Researchers 3D Print on Skin for Breakthrough Applications

Researchers 3D Print on Skin for Breakthrough Applications

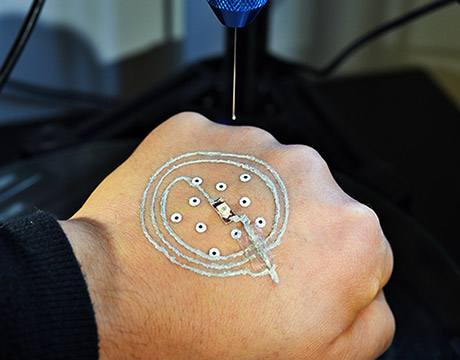

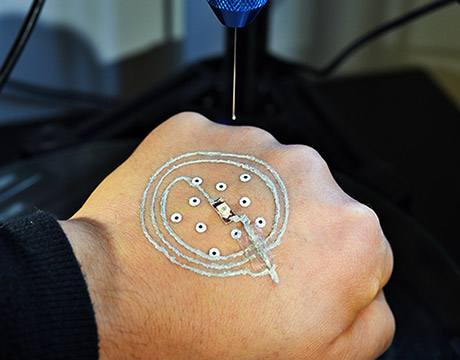

Researchers at the University of Minnesota use a customized 3D printer to print electronics on a real hand. Image: McAlpine group, University of Minnesota

Soldiers are commonly thrust into situations where the danger is the unknown: Where is the enemy, how many are there, what weaponry is being used? The military already uses a mix of technology to help answer those questions quickly, and another may be on its way. Researchers at the University of Minnesota have developed a low-cost 3D printer that prints sensors and electronics directly on skin. The development could allow soldiers to directly print temporary, disposable sensors on their hands to detect such things as chemical or biological agents in the field.

The technology also could be used in medicine. The Minnesota researchers successfully used bioink with the device to print cells directly on the wounds of a mouse. Researchers believe it could eventually provide new methods of faster and more efficient treatment, or direct printing of grafts for skin wounds or conditions.

“The concept was to go beyond smart materials, to integrate them directly on to skin,” says Michael McAlpine, professor of mechanical engineering whose research group focuses on 3D printing functional materials and devices. “It is a biological merger with electronics. We wanted to push the limits of what a 3D printer can do.”

McAlpine calls it a very simple idea, “One of those ideas so simple, it turns out no one has done it.”

Others have used 3D printers to print electronics and biological cells. But printing on skin presented a few challenges. No matter how hard a person tries to remain still, there always will be some movement during the printing process. “If you put a hand under the printer, it is going to move,” he says.

To adjust for that, the printer the Minnesota team developed uses a machine vision algorithm written by Ph.D. student Zhijie Zhu to track the motion of the hand in real time while printing. Temporary markers are placed on the skin, which then is scanned. The printer tracks the hand using the markers and adjusts in real time to any movement. That allows the printed electronics to maintain a circuit shape. The printed device can be peeled off the skin when it is no longer needed.

The team also needed to develop a special ink that could not only be conductive but print and cure at room temperature. Standard 3D printing inks cure at high temperatures of 212 °F and would burn skin.

In a paper recently published in Advanced Materals, the team identified three criteria for conductive inks: The viscosity of the ink should be tunable while maintaining self-supporting structures; the ink solvent should evaporate quickly so the device becomes functional on the same timescale as the printing process; and the printed electrodes should become highly conductive under ambient conditions.

The solution was an ink using silver flakes to provide conductivity rather than particles more commonly used in other applications. Fibers were found to be too large, and cure at high temperatures. The flakes are aligned by their shear forces during printing, and the addition of ethanol to the mix increases speed of evaporation, allowing the ink to cure quickly at room temperature.

“Printing electronics directly on skin would have been a breakthrough in itself, but when you add all of these other components, this is big,” McAlpine says.

For you: 3D Printing Better Root Canals

The advantage of our approach is that you don’t have to start with electronic wafers made in a clean room. This is a completely new paradigm for printing electronics using 3D printing.Prof. Michael McAlpine, University of Minnesota

The printer is portable, lightweight and cost less than $400. It consists of a delta robot, monitor cameras for long-distance observation of printing states and tracking cameras mounted for precise localization of the surface. The team added a syringe-type nozzle to squeeze and deliver the ink

Furthering the printer’s versatility, McAlpine’s team worked with staff from the university’s medical school and hospital to print skin cells directly on a skin wound of a mouse. The mouse was anesthetized, but still moved slightly during the procedure, he says. The initial success makes the team optimistic that it could open up a new method of treating skin diseases.

“Think about what the applications could be,” McAlpine says. “A soldier in the field could take the printer out of a pack and print a solar panel. On the cellular side, you could bring a printer to the site of an accident and print cells directly on wounds, speeding the treatment. Eventually, you may be able to print biomedical devices within the body.”

In its paper, the team suggests that devices can be “autonomously fabricated without the need for microfabrication facilities in freeform geometries that are actively adaptive to target surfaces in real time, driven by advances in multifunctional 3D printing technologies.”

Besides the ability to print directly on skin, McAlpine says the work may offer advantages over other skin electronic devices. For example, soft, thin, stretchable patches that stick to the skin have been fitted with off-the-shelf chip-based electronics for monitoring a patient’s health. They stick to skin like a temporary tattoo and send updates wirelessly to a computer.

“The advantage of our approach is that you don’t have to start with electronic wafers made in a clean room,” McAlpine says. “This is a completely new paradigm for printing electronics using 3D printing.”

Read more:

3D Painting Structures in Space

3D Printing Technologies Rise to New Levels

New 3D Printer Extruder Takes Manufacturing to the Next Level