California Looks to Develop Its Lithium Valley

California Looks to Develop Its Lithium Valley

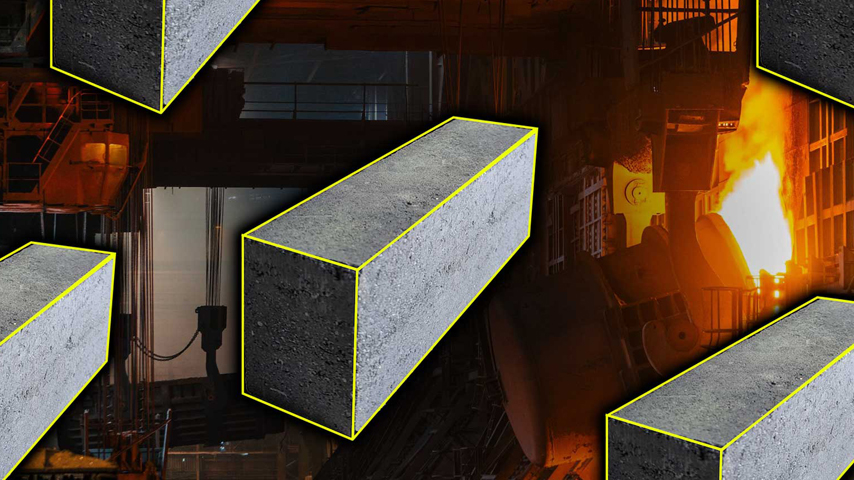

A recent report recommends upgrading geothermal plants, like the one in the image, to extract the metal, crucial for EV batteries. Some companies are already moving in that direction.

Money makes the world go ‘round, but lithium is the metallic element that helps spin the wheels of electric vehicles. The lithium-ion battery is a crucial component of most rechargeable technologies, whether EVs, laptop computers, or energy storage for solar power, and recent demand has led to a supply crunch.

While virtually all the lithium used in the United States is imported from South America, lithium itself is not necessarily rare. In fact, one of the richest lithium resources in the world is in California and is relatively easy to access by an industry already active in the state.

That’s the finding of a state-sponsored blue-ribbon panel, convened in 2021, which released its final report in early December 2022. The commission looked at the potential for extracting lithium from the hot brines brought up from deep wells near the Salton Sea, a region of southern California that is a geothermal hotspot. Facilities there have been using the brine to generate electricity for years, but only in the past few years has the mineral content of the brine received scrutiny.

“The National Renewable Energy Laboratory reported in 2021 that the Salton Sea Known Geothermal Area has the capacity to produce 600,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate equivalent products per year,” said Rod Colwell, Chief Executive Officer of Controlled Thermal Resources (CTR), a geothermal company based in El Centro, Calif. That’s the equivalent to current worldwide production.

The resource is so rich that boosters have rebranded the Imperial Valley, long known for its irrigated farmland, as the Lithium Valley. One of the key recommendations of the so-called Lithium Valley Commission was to “accelerate state planning for investment and upgrades in transmission for geothermal power plants in Imperial Valley to be online in 2024 and over the next decade.”

At present, lithium is mined either via hard rock or evaporating lithium-rich water, but both those methods can take an environmental toll. For instance, it may take many months for brines to evaporate, leaving thousands of square miles covered by a toxic solution.

What Do You Know About Geothermal Energy? Take Our Quiz

The commission instead explored the concept of what is called direct lithium extraction, which recovers lithium via a material that attracts the dissolved metal in the brine. Companies can add a DLE system to an existing geothermal plant or build one as an integral part of a new plant. According to Colwell, who was a member of the of the Lithium Valley Commission and whose company is developing a DLE facility, “There will be no process waste tailings going to landfills from our project. In fact, we intend to sell several additional products, including a material that will help make CO2-free cement. CTR’s location is also ideally suited to colocate cathode and battery manufacturing facilities, making the entire battery supply chain more sustainable.”

The development of a Lithium Valley battery industry is already happening. In January, EV battery startup Statevolt purchased a 135-acre site in the Imperial Valley to construct a factory expected to produce batteries for as many as 650,000 EVs per year. According to a press statement, the company had signed an agreement to purchase lithium for the batteries from CTR’s geothermal facility. By keeping the supply chain for battery production localized, the company hopes to reduce some of additional environmental impacts of manufacturing the batteries, such as transportation emissions.

“CTR’s process utilizes 100 percent renewable energy and steam and eliminates all overseas processing. The operations have a minimal physical footprint and a near-zero carbon footprint and will produce battery-grade lithium products in a matter of hours, compared to months, to produce products from evaporation extraction methods or open pit mining operations,” Colwell said. “Put simply; it’s cleaner, faster, and more efficient.”

