Engineers Design a Reusable Alternative to N-95 Face Mask

Engineers Design a Reusable Alternative to N-95 Face Mask

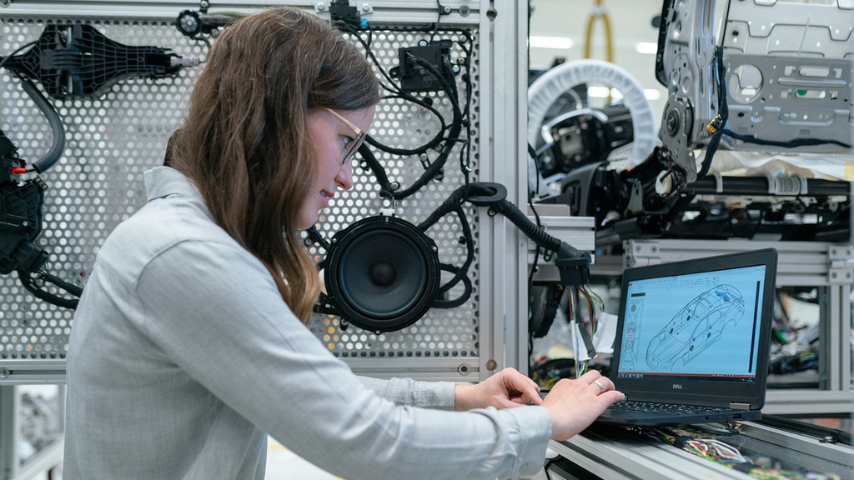

MIT researchers have developed reusable masks with filtering advantages of the N-95. Photo: Courtesy of the researchers

A shortage of N-95 masks continues to plague healthcare workers on the frontlines of the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. A research team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston has designed a silicone replacement that is just as efficient as the N-95 at filtering out droplets of water vapor carrying pathogens.

Any solution that replaces the N-95 has to meet a few basic criteria, said Giovanni Traverso, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s hospital. “Our initial focus was on reusability, sterilizability, comfort, and ability to be manufactured at scale,” Traverso said, of the research that started in late February 2020.

Early prototypes evaluated polypropylene for its ability to be autoclaved, but the team quickly settled on liquid silicone rubber. “Silicone is a fantastic material for its durability and high temperature and chemical resistance. Liquid silicone rubber has advantages in terms of comfort too,” said Adam Wentworth, senior research engineer at Brigham and an affiliate at Traverso’s MIT lab. Wentworth designed the mask in collaboration with James Byrne, senior radiation oncologist at the Brigham and postdoctoral associate at the Traverso lab.

The additional advantage of using silicone: Masks can be manufactured at scale using injection molding. Designing for injection molding is more forgiving, Wentworth points out. “It gives you an ability to accommodate concave surfaces and overhangs, so you get a little more design freedom,” he said. The Dow QP1-250, the polymer the team used in the first iteration, is the same one used for anesthesia masks, so they knew the material already had a proven application in mask design.

