Mobile Designs Are Expected Now

Mobile Designs Are Expected Now

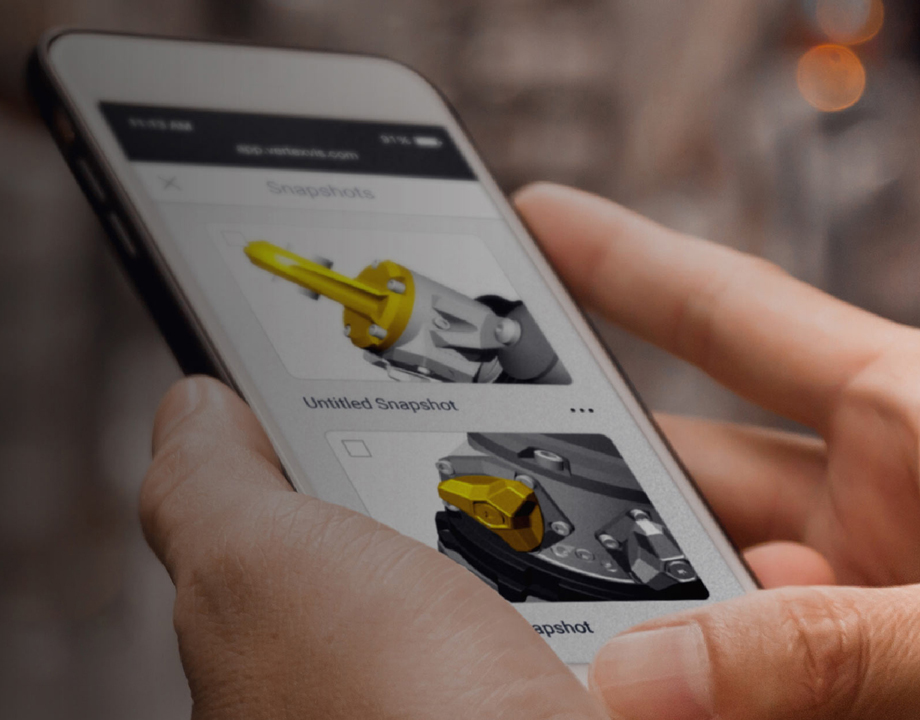

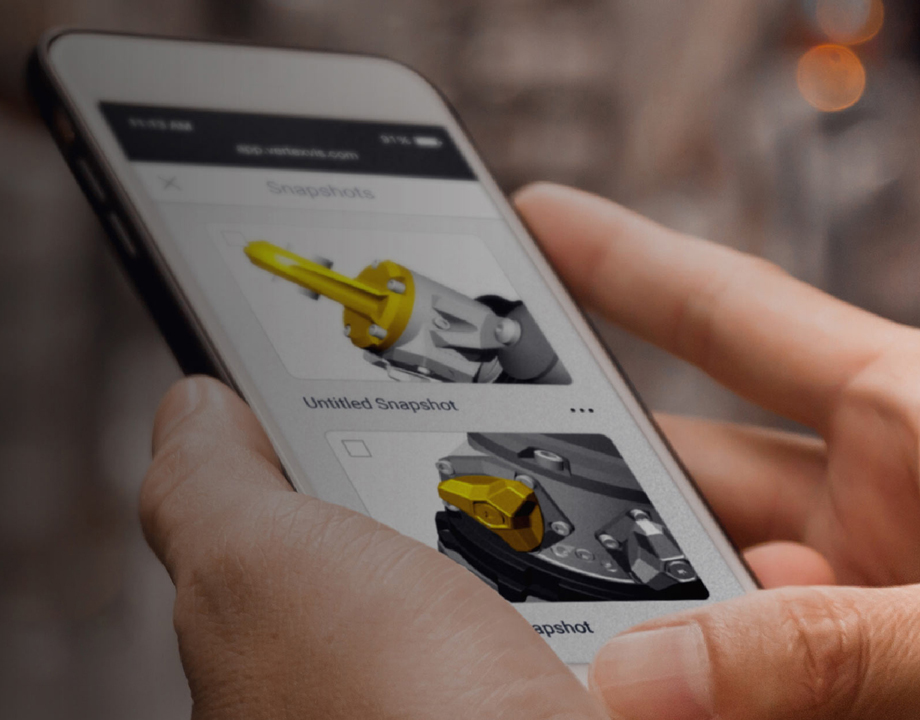

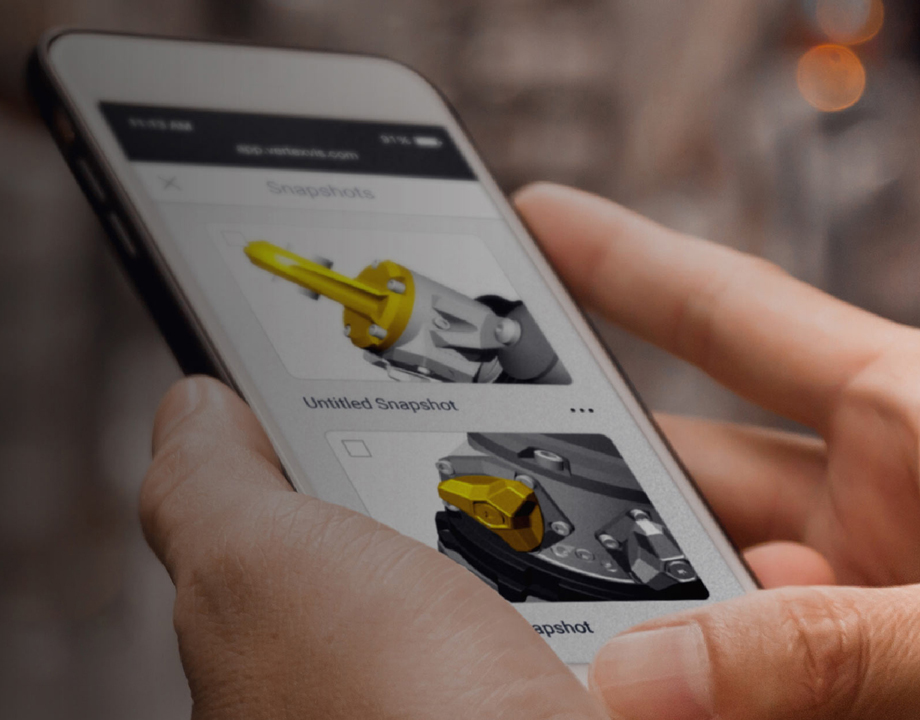

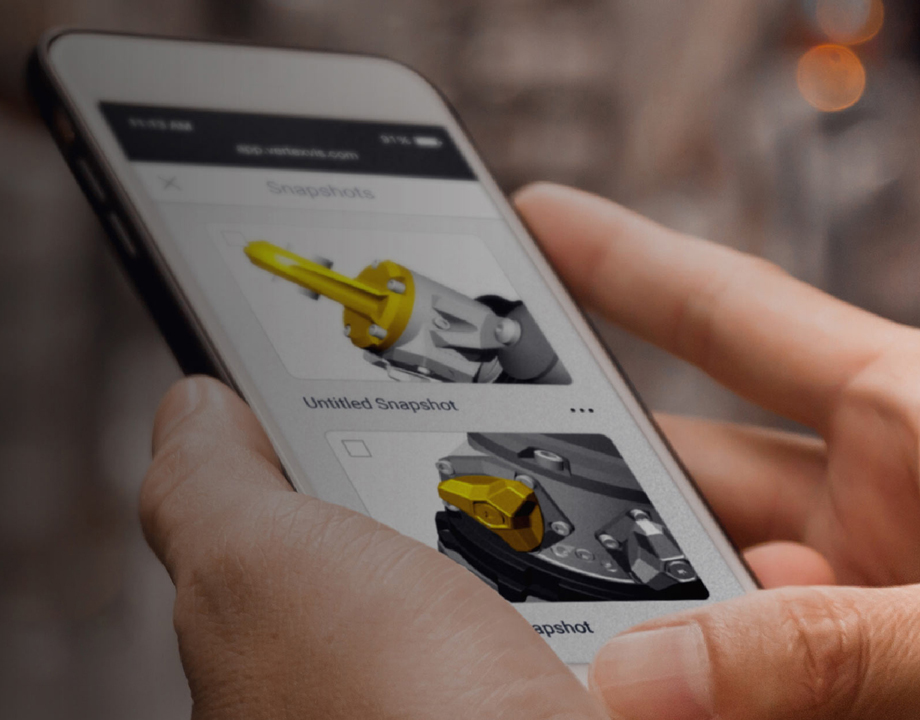

Younger workers expect technical drawings on smartphones. Photo: Vertex

It’s often hard for nonengineers at manufacturing facilities to really understand the two-dimensional drawings with which they’re routinely presented. Yet, for many years, three-dimensional product data remained locked inside computer-aided design systems, and couldn’t be accessed by those on the manufacturing floor or marketing department without CAD access.

That’s changing with the advent of new technology that pushes computer designs to those who need them.

And, because marketers and manufacturers aren’t desktop-bound these days, those designs can now be accessed on mobile devices like tablets and smartphones. That type of accessibility is vital for young workers who are used to having immediate access to anything they want to know.

For them, 2-D assembly instructions mean nothing other than outdated operations, according to Dan Murray, chief executive officer at Vertex. The company takes CAD information into the cloud and turns it into renderings.

This next generation of workers have used technology their entire lives, and they expect to do so on the job. They take information access for granted and expect quick answers and instant, open communication with colleagues, Murray said.

