Technology Is the Future of Construction

Technology Is the Future of Construction

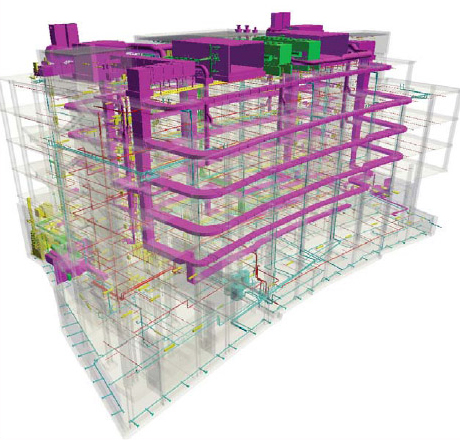

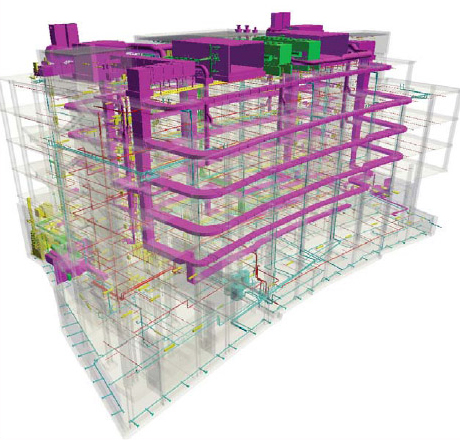

Benjamin D. Hall Interdisciplinary Research Building at the University of Washington, © M.A. Mortenson Company

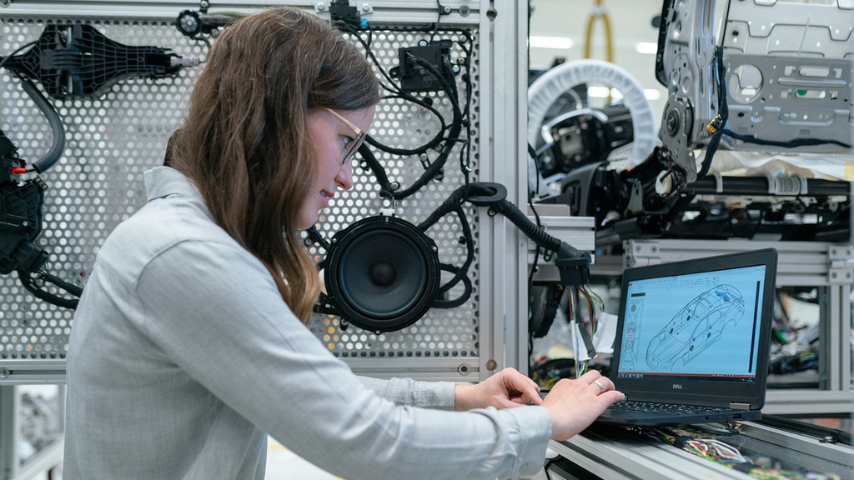

Thanks to improved technologies, mechanical engineering in construction has found itself more efficient and, at the planning stage, cheaper.

Richard Beattie, a mechanical engineer and president of MEC² in Baltimore, MD, says the industry is moving toward BIM—building information modeling—a collaborative design between the architect structure which allows designing in 4D.

“You identify conflicts on the same documents so we can work collaboratively, allowing people in the field to see the building,” he says. “You see everything in 2D when you look at drawings—it’s in the plan view, like looking at the floor plan of your house. That’s how construction has been done for 100 years but you can’t see depth so when you have confined space you don’t know if something designed would hit the sprinkler, pipe or HVAC duct.”

Previously, you had to wait for the architect of the drawing then have a structural person see how the floor would be. That kind of coordination doesn’t happen at the design level but has to happen at the field level and causes delays and overruns, Beattie says. “We say that if you put something on a drawing you have a 50% chance of getting it installed,” Beattie laughs. “But if you can show it in 3D you can get it up to 80–90%.”

Certification Issues

Beattie says one of the biggest issues is pushing green technology and LEED certification for buildings. In doing that, owners are looking for more accurate models.

“It means we develop computer models to predict performance of the building for electricity usage and gas usage,” Beattie says. “You can spend a year working on the models. But so many variables can predict the difference between two different systems that predicting actual usage of the building is hard to do. The challenge is refining a modeling of building so it would be accurate and keep up with changes in codes.”

Still, Beattie says it’s an exciting time in construction because “everything is energy-drive,” which only leads to more innovation. “Ten years ago, no house wanted to be first to put something in,” he says. “But now manufacturers give tons of new product to the marketplace. Owners want to differentiate their building and don’t want the same package. It’s a chance for cutting edge. From a control standpoint you don’t have to repeat cookie-cutter commodity designs. That makes it much more fun.”

Eric Butterman is an independent writer.

We say that if you put something on a drawing you have a 50 percent chance of getting it installed,” Beattie laughs. “But if you can show it in 3D you can get it up to 80–90 percent.Richard Beattie, MEC²