8 Ways 3D Printers Build Bigger

8 Ways 3D Printers Build Bigger

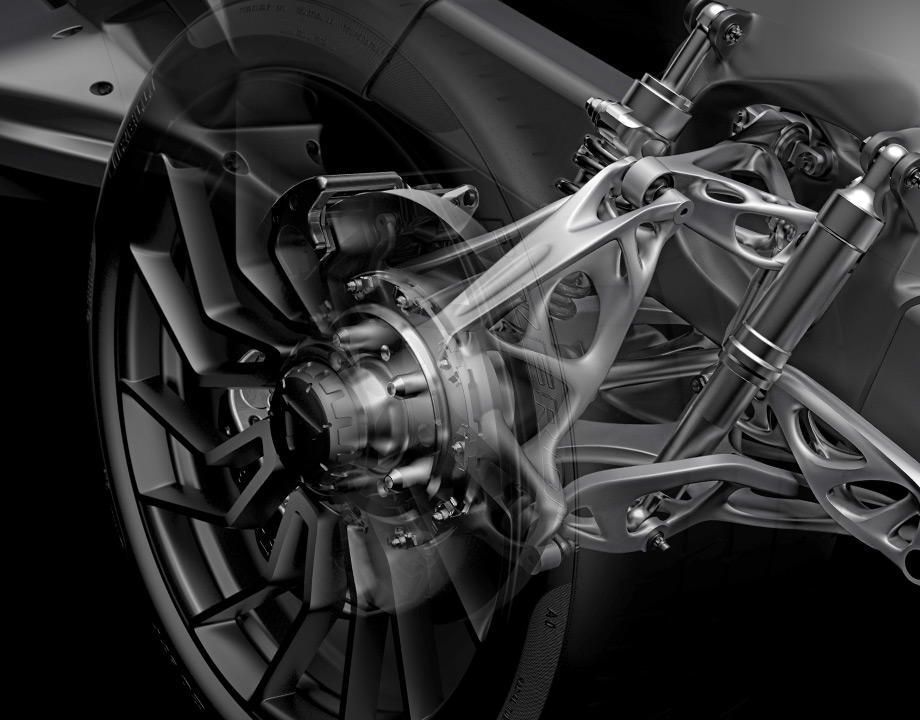

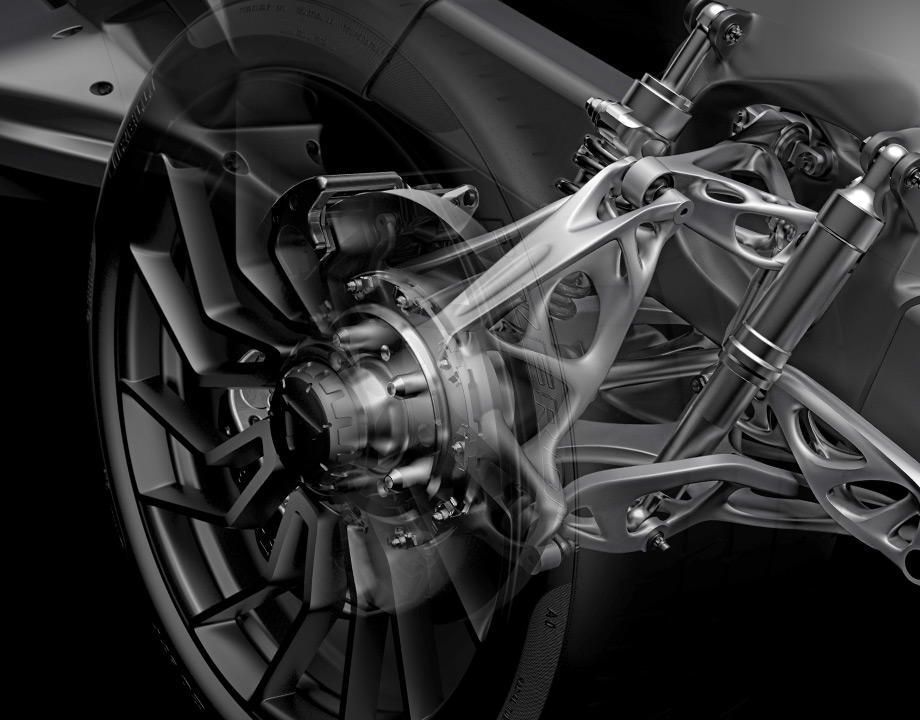

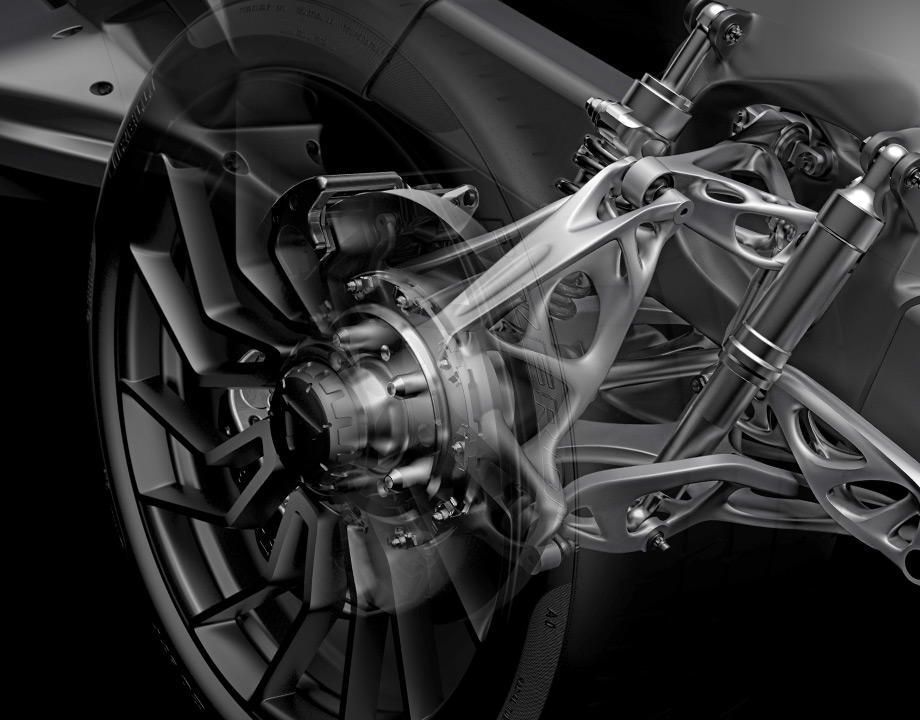

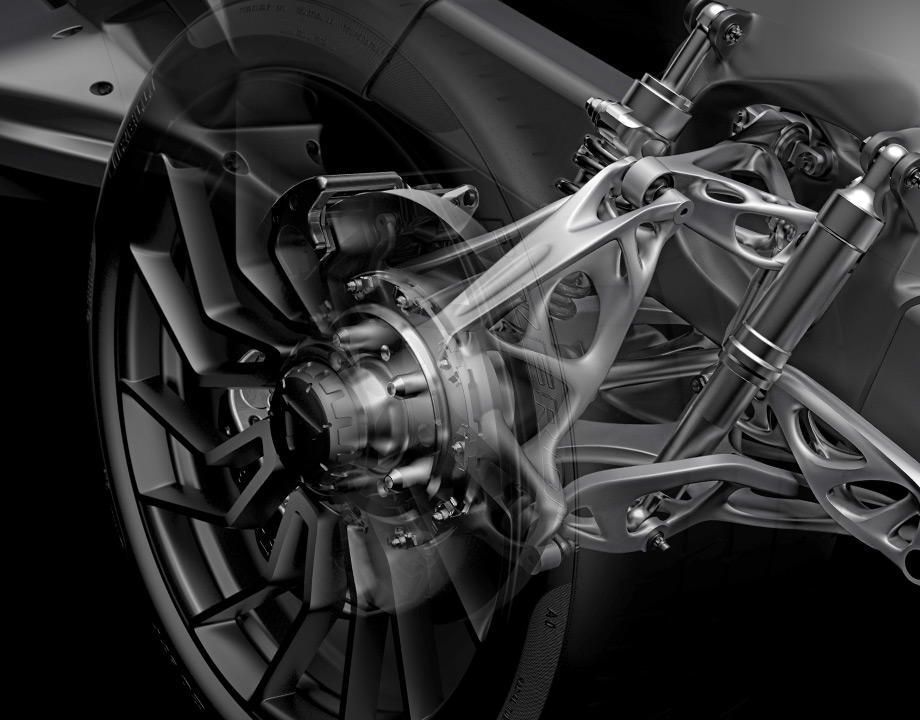

The 3D-printed chassis of Divergent’s Blade supercar weighs just over 100 pounds, enabling it to go from 0 to 60 mph in just 2 seconds. Image: Divergent Technologies

Not too long ago, additive manufacturers measured their workspace in centimeters. Today, they are printing rockets, boats, motor vehicles, small bridges, and a bunch of other products. While some of these objects are simply demonstrations to show what 3D printing can do, others are commercial products that use additive to slash time and costs.

Relativity Space’s goal is to slash the cost of launching a payload into space to $10 million from $100 million today. To accomplish that goal, it is using 3D printing to reduce part counts by 99 percent, increase production times by a factor of 10, and make it possible to rapidly incorporate new advances into its rockets and engines.