“When they’re off the job, younger workers are tied to their smartphones. That’s just the way it is. This generation expects that mobile devices and applications will exist in the workspace,” he said. “They expect their technology to be always with them, so they can call up information in seconds and communicate quickly with colleagues.”

Editor’s Pick: AI and Optimization: A Meeting of the Minds

The Vertex rendering software allows CAD models—no matter how intricate—to be available on tablets and even smartphones, Murray said. The models and information is also accessible across business systems like enterprise resource planning, the product lifecycle management, and marketing.

Albert Finley, who works in manufacturing at the John Deere manufacturing plant in Dubuque, Iowa, confirmed Murray’s take on this young generation of workers.

“I can’t even image looking at some type of blueprints,” he said. “I probably wouldn’t want to stay on that job for long. I never studied mechanical drawing in high school or anything.”

And yes, he carries his smartphone with him everywhere and typically uses it for work.

More for You: Can Software Help Identify Additive Manufacturing Prospects

Finley recently helped clear his grandfather’s belongings from a home they had lived in for sixty years. He found numerous books on industrial and mechanical drawing, as his grandfather had been a mechanical engineer.

“Looking at them, I’m glad we’ve moved on to images that look like an actual part,” he said.

CAD information can, in actuality, be pushed out to nondesigners, but that process came with a pretty significant drawback. CAD models had to be translated before they can be used by other software systems across the company, a cumbersome process. And those detailed models were only available via desktop computers.

“Access to 3-D models and product data has been a major barrier for cross-functional teams for decades,” Murray said.

Take the example of Terex Utilities, which makes lifting and handling equipment for utility and other companies. Products include the aerial devices, digger derricks, and auger drills used at electrical utilities to repair, string, or lay power lines. These are usually large, expensive machines. They are often customized to order with unique design details, said Kyle Wiesner, Terex engineering manager.

When salespeople took their images into the field, customers didn’t really understand the 2D drawings that depicted how the equipment could be customized. That meant they inadvertently overlooked important design changes they wanted to make and meant rework costs for Terex, Wiesner said.

During sales, 2-D drawings couldn’t help potential customers envision the final product, much less the dimensions of it, like, for instance, the length of the truck bed.

The company began using Vertex software in 2019.

Reaer’s Choice: Open-Source Software Boosts Quadrapedal Robots

Customers now receive an interactive, 3D version of the product to easily understand and provide more valuable feedback quicker. That capability alone reduced final-equipment error rates by 20 percent, Wiesner said.

