Drone on the Farm

Drone on the Farm

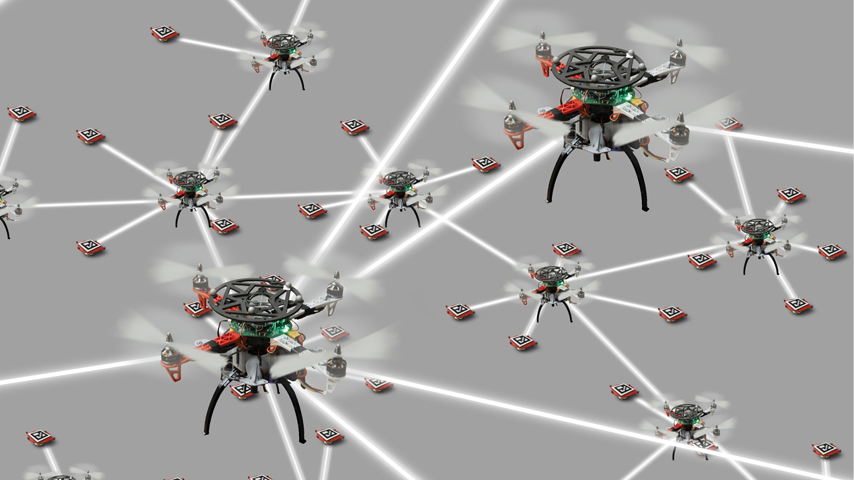

Drones will attract each other much like bee swarms that move to the best pollinator locations in groups.

In the future, swarms of drones will fly among farm fields, mapping the location of weeds with the help of their onboard vision. These little drones, each about the size of a bee, will help farmers improve crop yields with less herbicide. And they’ll be available to farmers at a low cost.

A group of Italian researchers at the Italian National Research Council is now developing the drones as part of a project called Swarm Robotics for Agricultural Applications, or SAGA.

The drones are actually kitted out with robotic controls that let them fly, map, and stay in touch. This type of robotics, swarm robotics, consists of teams of very small robots built to best suit the environment they move within.

Each individual drone weighs around three pounds and flies for 20 to 30 minutes. They generally fly in packs of 20 to 30, says Vito Trianni, who heads the project. He’s part of the Institute of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies, which operates within the research council. This kind of technology is well suited for today’s large-scale farms, he adds.

For large fields, the drone swarms could operate in relay teams, with drones landing and being replaced by others.

Or, farm co-ops could also buy swarms to share. The swarms don’t fly over a field daily, despite how fast it feels weeds grow. Smaller farms could adjust the number of drones they’d use depending on the size of their fields, Trianni says.

“Robot swarms can be scaled to exactly fit different farm sizes,” he adds.

Thanks to their communication capabilities, the drones will attract each other to a particularly weed-infested area. This means that very weedy patches are the first to be mapped and sent to those responsible for working the land, with less weedy areas next on the list, Trianni says.

“This is similar to swarms of bees that forage the most profitable flower patches,” he adds. “In this way, the planning of weed control activities can be limited to high-priority areas, hence generating savings while increasing productivity.”

The most common way currently to control weeds is to spray entire fields with herbicide chemicals. Smarter spraying will save farmers money and it will lower the risk of agrichemical resistance.

Of course, there’s a big environmental benefit from spraying fewer herbicides, Trianni adds.

Following the mapping by the bees, a swarm of the quadcopters could be released over a field. They’d stay in radio contact with each other and use algorithms learned from the bees to cooperate and put together a map of weeds.

This will then allow for targeted spraying of weeds or their mechanical removal on organic farms.

Quadcopters are small helicopters lifted and propelled by four rotors. Their miniature size—about the size of a child’s toy drone—makes them relatively inexpensive and allows them to fly in swarms, perfect for applications that Trianni and his team anticipate. The drones also avoid soil compaction and can act only where needed, Trianni says.

We’ll be seeing more of these robotic-enabled drone swarms in the future, as the price of robotics hardware lowers and miniaturization and the capabilities of robots increase, Trianni says. Swarm robots, which work in large groups, are an obvious use of these trends, he adds.

Swarms of drone robots haven’t typically been looked at for agricultural applications, though the pairing is a natural, he adds.

“We will soon be able to automate solutions to the level of the individual plant,” he says. “This needs to be accompanied by the ability to work in large groups, so as to efficiently cover big fields and work in synergy. Swarm robotics offers solutions to such a problem.”

Jean Thilmany is an independent writer.

In this way, the planning of weed control activities can be limited to high-priority areas, hence generating savings while increasing productivity.Vito Trianni, Italian National Research Council