Relativity’s Aeon 1 liquid methane and liquid oxygen-powered rocket engine produces 15,500 pounds of thrust. It has only about 100 nickel parts and has undergone more than 200 test firings. Its Terran 1 launch vehicle will use nine Aeon engines in the first stage and one in the second stage.

The company produces the rocket and engine with its own Stargate printer, which has two robotic arms for selective laser sintering. The company expects to 3D-print at least 95 percent of its launcher by the end of 2020, and build a complete launch vehicle from scratch within 60 days.

Over the past couple of years, 3D-printed buildings have become a thing. In 2018, ICON became the first U.S. company to secure a building permit for a 3D printed home and built a small proof of concept in Austin, Texas. It is now teaming up with Mobile Loaves & Fishes to print small homes for the homeless and with New Story to build similarly sized units in Latin America.

The company uses a proprietary Portland cement formulation, and its new Vulcan II printer can print single-story buildings up to 2,000 square feet.

ICON is not the only game in town. In China, HuaShang Tengda printed a two-story, 4550-square-foot villa from 20 tons of concrete in just 45 days. To improve productivity, the company framed the house, including rebar supports, plumbing, and electrical wire, then printed over the frame.

Recommended for You: New 3D Printer Extruder Takes Manufacturing to Next Level

Sunconomy and Forge New teamed together to print two-story homes that contain rebar supports. Meanwhile, Apis Cor recently completed a two-story, 7,000-square-foot administrative building in Dubai that is the largest 3D printed building to date.

Printing in concrete costs significantly less than conventional building due to lower material and labor costs. Some buildings are solid enough to stand up to an 8.0 earthquake.

One problem with campers is that their metal skins and frames are prone to water damage. Randy Janes, who spent a decade in the RV business, decided to address this by 3D printing an RV.

Working with CreateCafe, a 3D printing business in Saskatchewan, Canada, and Saskatchewan Polytechnic’s mechanical engineers, he printed an airtight RV from PETG (polyethylene terephthalate glycol) polymer. The 13 by 6 feet camper weighed 600 pounds and took 230 hours to 3D print. When completed, it was the largest indoor 3D-print ever done.