Finley isn’t necessarily concerned with sales numbers, as he doesn’t work in sales. Though he does say mobile devices plays a big part in his own buying habits.

“I pretty much buy everything on the internet these days,” he said. “And I would really need to see a view of the product on my phone.

At work, he does refer to his smartphone to at pertinent product models several times a day.

“I know that makes work and personal blur together, but I think we all expect that these days,” he said. “I’m not phased by that at all.”

Jean Thilmany is a science and technology writer in Saint Paul, Minn.

That’s changing with the advent of new technology that pushes computer designs to those who need them.

And, because marketers and manufacturers aren’t desktop-bound these days, those designs can now be accessed on mobile devices like tablets and smartphones. That type of accessibility is vital for young workers who are used to having immediate access to anything they want to know.

For them, 2-D assembly instructions mean nothing other than outdated operations, according to Dan Murray, chief executive officer at Vertex. The company takes CAD information into the cloud and turns it into renderings.

This next generation of workers have used technology their entire lives, and they expect to do so on the job. They take information access for granted and expect quick answers and instant, open communication with colleagues, Murray said.

“When they’re off the job, younger workers are tied to their smartphones. That’s just the way it is. This generation expects that mobile devices and applications will exist in the workspace,” he said. “They expect their technology to be always with them, so they can call up information in seconds and communicate quickly with colleagues.”

Editor’s Pick: AI and Optimization: A Meeting of the Minds

The Vertex rendering software allows CAD models—no matter how intricate—to be available on tablets and even smartphones, Murray said. The models and information is also accessible across business systems like enterprise resource planning, the product lifecycle management, and marketing.

Albert Finley, who works in manufacturing at the John Deere manufacturing plant in Dubuque, Iowa, confirmed Murray’s take on this young generation of workers.

“I can’t even image looking at some type of blueprints,” he said. “I probably wouldn’t want to stay on that job for long. I never studied mechanical drawing in high school or anything.”

And yes, he carries his smartphone with him everywhere and typically uses it for work.

More for You: Can Software Help Identify Additive Manufacturing Prospects

Finley recently helped clear his grandfather’s belongings from a home they had lived in for sixty years. He found numerous books on industrial and mechanical drawing, as his grandfather had been a mechanical engineer.

“Looking at them, I’m glad we’ve moved on to images that look like an actual part,” he said.

CAD information can, in actuality, be pushed out to nondesigners, but that process came with a pretty significant drawback. CAD models had to be translated before they can be used by other software systems across the company, a cumbersome process. And those detailed models were only available via desktop computers.

“Access to 3-D models and product data has been a major barrier for cross-functional teams for decades,” Murray said.

Take the example of Terex Utilities, which makes lifting and handling equipment for utility and other companies. Products include the aerial devices, digger derricks, and auger drills used at electrical utilities to repair, string, or lay power lines. These are usually large, expensive machines. They are often customized to order with unique design details, said Kyle Wiesner, Terex engineering manager.

When salespeople took their images into the field, customers didn’t really understand the 2D drawings that depicted how the equipment could be customized. That meant they inadvertently overlooked important design changes they wanted to make and meant rework costs for Terex, Wiesner said.

During sales, 2-D drawings couldn’t help potential customers envision the final product, much less the dimensions of it, like, for instance, the length of the truck bed.

The company began using Vertex software in 2019.

Reaer’s Choice: Open-Source Software Boosts Quadrapedal Robots

Customers now receive an interactive, 3D version of the product to easily understand and provide more valuable feedback quicker. That capability alone reduced final-equipment error rates by 20 percent, Wiesner said.

Finley isn’t necessarily concerned with sales numbers, as he doesn’t work in sales. Though he does say mobile devices plays a big part in his own buying habits.

“I pretty much buy everything on the internet these days,” he said. “And I would really need to see a view of the product on my phone.

At work, he does refer to his smartphone to at pertinent product models several times a day.

“I know that makes work and personal blur together, but I think we all expect that these days,” he said. “I’m not phased by that at all.”

Jean Thilmany is a science and technology writer in Saint Paul, Minn.