Engine Becomes a Chemical Reactor

Engine Becomes a Chemical Reactor

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have repurposed an automobile engine to convert otherwise leaked methane into liquid fuels.

Methane is the main component of natural gas and a precursor to several important chemicals. However, because methane is expensive to capture and process, companies often “flare” their methane at sites where it is an industrial byproduct. That’s bad, though not as bad as letting the methane leak into the atmosphere, where it acts as a potent greenhouse gas.

What would be better is finding an efficient way to process the methane byproduct onsite. With an innovative idea in mind, two former Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineers—Emmanuel Kasseris and Leslie Bromberg—formed Emvolon, a startup with the goal of repurposing automotive engines to process methane into liquid fuels.

"We saw this as a new way of chemical manufacturing,” Kasseris said. “One day Leslie and I were discussing how expensive process equipment was in the chemical industry. A process vessel was more expensive than a car, even though it had less material and less manufacturing than a car. ‘Well then, let’s use a car engine for processes!’ was Leslie’s response.”

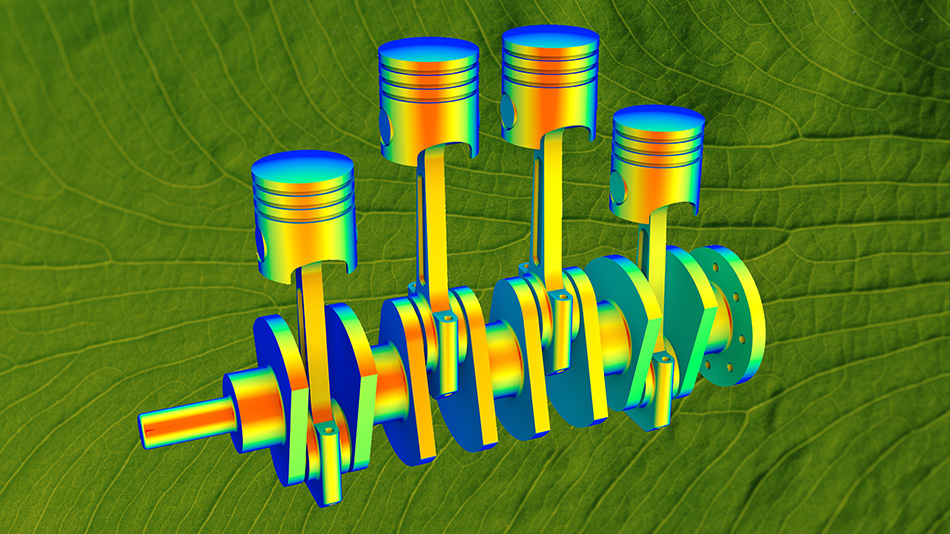

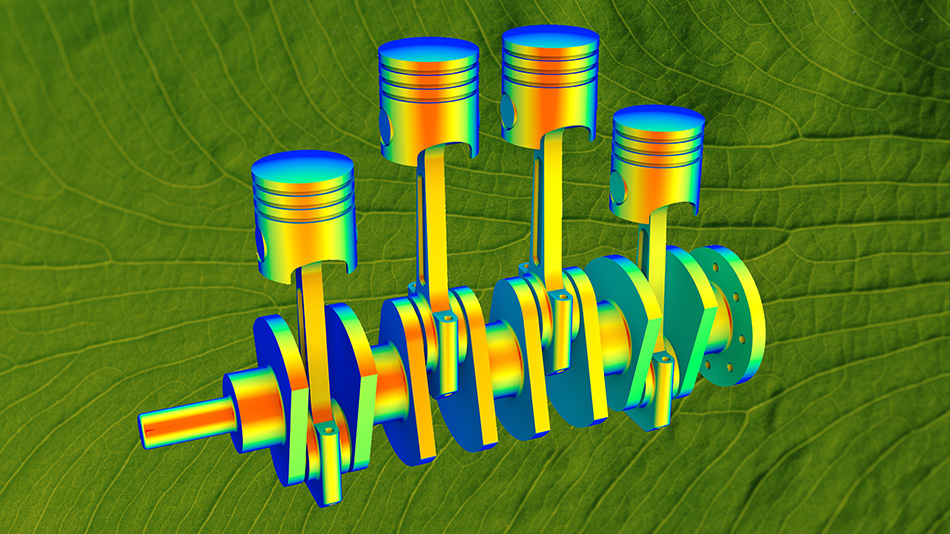

The reciprocating internal combustion engine has been traditionally used to convert chemical energy to mechanical power. Kasseris and Bromberg’s idea is to run the engine slightly differently, using the crankslider mechanism of the reciprocating engine to create the necessary pressure and temperature conditions to perform chemical reactions rather than combustion.

“Our goal was to convert our reactants into products as efficiently as possible and at the right concentrations,” Kasseris said. “This is a very challenging task, as it relies on precisely controlled pressure, temperature, and power absorbed and released, at thousands of revolutions per second.”

At the core of Emvolon’s system is an off-the-shelf automotive engine that runs “fuel rich”—with a higher ratio of fuel to air than what is needed for complete combustion.

“We are effectively operating an engine as a partial oxidation reactor,” Kasseris said.

“We are effectively operating an engine as a partial oxidation reactor,” Kasseris said.

Methane serves as the feed gas, introduced into the internal combustion engine-based chemical reactor. The engine is operated fuel rich in order to generate carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2), as well as power, instead of burning the methane to completion, which would make carbon dioxide and water.