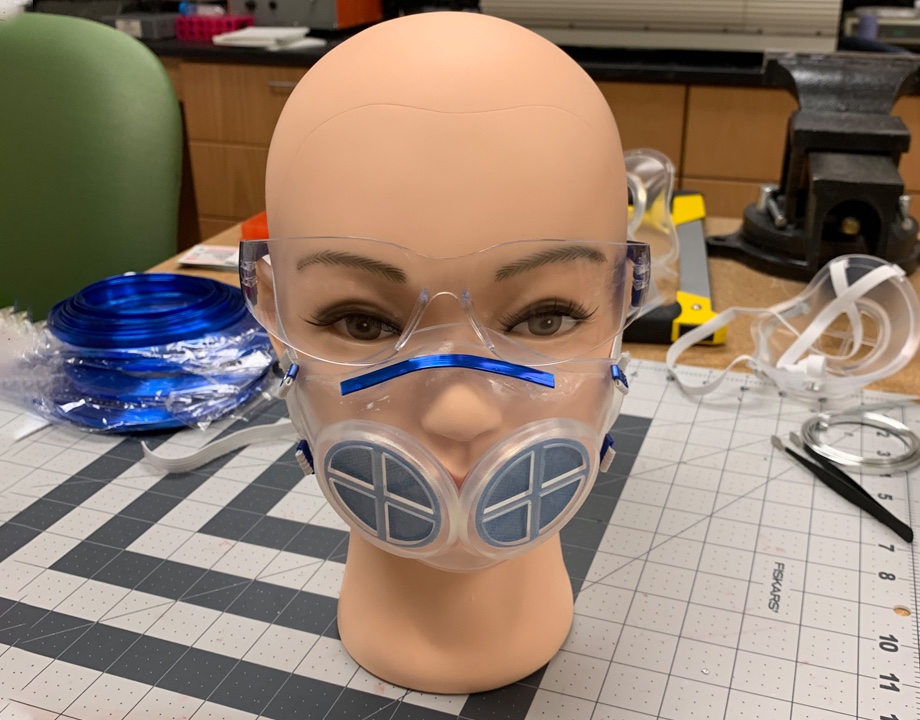

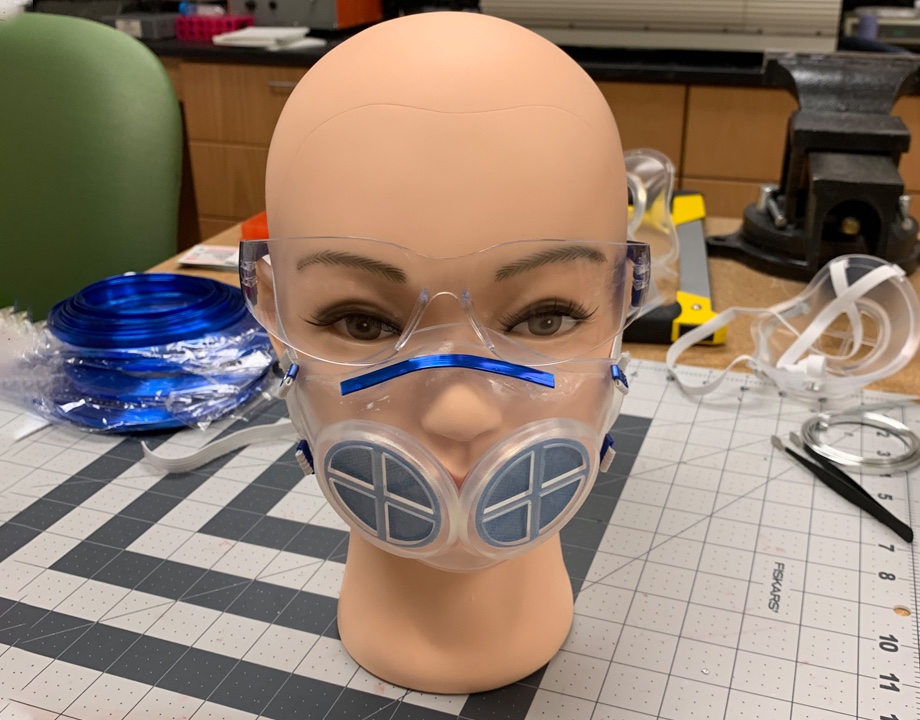

An added benefit of using liquid silicone rubber: near-transparent masks which facilitate lip-reading and establish better patient-physician rapport.

Initial prototypes led to a tight, fitted, clear elastomeric mask with N-95 pancake filters that can be sterilized, and the filters discarded after each use. Since users are discarding only the small discs, researchers expect supply to not be a major bottleneck. “We are evaluating several manufacturers that have suppliers in both domestic and international markets, and can scale quickly,” Wentworth said.

Editor’s Pick: Virus-Vanquishing Surface to Reduce Transmission

The team conducted clinical trials at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital and is currently working on a third version of the mask, applying lessons from field testing to inform better and more comfortable fit. “We have some great data in terms of biometric data in terms of visual and sensory incorporation,” said Byrne.

Injection molding is expensive, but the team expects masks’ costs to be low or comparable to that of the N-95 because the silicone equivalent can be sterilized and reused extensively. While the team doesn’t have a definite answer for how many times a single mask can be reused, members have tested the masks and components to get a sense that hundreds of uses are not unlikely.

While healthcare institutions like the Brigham and Women’s hospital have aerosolized hydrogen peroxide systems to sterilize N-95 masks, these systems are not readily available around the world. Accessibility and easy re-sterilization were other important criteria for the MIT masks. “We really wanted a system that could be sterilized anywhere, globally,” Traverso said.

Recommended for You: LIDAR for Remote Sensing During COVID-19

The silicone masks can be autoclaved and cleaned using dry or steam sterilization and can be disinfected using alcohol and wipes.

Elastomeric masks such as these made from silicone are more comfortable and provide a better seal on the face, Wentworth said. “The filtration efficiencies are really down to the filtration media and the area of the filters,” he adds. The designed mask meets the fit criteria from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) which factors in breathability and a 95 percent filtration efficiency.

The team conducted facial scans to understand different face shapes and determined that the masks can fit a variety of face shapes.