Named “The Wave,” it not only stands up to corrosion but has an estimated lifespan of 100 years. It also has a particularly Canadian convenience: Three covered holes in the floor that users can remove to go ice fishing on a frozen lake. Janes’ company, Wave of the Future, plans to commercialize the trailer in 2020, along with a 16-foot, 19-foot, and a truck-bed camper models.

The University of Maine launched the 3Dirigo, the world’s first 3D printed boat in October 2019.

The 25-feet-long boat weighs 2.2 tons but took only 70 hours to print. The reason: A gantry style 3D printer that measures 100 by 22 by 10 feet from Ingersoll Machine Tools that reaches deposition speeds of up to 500 pounds per hour.

The machine was installed under a partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory that specializes in large 3D structures. It also uses an unusual material that is based on a combination of renewable wood cellulose (easily sourced in Maine) and resin.

The Guinness Book of Records has officially recognized it as the world’s largest 3D printed object. Meanwhile, the school is looking at building a 75-feet-long mold for a girder for a bridge that will be built in Hampden, Maine, in summer 2020.

To build a 777X aircraft wing, Boeing needed a really big tool to secure the carbon composite wing skin for trimming and align holes for drilling.

In 2016, Oak Ridge National Laboratory built them one. It measured 17.5 by 5.5 by 1.5 feet and weighed 1650 pounds. That was large enough for The Guinness Book of World Records to certify it as the world’s largest solid 3D-printed object.

You May Also Like: 3D Printing Houses for Utopia

Boeing made it from carbon-reinforced ABS thermoplastic on a customized fused filament fabrication (FFM) 3D printer. Surprisingly, it took only 30 hours to print, whereas in comparison, it would take three months to manufacture a conventional tool from metal.

Verification tests showed the composite tool worked just as well as the metal version, but saved time, labor and production cost, and energy.

A lot has changed since 2014, when Local Motors, Oak Ridge National Lab, and Cincinnati Inc. collaborated on the Strati, the first car with a 3D printed shell. Local Motors is now producing the Olli 2.0, an eight passenger, level 4 autonomous shuttle.

The minibus is 80 percent 3D printed, with a carbon-reinforced monocoque type body that supports structural loads and eliminates the need for a traditional frame. The car is undergoing testing on several college campuses and cities around the world. Local Motors says 3D printing slashes tooling costs by 50 percent and production time by 90 percent.

It is not the only car company leveraging additive manufacturing. Divergent 3D’s Blade supercar uses selective metal melting for its 102 pound chassis that is made from printed aluminum joints connected to carbon fiber tubes. The result is a vehicle that goes from 0 to 60 miles per hour in just 2 seconds.

At the other end of the spectrum, China’s Polymaker has teamed with Italian design studio XEV to create an FFF printed electric car that can reach 43 miles per hour and travel for 90 miles. The 1000 pounds auto will sell for just $7,500.

With all its canals, The Netherlands is a natural leader in 3D-printed bridges. The first one, designed by Eindhoven University of Technology , was printed with pre-stressed concrete reinforced with steel wires while printing. The researchers built multiple parts, which they then assembled in three months in Gemert.

The latest example comes from China, where Professor Xu Weiguo of Shanghai’s Tsinghua University built a 26-meter-long polyethylene-concrete bridge from 44 hollow 3D units plus an additional 68 handrail units using robotic arms.

In both cases, the researchers found that the 3D process was faster and used less material than conventional concrete bridges. Both research teams would eventually like to build bridges from a single, large print.

A Dutch firm, MX3D, has already done that. Using robots, it printed a 12 by 6 meters steel bridge that will be installed along one of the canals in Amsterdam next year. The company says it could have built the bridge in place, but the city thought it would be too dangerous.

In November 2017, Bureau Veritas certified the WAAMpeller, the first 3D-printed ship propeller. Made from 298 layers of nickel aluminum bronze alloy by wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM), the propeller measured 4.4 feet in diameter and weighed nearly 900 pounds.

