Making the Emotional Robot

Making the Emotional Robot

The robots that assemble our cars, that mow our lawns, and that take our orders at Pizza Hut are heartless, logical creatures, if, admittedly, sometimes cute. Unlike the humans they serve, they don’t respond to the events and interactions around them with joy, frustration, anger, sadness, or any of the other subtle feelings that accompany our species through life. Though artificial intelligence and neural networks are making robots smarter and more autonomous every day, robots are not likely to seem human—and make decision like humans—until they feel emotion.

Patrick Levy-Rosenthal, founder and CEO of EmoShape, has created a chip that will add the emo to the robo. With it, robots—as well as virtual reality and game characters, and smart rooms—will be able to read the emotions exhibited by users and react, respond, and make choices in emotionally appropriate ways.

For You: Read about new robotic breakthroughs from ASME.org.

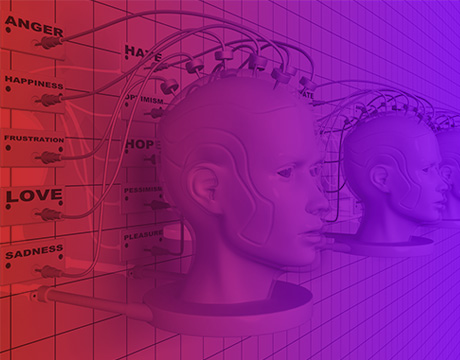

The company’s Emotional Processing Unit, as their chip is called, takes an input and converts it to twelve different waves based on the essential components of emotion: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, indifference, regret, surprise, anticipation, trust, confidence, desire, and joy. “The stimuli creates waves in the chip that interact with each other,” he says. “The result is the emotional state of the machine.”

By hooking up these twelve waves to actuators in the face of a robot, or pixels of an animation, the virtual emoter can become as expressive and subtle as flesh and blood. The chip’s “wave computing,” as Levy-Rosenthal calls it, is capable of producing 64 trillion possible emotions in a tenth of a second.

As a proof of concept, the company has created a virtual woman named Rachel that uses the chip. Right now she is just a face on a computer screen, hooked up to the chip and a simple AI program. But when she’s asked a question she truly comes alive.

“When we say to the system, ‘You look very nice today,’ she expresses happiness, confidence, and a bit of surprise,” Levy-Rosenthal says. That combinationon Rachel’s face looks very much like how a bonafide human might react to such a compliment. But, like a human, her response is not exactly the same every time. “Her first response is happiness. But if you repeat it three times, she starts to get annoyed.”

It’s this ability to learn and adapt that will make robots, voice assistants like Siri and Alexa, and gaming creatures, truly customizable. The chips can learn how to react not only to their owners’ preferences but also to their value systems. “The first time I said, ‘Hey, you look sexy,’ it didn’t react,” Levy-Rosenthal says. “If I say, ‘Rachel, sexy is good,’ the next time I say, ‘Hey Rachel, you’re sexy,’ she’ll smile right back—it makes her happy.”

Working with an AI program that can search the internet, the chip can learn how a human feels about social issues, specific politicians, Brussels sprouts, and anything else. “When the robot does something for the human and the human shows displeasure, the robot feels pain and wants to avoid it in the future,” Levy-Rosenthal says. “In a million robots, every single robot will start to diverge in relation to its human relations.”

Anyone can get a definition of racism on Wikipedia, but if I ask how you feel about it, that is what’s valuable to me. Patrick Levy-Rosenthal, founder and CEO, EmoShape

Creating personalized emotive robots is not just an effort to bring us closer to our sci-fi android fantasies. Levy-Rosenthal believes his chip will also make the workplace more productive, and a bit more pleasant.

“If a human and a robot are working together and the human feels bad and the robot doesn’t feel it, and continues at the same speed of production, the human will feel frustrated, the robot will have to slow down, there’s a bottleneck, productivity slows down, the human takes a baseball bat and smashes the robot,” he says. “It’s not what you want.”

Whatever the chip’s productivity enhancement potential, it will surely humanize human-robot interactions. As Levy-Rosenthal likes to point out, we understand with more than our intellect.

“We don’t just ask each other ‘What is this or what is that,’ but ‘What do you think and what do you feel about it,’ ” he says. “This is the beauty of human interaction. Anyone can get a definition of racism on Wikipedia, but if I ask how you feel about it, that is what’s valuable to me.”

Michael Abrams is an independent writer.

Read More:

Snake Robots Crawl to the Rescue

Remote Robot Cleans Trash from Water

Robots Modeled on Bees Sense Rather than Think