Future iterations of the mask design will evaluate alternative filtration materials and their environmental impact. Traverso has formed a company, Teal Bio, to work with contract manufacturers to produce the masks at scale. Fundraising and talks with the FDA are underway as are those with supply chain vendors.

Other research at the Traverso lab focuses on ingestible systems for drug delivery and drug administration in a single dose. “We do a lot of fundamental material science and prototype development for applications across the body,” Traverso said.

Explore More on What is the New Normal for Engineering Workplaces?

Resolving the N-95 mask shortage has been high-priority and Traverso believes they are on to a scalable solution that checks off all the boxes. “There aren’t that many materials that meet all the demands that we need from a reusable mask. When you think about all the needles that need to be threaded, liquid silicone rubber is really one that works,” Traverso said.

Poornima Apte is an independent writer based in Walpole, Mass.

Any solution that replaces the N-95 has to meet a few basic criteria, said Giovanni Traverso, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s hospital. “Our initial focus was on reusability, sterilizability, comfort, and ability to be manufactured at scale,” Traverso said, of the research that started in late February 2020.

Early prototypes evaluated polypropylene for its ability to be autoclaved, but the team quickly settled on liquid silicone rubber. “Silicone is a fantastic material for its durability and high temperature and chemical resistance. Liquid silicone rubber has advantages in terms of comfort too,” said Adam Wentworth, senior research engineer at Brigham and an affiliate at Traverso’s MIT lab. Wentworth designed the mask in collaboration with James Byrne, senior radiation oncologist at the Brigham and postdoctoral associate at the Traverso lab.

Design Freedom

The additional advantage of using silicone: Masks can be manufactured at scale using injection molding. Designing for injection molding is more forgiving, Wentworth points out. “It gives you an ability to accommodate concave surfaces and overhangs, so you get a little more design freedom,” he said. The Dow QP1-250, the polymer the team used in the first iteration, is the same one used for anesthesia masks, so they knew the material already had a proven application in mask design.

An added benefit of using liquid silicone rubber: near-transparent masks which facilitate lip-reading and establish better patient-physician rapport.

Initial prototypes led to a tight, fitted, clear elastomeric mask with N-95 pancake filters that can be sterilized, and the filters discarded after each use. Since users are discarding only the small discs, researchers expect supply to not be a major bottleneck. “We are evaluating several manufacturers that have suppliers in both domestic and international markets, and can scale quickly,” Wentworth said.

Editor’s Pick: Virus-Vanquishing Surface to Reduce Transmission

The team conducted clinical trials at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital and is currently working on a third version of the mask, applying lessons from field testing to inform better and more comfortable fit. “We have some great data in terms of biometric data in terms of visual and sensory incorporation,” said Byrne.

Sterilization and Reuse

Injection molding is expensive, but the team expects masks’ costs to be low or comparable to that of the N-95 because the silicone equivalent can be sterilized and reused extensively. While the team doesn’t have a definite answer for how many times a single mask can be reused, members have tested the masks and components to get a sense that hundreds of uses are not unlikely.

While healthcare institutions like the Brigham and Women’s hospital have aerosolized hydrogen peroxide systems to sterilize N-95 masks, these systems are not readily available around the world. Accessibility and easy re-sterilization were other important criteria for the MIT masks. “We really wanted a system that could be sterilized anywhere, globally,” Traverso said.

Recommended for You: LIDAR for Remote Sensing During COVID-19

The silicone masks can be autoclaved and cleaned using dry or steam sterilization and can be disinfected using alcohol and wipes.

Elastomeric masks such as these made from silicone are more comfortable and provide a better seal on the face, Wentworth said. “The filtration efficiencies are really down to the filtration media and the area of the filters,” he adds. The designed mask meets the fit criteria from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) which factors in breathability and a 95 percent filtration efficiency.

The team conducted facial scans to understand different face shapes and determined that the masks can fit a variety of face shapes.

Scalable Solution

Future iterations of the mask design will evaluate alternative filtration materials and their environmental impact. Traverso has formed a company, Teal Bio, to work with contract manufacturers to produce the masks at scale. Fundraising and talks with the FDA are underway as are those with supply chain vendors.

Other research at the Traverso lab focuses on ingestible systems for drug delivery and drug administration in a single dose. “We do a lot of fundamental material science and prototype development for applications across the body,” Traverso said.

Explore More on What is the New Normal for Engineering Workplaces?

Resolving the N-95 mask shortage has been high-priority and Traverso believes they are on to a scalable solution that checks off all the boxes. “There aren’t that many materials that meet all the demands that we need from a reusable mask. When you think about all the needles that need to be threaded, liquid silicone rubber is really one that works,” Traverso said.

Poornima Apte is an independent writer based in Walpole, Mass.