Gelatin Fibers for Recyclable Textiles

Gelatin Fibers for Recyclable Textiles

A new type of biofiber, made from gelatin, can be dissolved and recycled in hot water.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, more than 11 million tons of textiles end up in landfills each year, the majority of which is discarded clothing. As the clothing industry looks for ways to become more sustainable, while also investing in new technologies to support “smart textiles,” or fabrics that include sensors or other embedded electronic components to interact with the environment in a predetermined way, engineers are hoping to develop new materials that can be easily recycled.

Enter gelatin fibers.

A research team from the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) has developed an inexpensive, do-it-yourself machine that can spin textile fibers made from the waste byproducts of the meat industry. Eldy Lázaro Vásquez, a graduate student at CU Boulder’s ATLAS Institute, said while some may look askance at the idea of gelatin—the stuff of JELL-O and grandma’s aspic as the basis for future hoodies and curtains—the biopolymer is well-suited to a variety of textile applications.

“It’s very versatile. I’ve been working with gelatin for years and we’ve made foams out of it, bioplastics out of it, and now we have made these fibers,” she said. “This is a huge waste byproduct of the meat industry. And the ability to use an existing waste stream and develop it into a new sustainable material is a very exciting thing.”

More for You: Lunar Settlements Could Be Made from Fabric

Of course, Lázaro Vásquez admitted, developing the right chemistry to make the right gelatin base for a textile fiber machine was a challenge. She spent a summer at the Institute for Advanced Textiles at Germany’s University of Aachen to learn more about how to successfully make fibers out of bio-based materials. It was there she learned how to take gelatin powder, sourced from the butcher, and prepare it into the right viscous solution that could form a reliable fiber.

“There is a lot of knowledge that you need at the polymer level to make what’s called a spinning solution. And that’s just the chemistry. Then you also have to learn about the operation of the spinning machines. The knowledge of working across disciplines to think about design, chemistry, and engineering all coming together,” she said. “It’s difficult because we don’t have a common vocabulary even though we are often talking about the same things.”

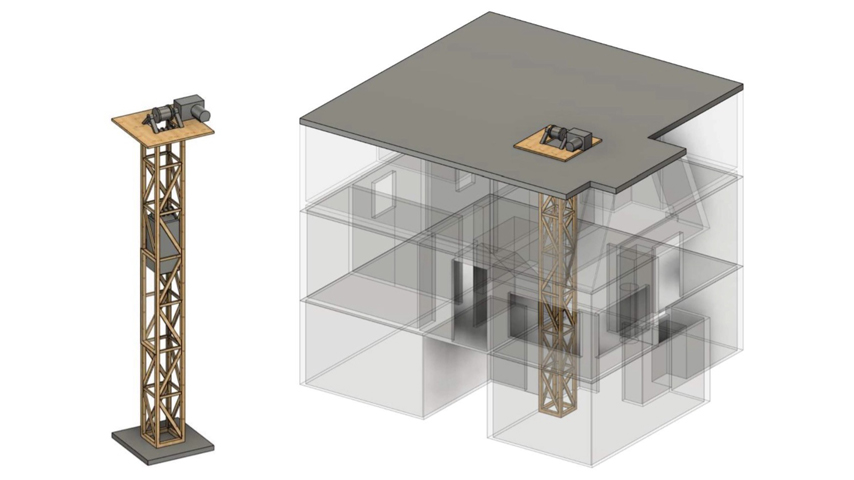

After returning to the ATLAS Institute, Lázaro Vásquez and colleagues, a multi-disciplinary research team, got to work building their own machine. The goal was to build an affordable, desktop-sized spinning machine so that anyone could, in theory, make these fibers. They succeeded. The plans for the machine are open source and available to the public. It costs only $560 to build and produces gelatin-based biofibers that feel somewhat like flax. What’s more, the fibers can be easily dissolved in hot water within an hour once you are done using them.

“Most of the spinning machines for textile making are huge—they take up a whole room. Our machine is exactly the same, every part correlates to the big machine, but it can fit on a desk,” she said. “We imagine our machines being in schools or research labs, the kind of places where people already have been working with 3D printers and other kinds of fabrication tools. They can use these to push the boundaries of new materials and enable prototyping of new types of textiles.”

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

Those who have access to this type of fabrication machine could use the gelatin fibers to create smart textiles. When sensors or electronic components wear out or fail (or the wearer simply grows tired of the garment), they can then recycle the material and move on to a new prototype.