After printing, RAMLAB (Rotterdam Additive Manufacturing LAB) CNC-milled it to a final finish. Despite the object’s size, the real challenge was the design: The WAAMpeller has a double-curved geometric shape that included overhanging sections that present printing challenges.

Editors' Pick: Navy Sails Into Supply Chain with Metal 3D Printing

Bureau Veritas verified the entire process, from development through production and testing process. Damen Shipyard, another partner in development, then mounted the propeller on a 17-meter Stan Tug harbor tugboat.

In tests, it showed the same performance as a conventional cast propeller, including pulling strength and full throttle ahead to full throttle reverse (the heaviest loading a propeller experiences). The goal again is faster and lower cost production.

Alan S. Brown is senior editor.

Rockets

Relativity Space’s goal is to slash the cost of launching a payload into space to $10 million from $100 million today. To accomplish that goal, it is using 3D printing to reduce part counts by 99 percent, increase production times by a factor of 10, and make it possible to rapidly incorporate new advances into its rockets and engines.

Relativity’s Aeon 1 liquid methane and liquid oxygen-powered rocket engine produces 15,500 pounds of thrust. It has only about 100 nickel parts and has undergone more than 200 test firings. Its Terran 1 launch vehicle will use nine Aeon engines in the first stage and one in the second stage.

The company produces the rocket and engine with its own Stargate printer, which has two robotic arms for selective laser sintering. The company expects to 3D-print at least 95 percent of its launcher by the end of 2020, and build a complete launch vehicle from scratch within 60 days.

Buildings

Over the past couple of years, 3D-printed buildings have become a thing. In 2018, ICON became the first U.S. company to secure a building permit for a 3D printed home and built a small proof of concept in Austin, Texas. It is now teaming up with Mobile Loaves & Fishes to print small homes for the homeless and with New Story to build similarly sized units in Latin America.

The company uses a proprietary Portland cement formulation, and its new Vulcan II printer can print single-story buildings up to 2,000 square feet.

ICON is not the only game in town. In China, HuaShang Tengda printed a two-story, 4550-square-foot villa from 20 tons of concrete in just 45 days. To improve productivity, the company framed the house, including rebar supports, plumbing, and electrical wire, then printed over the frame.

Recommended for You: New 3D Printer Extruder Takes Manufacturing to Next Level

Sunconomy and Forge New teamed together to print two-story homes that contain rebar supports. Meanwhile, Apis Cor recently completed a two-story, 7,000-square-foot administrative building in Dubai that is the largest 3D printed building to date.

Printing in concrete costs significantly less than conventional building due to lower material and labor costs. Some buildings are solid enough to stand up to an 8.0 earthquake.

Recreational Vehicles

One problem with campers is that their metal skins and frames are prone to water damage. Randy Janes, who spent a decade in the RV business, decided to address this by 3D printing an RV.

Working with CreateCafe, a 3D printing business in Saskatchewan, Canada, and Saskatchewan Polytechnic’s mechanical engineers, he printed an airtight RV from PETG (polyethylene terephthalate glycol) polymer. The 13 by 6 feet camper weighed 600 pounds and took 230 hours to 3D print. When completed, it was the largest indoor 3D-print ever done.

Named “The Wave,” it not only stands up to corrosion but has an estimated lifespan of 100 years. It also has a particularly Canadian convenience: Three covered holes in the floor that users can remove to go ice fishing on a frozen lake. Janes’ company, Wave of the Future, plans to commercialize the trailer in 2020, along with a 16-foot, 19-foot, and a truck-bed camper models.

Boats

The University of Maine launched the 3Dirigo, the world’s first 3D printed boat in October 2019.

The 25-feet-long boat weighs 2.2 tons but took only 70 hours to print. The reason: A gantry style 3D printer that measures 100 by 22 by 10 feet from Ingersoll Machine Tools that reaches deposition speeds of up to 500 pounds per hour.

The machine was installed under a partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory that specializes in large 3D structures. It also uses an unusual material that is based on a combination of renewable wood cellulose (easily sourced in Maine) and resin.

