A New Spin on Vinyl Records

A New Spin on Vinyl Records

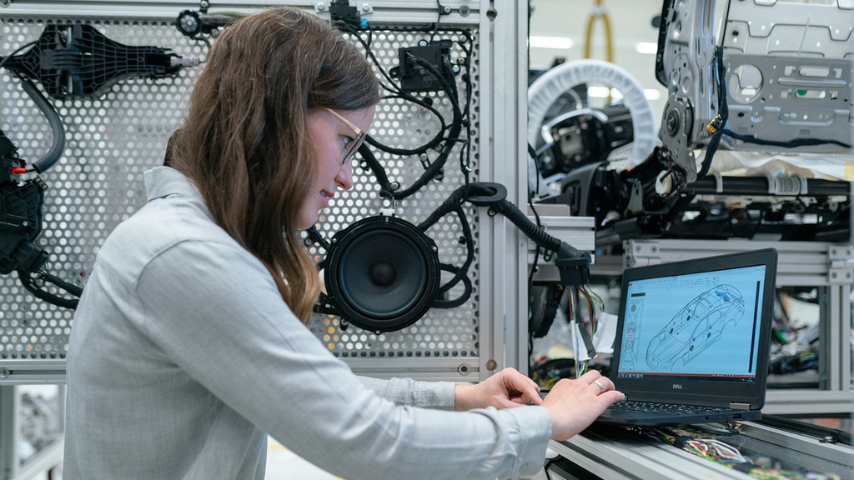

A 3D printed record. Image: amandaghassaei.com

In a classic case of what goes around comes around, old-school vinyl record albums are suddenly back in heavy rotation. Pushed aside by newer, supposedly superior digital-age formats like compact discs and MP3s, vinyl discs are selling – and making money – at rates not seen since 1988.

On the surface, the vinyl revival is a welcome bright spot for a beleaguered recording industry. On the flip side, there’s a pressing problem – literally. Only a handful of record-pressing plants remain in operation, and they must cope with aging, difficult-to-service machinery, a shortage of skilled labor, and a raw materials supply controlled by a single company. But in the meantime, additive manufacturing technology has advanced to a level of precision that could create interesting possibilities for this niche application. Can engineers harness the twin revolutions in 3D printing and vinyl recording to get LPs back in the groove? At least one Maker has given it a spin.

The Maker Behind the Music

Amanda Ghassaei, a former editorial staffer at Instructables and current grad student in the Center for Bits and Atoms at MIT’s Media Lab, has developed a workflow to convert digital audio files into 3D printed records that can be played on an ordinary turntable. Her first effort, a lo-fi approximation of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” first made waves in 2012. The sound quality may evoke memories of the Kenner Close-n-Play phonograph, or a fuzzy AM radio signal from a far-off station, but beneath that layer of noisy imperfection, the song is more than recognizable. She has gone on to print a number of songs, and her conversion algorithm was used to print the world’s first original song to be released on a 3D printed record: Down Boy, a 12-inch vinyl single by British electronic dance-pop artists Kele Okerefe and Bobbie Gordon.

Ghassaei, whose stated passion is developing tools that help people think, work and play more creatively, said the project was mainly a test of the limits of 3D printing technology. But now that vinyl revenues are growing by 50 percent a year, her experiments may point to a new future for record production.

Why Vinyl?

The vinyl revival “continues to befuddle even the most astute industry observers,” blogged Record Industry Association of America executives Josh Friedlander and Cara Duckworth Weiblinger. “Vinyl remains a niche but it’s not insignificant.” The 17 million vinyl albums sold last year is paltry compared to the multiple billions of songs listeners streamed for “free” on advertising-supported services. Yet those records generated some $416 million, surpassing revenues from on-demand streaming for the first time, the RIAA reports.

Vinyl records never totally disappeared. A disparate group of aficionados has clung to the format, and each sub-group has its own reasons. Hardcore audiophiles and electronic music fans use words like “warm” and “immersive” to describe vinyl’s unique aural allure. Sampling from vinyl LPs has long been a mainstay of the hip hop genre. And a persistent interest in the retro music, fashions, and lifestyles of the 1940s-60s is luring mid-century-modern hipsters back to record stores. Suddenly vintage-style record players are on the shelves of Target and Walmart next to a gallery of new and re-released vinyl albums from groups ranging from Black Sabbath to the White Stripes. Music industry magazine Billboard views the 32% annual increase in turntable sales as a key indicator of vinyl’s staying power: “fans who invest in the gear tend to buy records.”

So what’s stopping the industry from cashing in on this unexpected new market? Infrastructure. Compared to the automated mass production of CDs, the manufacture of a vinyl record involves numerous discrete steps such as electroplating that require hand work by skilled professionals. Many of those workers and their sophisticated machines were idled during the industry’s shift to CDs. Surviving pressing plants must get their LP-quality vinyl lacquers from one company that controls 90% of the world supply. Hence new artists today can expect to wait four or more months for a record to be pressed, often taking a back seat in the production queue to higher priority re-issues of classic blockbuster albums. If the vinyl revival is here to stay, the industry either faces a daunting re-investment in a technology of yesteryear – or an equally big commitment to modernization and automation. Are Amanda Ghassaei’s noisy 3D printed records an indicator of what’s to come?

A Groovy Workflow

As Ghassaei documents on the Instructables website, her method converts any digital audio file format into a 3D model of a traditional vinyl disc that can be printed and played back on an ordinary turntable. Because the 3D modeling challenge was too advanced for standard drafting-style CAD techniques, she wrote her own program to import raw audio files, calculate the 3D geometry of a record album, and export that geometric data into a 3D-printable file format. She used an open-source programming environment called Processing to handle most of the 3D modeling chores.

Only by pushing the resolution limits of today’s most precise resin printers could she attempt to approximate the grooves of an actual record. She used a Stratasys (Eden Prairie, MN) Object Connex 500 UV-cured resin printer capable of 600 dpi resolution in the x and y axes and 16-micron resolution in the z axis. Still, she said, the finished product is “an order of magnitude or two away from the resolution of a real vinyl record.” The resulting wide grooves on the record surface explain why a five-minute song like “Smells Like Teen Spirit” consumes an entire side of a 3D-printed LP album. As she explains, it’s similar to Thomas Edison’s results from his early phonographs and record-cutting machines, where the technological limits of the time produced wide-grooved records we would consider unacceptably noisy today.

No one yet believes 3D printed records will be ready for primetime any time soon, but there’s a clear harmony between the technology and this resilient audio format. “It’s never going to be as good as vinyl,” Ghassaei said, “but it’s really cool because you can be really creative with it.”

Michael MacRae is an independent writer.

Learn more about the latest trends in 3D printing at ASME’s AM3D Conference & Expo.

It’s never going to be as good as vinyl. But, it’s cool because you can really be creative with it.Amanda Ghassaei, Instructables