Do Gravity Batteries Scale to Household Size?

Do Gravity Batteries Scale to Household Size?

Some entrepreneurs believe lifting and lowering large weights may be an efficient energy storage system. A team of Purdue engineering students tested the concept for home use.

There comes a time in every engineer’s career when all options have been exhausted, and the project must end. Sometimes things just don’t work out, but it’s about the lessons learned along the way that make it worth it.

Caden Jarausch, a senior in mechanical engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., realized this rather early in his budding career, and he took those lessons and published a paper outlining all of his research and discovery despite not having a solution at the end.

“Sometimes you don’t get your desired outcome,” he said. “But if I could save someone else weeks or even months of coming to the same conclusion that I did, then that makes it all worth it.”

Jarausch’s work centered around the idea that gravity batteries could be made small enough to serve a single-family home, allowing it to run off stored energy. Gravity batteries work by leveraging the fundamental principle of potential energy. Essentially, they store energy by elevating a mass against the force of gravity—typically a large weight, concrete block, or even by pumping water up a hill.

This stored potential energy is then recovered by allowing the mass to descend. The controlled descent of the weight drives a generator which then converts the potential energy back into the system. This technology is currently being explored in various large-scale solar, wind, and hydroelectric operations, but it has not been widely studied for small-scale projects.

At Purdue, the DC Nanogrid House is a student home that has been fully retrofitted with a DC-powered nanogrid to serve as a testbed for all kinds of research. The students wanted to find a way to replace lithium-ion batteries in the home because they are not terribly efficient at storing energy from the home’s solar power system. In fact, if left partially charged, the maximum capacity of lithium-ion batteries can drop between 10 to 15 percent in a single year. The batteries also still produce emissions. For every one kilowatt-hour of storage capacity, roughly 74 grams of carbon dioxide is emitted.

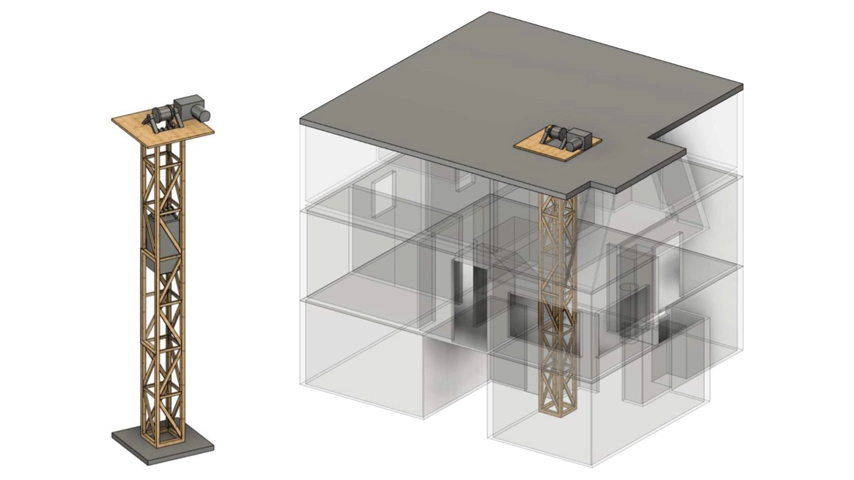

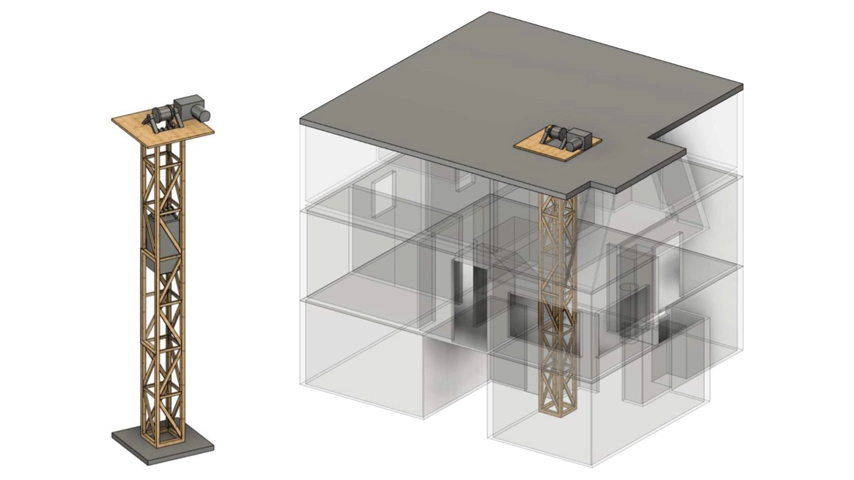

This problem made the DC Nanogrid House the perfect place for Jarausch to test out multiple approaches with the gravity battery. They had an old ventilation shaft in the house to work with, which stretched all four floors of the house. To support the weight connected to the motor, they needed to design a heavy-duty structure inside the shaft, similar to that of a modern elevator, utilizing a motor-pulley system.

Guide rollers were attached to the concrete weight allowing it to ride on carbon steel guide rails within the shaft. Polyurethane buffers were also placed on the bottom of the shaft to help slow the descent of the weight at the bottom of the shaft. Lastly, an overspeed governor was selected as the primary safety mechanism, with the ability to immediately stop the freefall of the weight in case of emergency.