The Guinness Book of Records has officially recognized it as the world’s largest 3D printed object. Meanwhile, the school is looking at building a 75-feet-long mold for a girder for a bridge that will be built in Hampden, Maine, in summer 2020.

Giant Tools

To build a 777X aircraft wing, Boeing needed a really big tool to secure the carbon composite wing skin for trimming and align holes for drilling.

In 2016, Oak Ridge National Laboratory built them one. It measured 17.5 by 5.5 by 1.5 feet and weighed 1650 pounds. That was large enough for The Guinness Book of World Records to certify it as the world’s largest solid 3D-printed object.

You May Also Like: 3D Printing Houses for Utopia

Boeing made it from carbon-reinforced ABS thermoplastic on a customized fused filament fabrication (FFM) 3D printer. Surprisingly, it took only 30 hours to print, whereas in comparison, it would take three months to manufacture a conventional tool from metal.

Verification tests showed the composite tool worked just as well as the metal version, but saved time, labor and production cost, and energy.

Vehicles

A lot has changed since 2014, when Local Motors, Oak Ridge National Lab, and Cincinnati Inc. collaborated on the Strati, the first car with a 3D printed shell. Local Motors is now producing the Olli 2.0, an eight passenger, level 4 autonomous shuttle.

The minibus is 80 percent 3D printed, with a carbon-reinforced monocoque type body that supports structural loads and eliminates the need for a traditional frame. The car is undergoing testing on several college campuses and cities around the world. Local Motors says 3D printing slashes tooling costs by 50 percent and production time by 90 percent.

It is not the only car company leveraging additive manufacturing. Divergent 3D’s Blade supercar uses selective metal melting for its 102 pound chassis that is made from printed aluminum joints connected to carbon fiber tubes. The result is a vehicle that goes from 0 to 60 miles per hour in just 2 seconds.

At the other end of the spectrum, China’s Polymaker has teamed with Italian design studio XEV to create an FFF printed electric car that can reach 43 miles per hour and travel for 90 miles. The 1000 pounds auto will sell for just $7,500.

Bridges

With all its canals, The Netherlands is a natural leader in 3D-printed bridges. The first one, designed by Eindhoven University of Technology , was printed with pre-stressed concrete reinforced with steel wires while printing. The researchers built multiple parts, which they then assembled in three months in Gemert.

The latest example comes from China, where Professor Xu Weiguo of Shanghai’s Tsinghua University built a 26-meter-long polyethylene-concrete bridge from 44 hollow 3D units plus an additional 68 handrail units using robotic arms.

In both cases, the researchers found that the 3D process was faster and used less material than conventional concrete bridges. Both research teams would eventually like to build bridges from a single, large print.

A Dutch firm, MX3D, has already done that. Using robots, it printed a 12 by 6 meters steel bridge that will be installed along one of the canals in Amsterdam next year. The company says it could have built the bridge in place, but the city thought it would be too dangerous.

Ship Propellers

In November 2017, Bureau Veritas certified the WAAMpeller, the first 3D-printed ship propeller. Made from 298 layers of nickel aluminum bronze alloy by wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM), the propeller measured 4.4 feet in diameter and weighed nearly 900 pounds.

After printing, RAMLAB (Rotterdam Additive Manufacturing LAB) CNC-milled it to a final finish. Despite the object’s size, the real challenge was the design: The WAAMpeller has a double-curved geometric shape that included overhanging sections that present printing challenges.

Editors' Pick: Navy Sails Into Supply Chain with Metal 3D Printing

Bureau Veritas verified the entire process, from development through production and testing process. Damen Shipyard, another partner in development, then mounted the propeller on a 17-meter Stan Tug harbor tugboat.

In tests, it showed the same performance as a conventional cast propeller, including pulling strength and full throttle ahead to full throttle reverse (the heaviest loading a propeller experiences). The goal again is faster and lower cost production.

Alan S. Brown is senior editor.