metals are present and exploring methods of how to remove the toxic ones to produce safe fertilizers or biostimulants and recover the valuable ones as an additional revenue stream.

But there are challenges. One area of concern for Roberson is protecting any potential marine life that relies on the Sargassum. “We’re developing techniques to avoid the collection of Sargassum that contains sensitive species,” she said. “That may involve working with underwater robotics that can help us locate fish and other organisms.”

Another significant challenge will be the variability of Sargassum biomass. The quantity and quality of Sargassum can fluctuate significantly depending on environmental factors like ocean currents, nutrient availability, and climate conditions. This variability can impact the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the biorefinery process.

Another significant challenge will be the variability of Sargassum biomass. The quantity and quality of Sargassum can fluctuate significantly depending on environmental factors like ocean currents, nutrient availability, and climate conditions. This variability can impact the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the biorefinery process.

Additionally, there are economic challenges associated with scaling up the biorefinery process. Developing the infrastructure, securing funding, and establishing markets for the produced goods will require significant investments and careful planning.

Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of this project are significant. By transforming a crisis into a resource, as Avalos noted, “The fundamental discoveries we will make, and technologies derived from them will have the potential to create new economic opportunities for people that have been negatively impacted by climate change.”

Cassandra Kelly is a technology writer in Columbus, Ohio.

The Sargassum seaweed, native to the region and once a vital part of the marine ecosystem, has proliferated due to factors like pollution, deforestation, rising temperatures, and even dust from the Sahara reaching the atmosphere. Worse yet, due to climate change, the Sargassum growing season keeps expanding.

Sargassum blooms

“These factors have created the perfect storm in which these endemic species of macroalgae have grown out of control,” explained José Avalos, associate professor in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Princeton University and the principal investigator on the project. As Avalos explained, these massive blooms, which are found in the ocean from Florida to Puerto Rico, to the Caribbean and across the Atlantic to Northwest Africa, are endangering ecosystems and have wreaked havoc on coastal communities, damaging tourism industries, and overwhelming local infrastructure.

“You expect beautiful white sand and turquoise water,” he said about the beaches affected. “Instead, you get this brown, rotting biomass that stinks of rotten eggs. So it’s really affecting tourism and overwhelming landfills. And many of these countries don’t necessarily have the ability to deal with this ongoing crisis.”

Loretta Roberson, associate scientist at The University of Chicago’s Marine Biological Laboratory and a key researcher on the project, is focused on efficient methods for harvesting and processing Sargassum. She was recently a part of a project with the Department of Energy that was similar, in which they processed tropical seaweeds in Puerto Rico using a specialized vessel called the Damisela. The vessel will be modified for the Sargassum, and they are looking at how best to capture it.

“The Sargassum floats at the surface, like seaweed with little air bladders,” Roberson explained. “They’re not attached to anything and it’s convenient for collecting. So we are envisioning what is essentially a butterfly net that could scoop it up.”

Once they’ve collected enough to work with, they begin the biorefinery process, a complex technological feat, involving breaking down the Sargassum into its constituent parts and then convert them into various products. “It’s like an oil refinery that produces several different products, but instead of crude oil, we’re using Sargassum,” Avalos said.

Engineering microorganisms

One key aspect of the project is the development of microorganisms that can efficiently break down the complex sugars in Sargassum. “This may involve engineering microorganisms or discovering them right from the Sargassum itself, that can naturally eat these sugars, metabolize them, and then convert them into valuable products like biofuels, chemicals, and even biodegradable plastics,” Avalos said.Depending on the results, they may even be able to produce more valuable natural products like pigments, vitamins, and drugs. But right now, it’s all about identifying the best products to go after, and they have cast a wide net to do so.

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

Another area of opportunity is understanding the metal content of the Sargassum. It’s been found in some locations to have high concentrations of heavy metals including arsenic, which can make it toxic to people, but also valuable metals, such as rare-earth metals, used in computers, electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels.

So they will also be characterizing the biomass to understand what types of metals are present and exploring methods of how to remove the toxic ones to produce safe fertilizers or biostimulants and recover the valuable ones as an additional revenue stream.

Vulnerable species

But there are challenges. One area of concern for Roberson is protecting any potential marine life that relies on the Sargassum. “We’re developing techniques to avoid the collection of Sargassum that contains sensitive species,” she said. “That may involve working with underwater robotics that can help us locate fish and other organisms.”

High-Impact Engineering

Mechanical Engineering magazine is available for ASME members. Read the magazine wherever you go!

Additionally, there are economic challenges associated with scaling up the biorefinery process. Developing the infrastructure, securing funding, and establishing markets for the produced goods will require significant investments and careful planning.

Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of this project are significant. By transforming a crisis into a resource, as Avalos noted, “The fundamental discoveries we will make, and technologies derived from them will have the potential to create new economic opportunities for people that have been negatively impacted by climate change.”

Cassandra Kelly is a technology writer in Columbus, Ohio.