More Like This: Using Thermoelectric Generators for Carbon-Free Fuels and Chemicals

The CO and H2 can also be used to synthesize chemicals in a subsequent step. “The trick, which is a good part of our intellectual property, is in the controls that ensure the engine keeps running reliably under these fuel-rich conditions, which can be quite challenging,” Kasseris said. The engine reactor must be operated while ensuring the feed fuel is converted into high-quality synthesis gas (CO and H2), without methane slipping or making soot while the engine reactor keeps running, with varying inlet flow and composition.

Zero-carbon-emission biofuels will play an increasingly important role at processing sites, powering waste management systems, vehicles, power generation facilities, and agricultural equipment. For marine and aviation applications, the portable internal combustion-engine-based chemical reactor can be deployed at docks and airplane hangars, enabling on-site production of sustainable fuel for maritime and aviation fleets.

“Our whole process was designed to be a very realistic approach to the energy transition,” Kasseris said. “Our solution is designed to produce green fuels and chemicals at prices that the markets are willing to pay today, without the need for subsidies.”

For You: New Filter Fights Forever Chemicals

Furthermore, Emvolon’s modular systems require small investments (less than $10 million) and can be deployed within a matter of weeks. Unit capacities range from a few tons to a few tens of tons per day for converting distributed (biogas, biomass, municipal waste) and variable (renewable) resources needed to make green fuels.

The company is developing its platform technology so it can convert green hydrogen and nitrogen into green ammonia, as well as the synthesis of green methanol from green hydrogen and carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide.

“We’d like to expand to other chemicals, and other feedstocks as well, such as biomass and hydrogen from renewable electricity, and we already have promising results in that direction,” Kasseris said. “We think we have a good solution for the energy transition and, in the later stages of the transition, for e-manufacturing.”

Mark Crawford is a technology writer in Corrales, N.M.

What would be better is finding an efficient way to process the methane byproduct onsite. With an innovative idea in mind, two former Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineers—Emmanuel Kasseris and Leslie Bromberg—formed Emvolon, a startup with the goal of repurposing automotive engines to process methane into liquid fuels.

"We saw this as a new way of chemical manufacturing,” Kasseris said. “One day Leslie and I were discussing how expensive process equipment was in the chemical industry. A process vessel was more expensive than a car, even though it had less material and less manufacturing than a car. ‘Well then, let’s use a car engine for processes!’ was Leslie’s response.”

The reciprocating internal combustion engine has been traditionally used to convert chemical energy to mechanical power. Kasseris and Bromberg’s idea is to run the engine slightly differently, using the crankslider mechanism of the reciprocating engine to create the necessary pressure and temperature conditions to perform chemical reactions rather than combustion.

“Our goal was to convert our reactants into products as efficiently as possible and at the right concentrations,” Kasseris said. “This is a very challenging task, as it relies on precisely controlled pressure, temperature, and power absorbed and released, at thousands of revolutions per second.”

At the core of Emvolon’s system is an off-the-shelf automotive engine that runs “fuel rich”—with a higher ratio of fuel to air than what is needed for complete combustion.

Can We Engineer Safer Sports?

Millions of sports injuries occur each year at every level. Sports engineers are finding innovative ways to redesign sports equipment to help reduce that number.

Methane serves as the feed gas, introduced into the internal combustion engine-based chemical reactor. The engine is operated fuel rich in order to generate carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2), as well as power, instead of burning the methane to completion, which would make carbon dioxide and water.

More Like This: Using Thermoelectric Generators for Carbon-Free Fuels and Chemicals

The CO and H2 can also be used to synthesize chemicals in a subsequent step. “The trick, which is a good part of our intellectual property, is in the controls that ensure the engine keeps running reliably under these fuel-rich conditions, which can be quite challenging,” Kasseris said. The engine reactor must be operated while ensuring the feed fuel is converted into high-quality synthesis gas (CO and H2), without methane slipping or making soot while the engine reactor keeps running, with varying inlet flow and composition.

Mobile reactor

Emvolon has already built a system capable of producing up to six barrels of green methanol a day in its 5,000 square-foot headquarters in Woburn, Mass. The company’s standalone systems are designed to fit in a 40-foot shipping container and could produce as much as 8 tons of methanol per day from 300,000 standard cubic feet of methane gas.Zero-carbon-emission biofuels will play an increasingly important role at processing sites, powering waste management systems, vehicles, power generation facilities, and agricultural equipment. For marine and aviation applications, the portable internal combustion-engine-based chemical reactor can be deployed at docks and airplane hangars, enabling on-site production of sustainable fuel for maritime and aviation fleets.

“Our whole process was designed to be a very realistic approach to the energy transition,” Kasseris said. “Our solution is designed to produce green fuels and chemicals at prices that the markets are willing to pay today, without the need for subsidies.”

For You: New Filter Fights Forever Chemicals

Furthermore, Emvolon’s modular systems require small investments (less than $10 million) and can be deployed within a matter of weeks. Unit capacities range from a few tons to a few tens of tons per day for converting distributed (biogas, biomass, municipal waste) and variable (renewable) resources needed to make green fuels.

The company is developing its platform technology so it can convert green hydrogen and nitrogen into green ammonia, as well as the synthesis of green methanol from green hydrogen and carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide.

“We’d like to expand to other chemicals, and other feedstocks as well, such as biomass and hydrogen from renewable electricity, and we already have promising results in that direction,” Kasseris said. “We think we have a good solution for the energy transition and, in the later stages of the transition, for e-manufacturing.”

Mark Crawford is a technology writer in Corrales, N.M.