“If you are combining conductive materials like silver or copper threads on a material, to make sensors on a piece of clothing, you can use the gelatin fibers in those textiles,” said Lázaro Vásquez. “That way, when you are done with the item, you can disassemble the sensors and take apart the electronic and non-electronic materials, which can be either reused or recycled separately. The gelatin fibers can then just be dissolved.”

Eventually, Lázaro Vásquez said, she would like to also be able to recycle the gelatin and reuse it for new fibers. She and her colleagues are currently working on new processes to get to that point. In the meantime, she hopes that designers and textile innovators will consider using these novel materials for their designs.

“There’s so much room for exploration and creativity now,” she said. “By putting these new kinds of materials into the hands of people trying to come up with new ideas for biobased fibers into textiles—and other applications beyond textiles—there are all kinds of exciting things that may be coming.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston.

Enter gelatin fibers.

A research team from the University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder) has developed an inexpensive, do-it-yourself machine that can spin textile fibers made from the waste byproducts of the meat industry. Eldy Lázaro Vásquez, a graduate student at CU Boulder’s ATLAS Institute, said while some may look askance at the idea of gelatin—the stuff of JELL-O and grandma’s aspic as the basis for future hoodies and curtains—the biopolymer is well-suited to a variety of textile applications.

“It’s very versatile. I’ve been working with gelatin for years and we’ve made foams out of it, bioplastics out of it, and now we have made these fibers,” she said. “This is a huge waste byproduct of the meat industry. And the ability to use an existing waste stream and develop it into a new sustainable material is a very exciting thing.”

More for You: Lunar Settlements Could Be Made from Fabric

Of course, Lázaro Vásquez admitted, developing the right chemistry to make the right gelatin base for a textile fiber machine was a challenge. She spent a summer at the Institute for Advanced Textiles at Germany’s University of Aachen to learn more about how to successfully make fibers out of bio-based materials. It was there she learned how to take gelatin powder, sourced from the butcher, and prepare it into the right viscous solution that could form a reliable fiber.

“There is a lot of knowledge that you need at the polymer level to make what’s called a spinning solution. And that’s just the chemistry. Then you also have to learn about the operation of the spinning machines. The knowledge of working across disciplines to think about design, chemistry, and engineering all coming together,” she said. “It’s difficult because we don’t have a common vocabulary even though we are often talking about the same things.”

After returning to the ATLAS Institute, Lázaro Vásquez and colleagues, a multi-disciplinary research team, got to work building their own machine. The goal was to build an affordable, desktop-sized spinning machine so that anyone could, in theory, make these fibers. They succeeded. The plans for the machine are open source and available to the public. It costs only $560 to build and produces gelatin-based biofibers that feel somewhat like flax. What’s more, the fibers can be easily dissolved in hot water within an hour once you are done using them.

“Most of the spinning machines for textile making are huge—they take up a whole room. Our machine is exactly the same, every part correlates to the big machine, but it can fit on a desk,” she said. “We imagine our machines being in schools or research labs, the kind of places where people already have been working with 3D printers and other kinds of fabrication tools. They can use these to push the boundaries of new materials and enable prototyping of new types of textiles.”

Discover the Benefits of ASME Membership

Those who have access to this type of fabrication machine could use the gelatin fibers to create smart textiles. When sensors or electronic components wear out or fail (or the wearer simply grows tired of the garment), they can then recycle the material and move on to a new prototype.

“If you are combining conductive materials like silver or copper threads on a material, to make sensors on a piece of clothing, you can use the gelatin fibers in those textiles,” said Lázaro Vásquez. “That way, when you are done with the item, you can disassemble the sensors and take apart the electronic and non-electronic materials, which can be either reused or recycled separately. The gelatin fibers can then just be dissolved.”

Eventually, Lázaro Vásquez said, she would like to also be able to recycle the gelatin and reuse it for new fibers. She and her colleagues are currently working on new processes to get to that point. In the meantime, she hopes that designers and textile innovators will consider using these novel materials for their designs.

“There’s so much room for exploration and creativity now,” she said. “By putting these new kinds of materials into the hands of people trying to come up with new ideas for biobased fibers into textiles—and other applications beyond textiles—there are all kinds of exciting things that may be coming.”

Kayt Sukel is a technology writer and author in Houston.