Even with a 2,078-kilogram weight, they ultimately found that the cost of the materials used to build the prototype did not make sense for how little energy the battery was able to store.

“We found that the energy storage capacity diminishes significantly with decreasing size,” Jarausch said. “The weight of the moving mass, a crucial factor, scales cubically, making it impractical for individual homes. This technology is more suitable for larger-scale applications like powering a city block or a small community."

This conclusion was difficult for Jarausch. But he knew his process and calculations were sound and that even if it wasn’t the answer he was hoping for, his research could still be valuable to the engineering community. So he published the paper through Purdue and was invited to present his findings at the 2024 Herrick Conferences in Indiana.

“I was one of the youngest people there and I listened to these presentations that were all super complex, revolutionary, and every single one of them seemed like they had some promise to them,” he said. “I felt a little disappointed. My whole presentation was about the application of a technology that wasn't viable. But I got a lot of people who came up to me after and said I did a great job.”

“I was one of the youngest people there and I listened to these presentations that were all super complex, revolutionary, and every single one of them seemed like they had some promise to them,” he said. “I felt a little disappointed. My whole presentation was about the application of a technology that wasn't viable. But I got a lot of people who came up to me after and said I did a great job.”

More Batteries: A Solid Foundation for Battery Technology

Jarausch said that many of the engineers at the conference had never heard about gravity batteries, and one person told him that he may have helped him find an entirely new approach to his own research project.

“That’s when it really clicked for me,” Jarausch said. “It’s okay if your research doesn’t go the way that you want. You should still put it out there if you think that the result’s important and if you think that’ll save people time or give people important information.”

The prototype still remains in the DC Nanogrid House at Purdue and can be tested and understood by the students. Now, Jarausch is focusing on graduation and will be equipped for any challenge he may take on.

Cassandra Kelly is a technology writer in Columbus, Ohio.

Caden Jarausch, a senior in mechanical engineering at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., realized this rather early in his budding career, and he took those lessons and published a paper outlining all of his research and discovery despite not having a solution at the end.

“Sometimes you don’t get your desired outcome,” he said. “But if I could save someone else weeks or even months of coming to the same conclusion that I did, then that makes it all worth it.”

Jarausch’s work centered around the idea that gravity batteries could be made small enough to serve a single-family home, allowing it to run off stored energy. Gravity batteries work by leveraging the fundamental principle of potential energy. Essentially, they store energy by elevating a mass against the force of gravity—typically a large weight, concrete block, or even by pumping water up a hill.

This stored potential energy is then recovered by allowing the mass to descend. The controlled descent of the weight drives a generator which then converts the potential energy back into the system. This technology is currently being explored in various large-scale solar, wind, and hydroelectric operations, but it has not been widely studied for small-scale projects.

At Purdue, the DC Nanogrid House is a student home that has been fully retrofitted with a DC-powered nanogrid to serve as a testbed for all kinds of research. The students wanted to find a way to replace lithium-ion batteries in the home because they are not terribly efficient at storing energy from the home’s solar power system. In fact, if left partially charged, the maximum capacity of lithium-ion batteries can drop between 10 to 15 percent in a single year. The batteries also still produce emissions. For every one kilowatt-hour of storage capacity, roughly 74 grams of carbon dioxide is emitted.

This problem made the DC Nanogrid House the perfect place for Jarausch to test out multiple approaches with the gravity battery. They had an old ventilation shaft in the house to work with, which stretched all four floors of the house. To support the weight connected to the motor, they needed to design a heavy-duty structure inside the shaft, similar to that of a modern elevator, utilizing a motor-pulley system.

Guide rollers were attached to the concrete weight allowing it to ride on carbon steel guide rails within the shaft. Polyurethane buffers were also placed on the bottom of the shaft to help slow the descent of the weight at the bottom of the shaft. Lastly, an overspeed governor was selected as the primary safety mechanism, with the ability to immediately stop the freefall of the weight in case of emergency.

Even with a 2,078-kilogram weight, they ultimately found that the cost of the materials used to build the prototype did not make sense for how little energy the battery was able to store.

“We found that the energy storage capacity diminishes significantly with decreasing size,” Jarausch said. “The weight of the moving mass, a crucial factor, scales cubically, making it impractical for individual homes. This technology is more suitable for larger-scale applications like powering a city block or a small community."

This conclusion was difficult for Jarausch. But he knew his process and calculations were sound and that even if it wasn’t the answer he was hoping for, his research could still be valuable to the engineering community. So he published the paper through Purdue and was invited to present his findings at the 2024 Herrick Conferences in Indiana.

The March Issue Is Ready

Mechanical Engineering magazine is available for ASME members. Read the magazine wherever you go!

More Batteries: A Solid Foundation for Battery Technology

Jarausch said that many of the engineers at the conference had never heard about gravity batteries, and one person told him that he may have helped him find an entirely new approach to his own research project.

“That’s when it really clicked for me,” Jarausch said. “It’s okay if your research doesn’t go the way that you want. You should still put it out there if you think that the result’s important and if you think that’ll save people time or give people important information.”

The prototype still remains in the DC Nanogrid House at Purdue and can be tested and understood by the students. Now, Jarausch is focusing on graduation and will be equipped for any challenge he may take on.

Cassandra Kelly is a technology writer in Columbus, Ohio.