Check Out the Infographic: Geothermal Energy is Heat Under Our Feet

The Lithium Valley Commission produced a list of 15 recommendations, many of which were meant to address questions of inequity and community disruption. In addition to R&D proposals, such as increased funding to develop battery component manufacturing and recycling, especially cathode production, the final report called for funding a health analysis, provide economic assistance, and promote science and technology education for people living in the region.

For Colwell, one of the biggest takeaways from the commission’s work wasn’t the scope of the opportunity, but the fact that the geothermal sector in the area had such a low profile. “Given that Imperial County has been producing clean geothermal power for over 40 years, I was surprised that there wasn’t more awareness of its sustainable attributes within the community,” he said. “I think we all had to go through a much deeper education process to understand what the community needed to know and how best to keep those communication lines open in the future.”

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.

While virtually all the lithium used in the United States is imported from South America, lithium itself is not necessarily rare. In fact, one of the richest lithium resources in the world is in California and is relatively easy to access by an industry already active in the state.

That’s the finding of a state-sponsored blue-ribbon panel, convened in 2021, which released its final report in early December 2022. The commission looked at the potential for extracting lithium from the hot brines brought up from deep wells near the Salton Sea, a region of southern California that is a geothermal hotspot. Facilities there have been using the brine to generate electricity for years, but only in the past few years has the mineral content of the brine received scrutiny.

“The National Renewable Energy Laboratory reported in 2021 that the Salton Sea Known Geothermal Area has the capacity to produce 600,000 metric tons of lithium carbonate equivalent products per year,” said Rod Colwell, Chief Executive Officer of Controlled Thermal Resources (CTR), a geothermal company based in El Centro, Calif. That’s the equivalent to current worldwide production.

The resource is so rich that boosters have rebranded the Imperial Valley, long known for its irrigated farmland, as the Lithium Valley. One of the key recommendations of the so-called Lithium Valley Commission was to “accelerate state planning for investment and upgrades in transmission for geothermal power plants in Imperial Valley to be online in 2024 and over the next decade.”

At present, lithium is mined either via hard rock or evaporating lithium-rich water, but both those methods can take an environmental toll. For instance, it may take many months for brines to evaporate, leaving thousands of square miles covered by a toxic solution.

What Do You Know About Geothermal Energy? Take Our Quiz

The commission instead explored the concept of what is called direct lithium extraction, which recovers lithium via a material that attracts the dissolved metal in the brine. Companies can add a DLE system to an existing geothermal plant or build one as an integral part of a new plant. According to Colwell, who was a member of the of the Lithium Valley Commission and whose company is developing a DLE facility, “There will be no process waste tailings going to landfills from our project. In fact, we intend to sell several additional products, including a material that will help make CO2-free cement. CTR’s location is also ideally suited to colocate cathode and battery manufacturing facilities, making the entire battery supply chain more sustainable.”

The development of a Lithium Valley battery industry is already happening. In January, EV battery startup Statevolt purchased a 135-acre site in the Imperial Valley to construct a factory expected to produce batteries for as many as 650,000 EVs per year. According to a press statement, the company had signed an agreement to purchase lithium for the batteries from CTR’s geothermal facility. By keeping the supply chain for battery production localized, the company hopes to reduce some of additional environmental impacts of manufacturing the batteries, such as transportation emissions.

“CTR’s process utilizes 100 percent renewable energy and steam and eliminates all overseas processing. The operations have a minimal physical footprint and a near-zero carbon footprint and will produce battery-grade lithium products in a matter of hours, compared to months, to produce products from evaporation extraction methods or open pit mining operations,” Colwell said. “Put simply; it’s cleaner, faster, and more efficient.”

Check Out the Infographic: Geothermal Energy is Heat Under Our Feet

The Lithium Valley Commission produced a list of 15 recommendations, many of which were meant to address questions of inequity and community disruption. In addition to R&D proposals, such as increased funding to develop battery component manufacturing and recycling, especially cathode production, the final report called for funding a health analysis, provide economic assistance, and promote science and technology education for people living in the region.

For Colwell, one of the biggest takeaways from the commission’s work wasn’t the scope of the opportunity, but the fact that the geothermal sector in the area had such a low profile. “Given that Imperial County has been producing clean geothermal power for over 40 years, I was surprised that there wasn’t more awareness of its sustainable attributes within the community,” he said. “I think we all had to go through a much deeper education process to understand what the community needed to know and how best to keep those communication lines open in the future.”

Jeffrey Winters is editor in chief of Mechanical Engineering magazine.